- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

Any statement on policies designed to shape individuals’ preferences and behaviours will be recorded under this section.

US-2-m

243

ENERGY STAR is a voluntary labeling program designed to identify and promote energy-efficient products to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. No official government regulations tell people that they have to buy ENERGY STAR products, but the substantial growth in the program since 1992 is a testament to the power of motivating people to try to do their part for the environment. In economic language, the moral code of doing one’s part is internalizing externalities. Once you give it some thought, you realize that social enforcement mechanisms are operating all around us and help us take externalities into account.

US-5-m

731-732

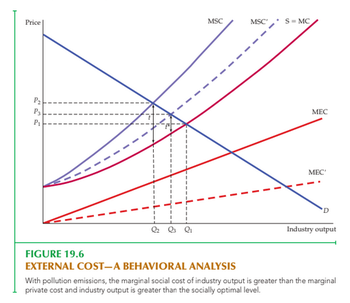

It might well be that if they were properly informed, consumers and firms, on their own and without the incentives of a tax, would reduce their use of fossil fuels. Why might this be the case? Consider the option of replacing incandescent light bulbs with LED bulbs, which are far more energy efficient. [...] While LED bulbs are more expensive than incandescent bulbs, the savings in electricity usage are so large that the LED bulbs will usually pay for themselves in a year or two and thus save money. So, with almost no effort and little or no cost, consumers (and firms) can reduce energy consumption (and thus reduce CO2 emissions by electric power plants). They just need to be properly informed in order to be incentivized to change their light bulbs. Likewise, energy consumption can be reduced if consumers are better informed about the cost savings of better insulation, “smart” thermostats, and so on. This is where behavioral economics comes into play in the design of public policy. If the policy objective is to reduce energy use, we need to understand how people’s behavior affects the decisions they make regarding energy. If consumers were fully rational and utility-maximizing, they would make the effort on their own to learn about the cost savings from LED light bulbs and then act accordingly by switching to LED bulbs. But that’s asking too much of consumers. Instead, one element of public policy would be to educate consumers about LED bulbs, perhaps through paid advertisements or even classes on “home economics and finance” in schools and colleges. The behavioral approach to public policy is illustrated in Figure 19.6 [...]. In this figure, an industry emits a pollutant, so there is a marginal external cost of industry output, given by the curve MEC. The marginal social cost of industry output, MSC, is the sum of the marginal private cost (MC) and the marginal external cost. Industry output is therefore too large: Q1 instead of the socially optimal output Q2. One solution to this problem would be to impose a tax, t, which would equate the marginal social and private costs. But suppose that with a bit of education, consumers and firms would realize that they can save money by reducing their emissions of the pollutant. That would lower the marginal external cost curve (from MEC to MEC’ in the figure) and likewise lower the marginal social cost curve (to MSC’). Output might still be too large (in the figure, Q3 instead of Q2), but a much smaller tax (t* instead of t) would be needed to correct the problem. In the case of CO2 emissions and climate change, there are other ways that consumers and firms might be induced to reduce their energy consumption. One example would be moral persuasion. If consumers were convinced that they have a moral obligation to conserve energy (even if doing so was inconvenient or costly), they might indeed reduce their energy consumption.

732-733

Other policy options might alter (and hopefully improve) the environment in which individuals make choices. For example, one option might be to change the default option available to consumers. In the light bulb example, local ordinances might require stores to make incandescent bulbs available only upon request. Another option might be for stores to be encouraged or even required to feature LED bulbs prominently but to make incandescent bulbs less visible. Finally, stores might be required to simplify consumer choices by displaying signage that clearly describes the advantages of LED bulbs over incandescent bulbs. All of these policy options change the environment in which consumers make choices. Giving consumers a “nudge” in the direction of choices that they would likely make if fully informed can help them to maximize utility.

US-6-m

232

In 2015 the World Bank devoted its annual World Development Report to the topic of behavioral economics, stating that: “Novel policies based on a more accurate understanding of how people actually think and behave have shown great promise, especially for addressing some of the most difficult development challenges, such as […] acting on climate change”.

263

Such policies [flexible working arrangements such as part-time] encourage “time affluence” instead of material affluence. Economist Juliet Schor argues that policies to allow for shorter work hours are also one of the most effective ways to address environmental problems such as climate change. Those who voluntarily decide to work shorter hours will be likely to consume less and thus have a smaller ecological footprint.

389

People’s willingness to pay for environmental attributes may derive from a variety of motivations. Potential reasons for valuing the environment include:

[...]

3. Ecosystem services: tangible benefits obtained freely from nature, as a result of natural processes. Ecosystem services include nutrient recycling, flood protection from wetlands and vegetation, waste assimilation, carbon storage in trees and other plants, water purification, and pollination by bees.

4. Nonuse benefits: nontangible welfare benefits that we obtain from nature. Nonuse benefits include the psychological benefits that people gain just from knowing that natural places exist, even if they will never visit them. The value that people gain from knowing that ecosystems will be available to future generations is another type of nonuse benefit.

451

A growing public awareness and acceptance of the hazards posed by global climate change, for example, could be considered a form of social capital, because it increases the ability of society to respond to a significant threat to its future well-being.

FR-2-m

306

Le jeu du bien public a fait l'objet d'une multitude d'études expérimentales. Parmi les études les plus novatrices, on peut noter celle menée par Manfred Milinski et ses coauteurs à propos de la contribution volontaire au bien public mondial que constitue le climat. Milinski et al. [2006] partent d'un jeu du bien public contextualisé dans lequel la cagnotte permet de financer réellement la publication dans un grand quotidien allemand d'une affiche de sensibilisation aux bonnes pratiques environnementales. Ils observent que leurs sujets participent volontairement au bien public et cela d'autant plus qu'ils sont sensibilisés en amont aux questions climatiques.

Les auteurs proposent un jeu du bien public contextualisé qu'ils qualifient de « jeu du bien public climatique » (climate public goods game). Dans ce jeu, six joueurs doivent choisir simultanément de contribuer 0, 1 ou 2 € à une cagnotte dédiée au climat (climate pool). Les participants savent que le montant final accumulé sur l'ensemble des groupes de sujets servira à financer une affiche de sensibilisation aux enjeux climatiques dans l'un des principaux quotidiens de la ville de Hambourg. Les auteurs étudient en particulier l'impact de deux paramètres : la sensibilisation des sujets aux questions climatiques et la publicité des contributions individuelles. Plus précisément, une partie des sujets lit un texte d'information sur le réchauffement climatique avant de participer au jeu du bien public climatique, les autres n'ayant pas d'information spécifique sur le thème. Par ailleurs, certaines phases du jeu se déroulent en anonymat, les contributions de chaque joueur n'étant pas révélées aux autres, alors que dans les autres phases, les contributions sont rendues publiques. Les auteurs obtiennent trois résultats principaux:

1. les niveaux de contribution moyens sont élevés, en contradiction avec l'hypothèse de passager clandestin;

2. les contributions moyennes son significativement plus élevées lorsque les sujets savent que leurs décisions seront rendues publiques;

3. les contributions moyennes sont plus élevées chez les sujets « informés », c'est-à-dire chez ceux ayant lu le texte d'information, que chez les « non informés ».

L'ensemble de ces résultats donne des indications quant aux initiatives à prendre pour encourager les comportements individuels pro-environnementaux. Ils montrent qu'une majorité de personnes est effectivement prête à contribuer, que la sensibilisation au sujet est un facteur déterminant dans le comportement des gens et que la reconnaissance publique d'une bonne action constitue un facteur incitatif puissant.

a. Milinski M., Semmann D., Krambeck H.-J. et Marotzke J. (2006). "Stabilizing the Earth's climate is not a losing game: Supporting evidence from public goods experiments", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, vol. 103. p. 3994-3908.

FR-4-B

487

Orienter les préférences des agents, notamment par l'information et l'éducation. On peut ici souligner le rôle du Groupe d'experts intergouvernemental sur l'évolution du climat (GIEC). L'ancien vice-président américain A. Gore, à travers le film Une vérité qui dérange (2006) a aussi œuvré dans ce sens. L'information du consommateur passe par un affichage environnemental des produits, facilement identifiable et interprétable. Par ailleurs, de nouvelles méthodes permettent de favoriser des comportements vertueux en matière environnementale. Elles consistent en des « coups de pouce », d'où leur nom de nudges verts, mis en avant notamment par R. Thaler (né en 1945, Prix Nobel 2017) en faveur de comportements éco-vertueux sans recourir à la contrainte. Par exemple, proposer par défaut la démarche la plus écologique (c'est le cas des démarches administratives numériques dans les banques ou pour les impôts). Ces mesures, bien qu'utiles, ne sauraient suffire.