- Home

- Project Apri sottomenù

- UPLAND ARCHAEOLOGY WORKSHOP Apri sottomenù

-

Abstracts

Apri sottomenù

- Wieke de Neef (Ghent University / Otto-Friedrich University Bamberg)

- Francesco Carrer (School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University (UK))

- Umberto Tecchiati (University of Milan)

- Tesse Stek (KNIR - Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome)

- Riccardo Rao (University of Bergamo)

- Fabio Saggioro, Nicola Mancassola (University of Verona)

- Roberto Maggi, LASA (Laboratorio di Archeologia e Storia Ambientale), University of Genova

- Andrea Cardarelli, Andrea Conte (University of Rome "La Sapienza")

- Federico Zoni (University of Bergamo)

-

Short presentations

Apri sottomenù

- SHORT PRESENTATIONS PROGRAMME

- Putzolu et al., The 2nd Millennium BC in the northern Apennines

- Giorgi et al., New insights into the upland landscape of ancient Epirus, Southern Albania

- Carra, Subsistence economy in the Bronze Age in the northern Apennines upland

- Gaucci et al., Mapping mobility in the Apennines: The Reno Valley between the 6th-4th century BCE and the contemporary period

- Cirelli et al., Insediamenti di altura nell’Appennino Romagnolo e Toscano nel medioevo

- Betori et al., Amatrice: da castello a città

- Del Fattore, Upland landscapes and settlements strategies in the Central-Southern Apennines (1000 BC-2023 AD)

- Conversi et al., The site of Albareto cà Nova

- Bottazzi et al., Attorno al Monte Titano (739 m s.l.m.). Ricerche archeologiche e paleoambientali in Repubblica di San Marino

- Conversi et al., Il sito tardoatico – medievale d’altura della Piana di S. Martino , Pianello Val Tidone (PC)

- Cortesi et al., Archeologia dei paesaggi in una vallata appenninica: il progetto “Val Fantella” (Premilcuore, FC)

- Barbariol, Farms abandonment in Iceland

- Garattoni, Doss Penede (Nago, TN): progettare e costruire un insediamento minore nell’Alto Garda in epoca romana

- Santandrea, Detecting and Mapping Hilltop Sites between the Cesano, Misa, and Nevola River-Valleys

- Bonazzi et al., “Media Valle del Cedrino”: a region between uplands and plateaus

- Zanotti, Back to Monte della Croce

- Monticone et al., Un approccio di archeologia museale al ri-studio del sito neolitico di Chiomonte-La Maddalena (Piemonte, Italia). Revisione ed aggiornamento dei dati dal 1988 al 2023.

- Facciani et al., Exploring the funerary landscape of the Samarkand piedmont area

- Kaur and Poddar, Colonial Churches of Shimla: Public Archaeology as a Tool for Engagement and Outreach

- Datta, Upland Buddhist Monastic Complexes and the Pala Kingdom: Reviewing the Highland-Lowland Relationships in Ancient Bengal

- Staff

- Contacts

- Events calendar

- Seminars Apri sottomenù

- NEWS Apri sottomenù

Del Fattore, Upland landscapes and settlements strategies in the Central-Southern Apennines (1000 BC-2023 AD)

The Jovana Valley (Abruzzo, IT)

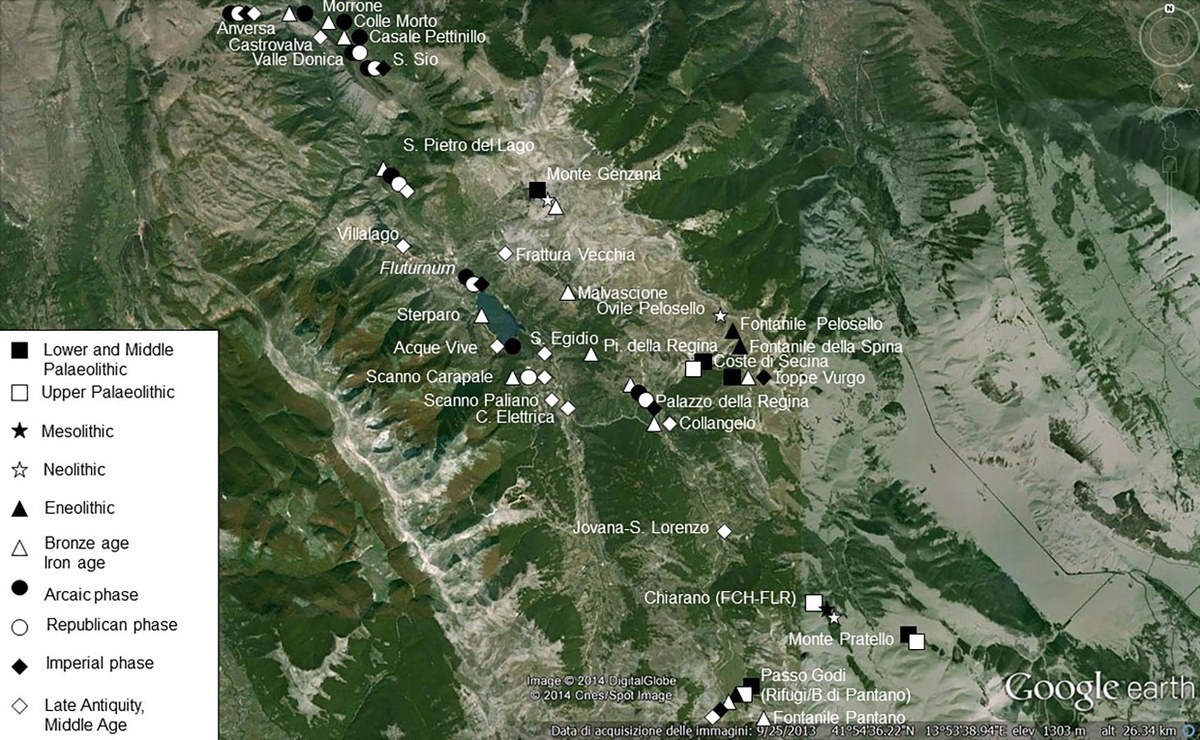

Fig. 1: Scanno (the Province of L'Aquila, Abruzzo) - diachronic archaeological map.

Francesca Romana Del Fattore – Soprintendenza ABAP per le Province di L’Aquila e Teramo. Via di San Basilio 2a, 67100 L’Aquila.

Email: francescaromana.delfattore@cultura.gov.it; cell. +39 338 9116270

Keywords: Apeninnes, Landscapes, Settlements, Pastoralism, Archaeology, Ethnoarchaeology

This work is part of “PECUS” (Pescasseroli Candela Upland Survey), a multidisciplinary research project focused on the droveways’ (tratturi) network in Central and Southern Italy (www.pecus-project.eu). Field data (2010-2016) come from the “Fluturnum Project”, conducted in collaboration with the University of Bologna and aimed at the definition of the archaeological map of the Municipality of Scanno, in the Province of L'Aquila (Abruzzo) (Fig. 1).

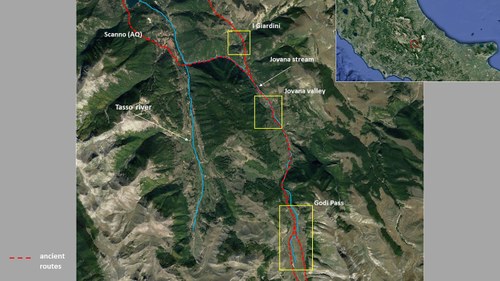

The territory chosen as a sample area is delineated by a seasonal stream locally known as “Jovana”, which gives its name to the homonymous valley. An ancient path, coming up from the Tasso-Sagittarius valley follows the stream, converging into another route, reconstructed for about 20 km during our surveys. Both itineraries connected the Peligna Valley with the Samnium, via the Godi Pass. Surveys have been guided by an anthropological-cultural approach aimed at involving local communities in the recovery of historical, archaeological and traditional evidence. From South to North, along the Jovana stream, three sample areas have been intensely surveyed:

1. Godi Pass 2. Jovana 3. I Giardini (Figg. 2-3).

Godi Pass: an ample upland fluvial plain facing the Sangro Valley towards the South and the Sagittarius/Jovana valleys towards the North. We documented here 45 spot-sample-sites, ranging from mid-upper Palaeolithic up to the Medieval phases, mainly located on the sides of the mountain plain, along which two ancient routes passed. Among our 6 protohistorical spot-sites, the most relevant context is placed on the eastern slope of Godi Mount. Repeated surveys have allowed us to collect abundant impasto materials (Final Bronze Age/early Iron Age). A seasonal settlement, presumably related to pastoral activities: the Godi Pass pastures are still exploited today by several local breeders. Republican and Imperial phases are documented here through 33 spot-sites, showing bronze and ceramic finds, referable to settlement-structures and funerary areas not yet excavated and located along the main routes. We cannot either exclude here the presence of a statio/mansio: Godi pass is located in proximity of the ancient border with the Samnium. Late-antique and medieval finds come from 6 spot-sites, again placed along the ancient routes. Two sheep-pens complexes, still in use, are very well preserved.

Jovana: surveys have revealed here materials referable only to Medieval phases, among which some relevant ceramic fragments of “Archaic maiolica” (13th - 14th century AD). The remains of a late Medieval fortified structure are the most significant evidence. The castrum is located on the top of a hill, in a dominant position over the valley of the Jovana stream. At the foot of the hill, approx. 400 m northward, there are still visible traces of structures – presumably the village – related to the castle. A 16th century chapel documents here the early Christian cult of San Lorenzo, widespread in the area in the Longobard age. Several recent houses – built by recycling ancient materials – are scattered along the valley. A funerary area presumably coeval to the castrum was active along the road that proceeded to the Godi pass, as witnessed by stories of local memory bearers. The scarce materials they collected and preserved are referable to late Medieval phases.

I Giardini: an open, fertile, area located along the southern slope of a hill, exploited until the middle of the last century for agricultural purposes, on artificial terraces. Our surveys have documented protohistoric evidence in two contexts, one of which is located near a spring, not far from an 18th century farmhouse. Impasto sherds are also often scattered on piles of stones accumulated in the recent past at the edges of the fields to clear the ground. A fragmentary statuette representing Hercules and a bronze necklace element were also collected by a local visitor and, although we do not know the precise position of these finds, they testify the frequentation of the area in pre-Roman times. Excavations – between 2013 and 2016 – interested three different sectors of the site, damaged by public works in 1990. A funerary area dating back to the II-I century B.C., was partially excavated.

A second sample excavation brought to light the remains of a building (Republican-Late Imperial phases) situated on an artificial terrace contained by a wall of irregular limestone blocks. Two adjacent rooms were brought to light, one of which – presumably a service structure or an outside area – was paved in opus spicatum.

Fig. 2: The sample areas – location.

The third trench documented three phases of occupation and reuse of a private house (late 3rd - 4th century/6th century A.D., plus a modern phase of re-occupation as a probable pastoral shelter). The archaeobotanical analysis show a highly anthropic rural landscape, where cultivated botanical species (legumes and cereals) were predominant: Vicia faba, Triticum monococcum/dicoccum, and Hordeum vulgare were the most common taxa. Faunal remains consist of caprovines, with a small percentage of cattle and wild species. Currently available data suggest that the site was finally abandoned around the 6th century AD. The area, located in a critical seismic district, may have been affected by different events, such as the earthquakes historically documented between the 4th and the 6th century. We presume that the settlement moved to the top of the naturally defended hill located in front of the site, on whose slopes our surveys have documented late antique ceramic fragments. Remains of medieval-modern buildings are visible on top of the hill, today called “Collangelo”. Numerous recent dry-stone structures correlated to agricultural-pastoral activities are also scattered through the area.

This brief excursus offers a partial diachronic picture of the settlement dynamics – between the end of the Bronze Age and the modern age – and resource exploitation in our sample area. A representative pattern of the complexity that marked the Apennines over the last three thousand years.

Our peripheral mountain territory seems only marginally affected by the climate changes attested in current available Italian pollen diagrams at around 4000 cal. yr. BP and by the profound social and economic events taking place in Central Italy between the 2nd and 1st millennium BC. Small, scattered, settlements are located on hills near the major river (Tasso-Sagittarius) and its tributaries or in the vicinity of permanent water sources, the necropolis along the slopes of the reliefs. Hill-forts, as defensive structures, are placed in correspondence of strategic passages and/or in dominant positions. A dense net of pathways connected the whole territory, forming the basis for a road system definitively organized in historical times.

During the Republican and Imperial phases, we observe a rural landscape organized into agri – open spaces, cultivated or not – vici, pagi, villae or aedificia. A pre-urban territorial organization – typical of the central/southern Apennines – where clusters of houses, small nucleated and scattered settlements or villages (vici), could be part of larger local subdivisions, communities or administrative districts (pagi). We suggest a mixed economy based on agro-pastoral farming. There is some evidence that, since the 1st millennium BC, élite-owned transhumant flocks were an important component of specific central Italic agricultural economies: certainly, transhumance routes are unlikely to leave significant archaeological traces, given their mobility, ephemeral shelters and minimal material culture. However, vertical (or short-distance) transhumance can be inferred from pollen and geochemical analysis. Our sample area, where seasonal pastures are still used nowadays, was served by a road connected to the historical system of pastoral routes that crossed the central-Southern Apennines.

Fig. 3: The sample areas – landscapes.

An increasing number of records shows a complex pattern of climatic changes that affected Roman and late antique societies around the Mediterranean during the first millennium AD. Our current field-work, historical and geo-morphological data suggest here a discontinuous anthropic landscape, as the possible result of this palaeoclimate variability and of the general economic and political situation. We see a widespread reuse of late imperial open settlements (pagi, vici, fundi, aedificia and villae), now belonging to ecclesiae, cellae, casalia and curtes and, in some cases, the occupation or re-occupation of hills and naturally fortified places (as Collangelo). The Norman domination reached our sample district in AD 1140. From the 12th century AD, a systematic encastellation process began in the whole area.

Modern and recent phases (15th - early 20th century) show a considerable anthropic impact, witnessed by the contraction of the woodland cover – evidenced by palynological and sedimentological analyses and by historical documents – even at high altitudes, with clear consequences in terms of erosive phenomena. Only since the mid-twentieth century there has been a new expansion of tree cover, observable through the diachronic reading of remote sensing data and from historical aerial photos. We also have to consider the socio-economic impact of the local dynamic geological activity, still in progress as evidenced by the intense regional seismicity, expressed by major events in 1915, 1984, 2009, 2017. To conclude, some programmatic questions for the future:

- Can the analysis of the exploitation dynamics of a small mountain sample territory help to define adequate strategies to face current climate changes in marginal environments?

- Can the involvement of local communities in recovering the historical memory of their territory be a valid tool aimed at creating a shared awareness, improving dialogue with local public administrations?

- What, then, is the current role of archaeologists, mediators between past and present, in a socio-economic and historical-ecological sense?

REFERENCES

Alessandri L., Schiappelli A., Del Fattore F. R., 2014, Ricerche di superficie nel territorio di Scanno: primi risultati, “Quaderni di Archeologia d’Abruzzo”, 3, pp. 382-387.

Del Fattore F.R., 2016, Fluturnum. Archeologia e Antropologia nell’alta Valle del Sagittario, “Quaderni di Archeologia d’Abruzzo”, 4, pp. 246-248.

Del Fattore et al. 2018 = Del Fattore F.R., Rizzo A., Felici A., From People to Landscapes. Archaeology and Anthropology in the Upper Sagittarius Valley, in Pelisiak A., Novak M., Astaloş C. (a cura di), People and the Mountains – Entering into the New Landscapes, Oxford, 2018, pp. 15-46.

Del Fattore F.R. cds, Il sito archeologico de “I Giardini-Palazzo della Regina” (Scanno, AQ). Campagne di ricerca 2013-2016, “Quaderni di Archeologia d’Abruzzo”, 5, cds.

https://www.fastionline.org/excavation/micro_view.php?item_key=fst_cd&fst_cd=AIAC_3427

https://www.pecus-project.eu/

Highlights

-

The Jovana Valley (Abruzzo, IT)