- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E8 : Climate policies

Any statement on policies to mitigate climate change, including debates on the political viability of mitigation. Carbon pricing, behavioural and geoengineering policies are not included.

US-4-m

1044

To address climate change, humans will need to move from a heavy reliance on fossil fuels to using clean energy sources, a process that we, the authors, refer to as the great energy transition. But because so much of the productive capacity of modern economies is dependent upon fossil fuel use, the transition will require economic changes and large-scale investment in clean energy capacity. The adoption of government policies such as taxes, tax credits, subsidies, and mandates, as well as consumer use of smart metering and industrial commitments to clean energy use, are examples of some of the responses that will help bring about the great energy transition. Despite the magnitude of the task, progress has been made: between 2009 and 2016, the cost of solar power fell by 60% and wind power by 40%. In parts of Europe wind power is cost competitive, while in the sunny United States solar power is cost competitive.

US-6-m

145

The authors conclude that attempts to achieve major reductions in gas consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by increasing gas taxes are likely to be ineffective. Instead, they suggest that higher fuel economy standards for new vehicles are likely to be both more effective and more politically acceptable.

387-388

Fossil fuels are subsidized by governments around the world in numerous explicit and implicit ways. Beyond reducing suppliers’ production costs through direct subsidies, implicit subsidies include the failure to institute appropriate Pigovian taxes on fossil fuels for air pollution and climate change damages. According to a comprehensive 2017 journal article, global fossil fuel subsidies were $5.3 trillion in 2015, equal to 6.5 percent of global GDP. About half of total subsidies were attributed to a failure to internalize the externalities associated with local air pollution. Another 22 percent of subsidies were related to global climate change externalities. The analysis found that coal subsidies were larger than oil and natural gas subsidies combined. Among countries, China’s annual subsidy was the largest at nearly $2 trillion, while the United States had the second-largest subsidy, around $0.6 trillion .The authors [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.10.004] conclude that the economic and environmental benefits of eliminating perverse fossil fuel subsidies are significant: The gains for subsidy reform are substantial and diverse: getting energy prices right (i.e., replacing current energy prices with prices fully reflecting supply and environmental costs) would have reduced global carbon emissions in 2013 by 21 percent and fuel-related air pollution deaths by 55 percent, while raising extra revenue of 4 percent of global GDP and raising social welfare by 2.2 percent of global GDP.

404

A similar conclusion was reached by a 2016 analysis which estimated the employment impacts of various potential policies to reduce carbon emissions in the United States. 33 For each policy analyzed, the authors’ model predicted that job losses in “dirty” sectors such as coal mining were essentially offset by job gains in cleaner sectors such as renewable energy. They concluded that the “overall effects on unemployment should not be a substantial factor in the evaluation of environmental policy” because the net effects are likely to be quite small.

427

Transitioning to a low-carbon economy will require investment in energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies.

431-432

Renewable energy currently only provides about 11 percent of the world’s power generation, and fossil fuel power stations last for decades, so it will still take considerable time until we obtain the majority of our energy from renewables. But as detailed in a 2017 paper, a complete global transition to renewable energy by 2050 is economically feasible using existing technologies. The authors conclude that such a transition will avoid about 4.6 million premature air pollution deaths per year, create a net gain of 24 million full-time jobs, save an average of about $85 per person annually in energy costs, and possibly allow the aggressive 1.5 degrees Celsius target to be met. Despite the significant potential for renewable energy, economic policies will make a very large difference in the scale and timing of an energy transition.

520

Also, as societies become more concerned about climate change, there is concern that allowing new low-emission energy technologies to be patented could slow their rates of adoption, as the owner of the patent would produce such technologies based on maximum profit, not social need.

US-7-m

146

Public opinion polls show that a majority of people believe that the government should regulate greenhouse gases. Most economists agree that government policy should attempt to reduce these gases, but they disagree with the public about which government policies would be best. The public tends to support government rules that require firms to use particular methods to reduce pollution—for example, by requiring that automobile companies produce cars with better fuel efficiency. Many economists believe that using these command-and-control policies is a less economically efficient way to reduce pollution than is using market-based policies that rely on economic incentives rather than on administrative rules.

147

Policymakers debate alternative approaches for achieving the goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

164

Although most economists and policymakers agree that emitting carbon dioxide results in a significant negative externality, there is extensive debate over which policies should be adopted for three key reasons. [...] Third, policymakers and economists debate the relative effectiveness of different policies.

US-8-m

253

Another strategy used to confront climate change is to implement incentives to promote resource conservation. The Around the World feature describes a strategy implemented by some cities to reduce traffic gridlock, a major contributor to carbon emissions.

761

Increasing the use of renewable energy can reduce the impact of climate change over time.

762

The ability to minimize climate change requires the ability to meet a greater portion of global energy needs through renewable energy sources.

786

Government failure may result from the practical inability of policymakers to gather enough information to set good policies. Water pollution, for instance, is well understood, resulting in fairly obvious regulatory policies, but the same is not true for issues such as global climate change. Even if we all agree that the Earth is getting warmer and humans are partly to blame, controversy about the adequacy of public policy to address this problem remains.

806

Sustainable development involves a concerted effort by individuals, businesses, and governments to recognize the causes and impacts of climate change and to take appropriate actions. Much of the technology needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is already available today, yet many governments fail to enact policies at the federal level. This has led many state and local governments to pass their own legislation in order to do their part in keeping global warming from worsening.

Examples of governmental social responsibility include supporting bicycle-sharing programs, investing in emissions-free public transportation and light-rail systems, and committing to sustainable procurement practices, such as minimizing unnecessary consumption by reducing, reusing, and recycling products.

806–807

One of the most common methods of reducing greenhouse gases by individuals is through recycling, with some communities even requiring households and businesses to recycle or face fines. Yet, the process of recycling itself uses energy, in addition to labor and other resources. A more effective means of promoting sustainability is to conserve resources. Examples of ways to improve conservation include the following actions:

• Forgo paper financial statements and printed newspapers, magazines, and books-for example, the use of online homework systems and digital textbooks has significantly reduced the use of paper.

• Use LED or compact fluorescent bulbs that use up to 90% less energy than incandescent bulbs (many countries including the United States have phased out incandescent bulbs).

• Install smart temperature controls in homes that automatically reduce air conditioning and heating when the home is empty.

• Plant trees or purchase carbon offsets to fund efforts to plant trees.

• Drive less or drive fuel-efficient or alternative fuel cars (or self-driving cars that reduce traffic congestion).

• Insulate walls and modernize windows.

• Install solar panels.

Clearly, undertaking efforts to reduce our carbon footprint as a nation represents an insurance policy on the future. As new climate change information and technology becomes available, policies can be adjusted to reduce the potential costs in the future.

US-16-m

45

One way that technological progress can contribute to mitigating climate change and biodiversity loss is by reducing the cost of goods and services that are compatible with environmental sustainability. Recent advances in technology have vastly reduced the cost of wind, solar, and other renewable sources of energy.

46

Although democratic governments have been more active in reducing pollution that negatively affects the lives and health of their citizens, they have been reluctant to adopt environmental policies that restrict individual choice— for example, to tax or limit the use of private cars—or that would reduce profits of companies providing carbon-based energy.

47

Climate change and biodiversity loss mean that we need new non-carbon technologies and new policies and institutions to sustain our planet, and at the same time eliminate global poverty.

94

A transition to low-carbon electricity could occur simply by governments ordering it, but it would be more likely to happen—either by government order or by private decisions—if the energy from these sources is cheaper than from fossil fuels. Until well into the twenty-first century, electricity generated from renewables was far more expensive than from fossil fuels. Even in the absence of a carbon tax which will —as intended— raise the price of fossil fuel-based energy, prices have changed dramatically more recently. In most parts of the world, power from new renewable facilities is cheaper than from new fossil fuel ones.

96

The technological progress in renewables is a sign that a path to higher living standards without fossil fuels may be possible. But whether this is feasible on the scale required both to arrest climate change and make a serious dent in global poverty is doubtful.

100

To address the dual challenges of climate change and the elimination of global poverty, changes in the incentives to use fossil fuels along with other public policies are necessary.

159- 160

The Stern Review examined both scientific evidence and economic implications of climate change. Its conclusion, that the benefits of early action would outweigh the costs of neglecting the issue, was reinforced in 2014 by the United Nations Inter governmental Panel on Climate Change (UN IPCC). Early action would mean a significant cut in greenhouse gas emissions, by reducing our consumption of energy-intensive goods, a switch to different energy technologies, reducing the impacts of agriculture and land-use change, and an improvement in the efficiency of current technologies. These changes could not happen under what the Stern Review called ‘business as usual’, in which people, governments, and businesses were free to pursue their own pleasures, politics, and profits, taking little account of their effects on others, including future generations.

212

A number of mechanisms, aided by policy, could accomplish this:

• Governments could stimulate innovation and the diffusion of cleaner technologies: They might do this by, for example, raising the price of goods and services that result in carbon and other emissions, which would discourage their use. In the process, the use of cleaner technologies would become cheaper, lowering the cost of Restrict. For example, renewable energy has become much cheaper. In some regions, it is now the cheapest energy option, which means Restrict is no longer more expensive than BAU. Self-interested behaviour will result in lower carbon emissions.

• A change in norms: Citizens, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and governments can promote a norm of climate protection and sanction or shame countries that do nothing to limit climate change. This would also reduce the attractiveness of BAU.

• Countries can share the costs of Restrict more evenly: This is possible if, for example, a country for whom Restrict is prohibitively expensive instead helps another country where it is less expensive to Restrict. An example would be paying countries in the Amazon basin to conserve the rainforest.

US-2-M

346

Is it possible to maintain long-run growth while averting the effects of climate change? The answer, according to most economists who have studied the issue, is yes. While there will be economic costs, those costs have been falling as technological innovation in clean energy sources advances. The best available estimates show that even a large reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades would cause only a modest reduction in the long-term rise in real GDP per capita. To achieve long-run economic growth with environmental protection, governments will need to use regulations and environmental standards, and institute policies that create market incentives to encourage individuals and firms to make the transition to clean energy sources.

346-347

You may be surprised to learn that taking action against climate change in the United States doesn’t necessarily require new legislation. Under U.S. law, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is obliged to regulate pollutants that endanger public health, and in 2007 the Supreme Court ruled that carbon dioxide emissions meet that criterion. So the EPA initiated a series of steps to limit carbon emissions. First, it set new fuel-efficiency standards to reduce emissions from motor vehicles. Then, it introduced rules limiting emissions from new power plants. Finally, in June 2014 it announced plans to limit emissions from existing power plants. This was a crucial step because coal-burning power plants account for a large part of carbon emissions, both in the United States and in other countries.[...] Still, the EPA’s proposed rules would, at best, make a small dent in the problem of climate change. How much would a program that really deals with the problem cost? In 2014 the United Nations International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that global measures limiting the rise in temperatures to 2 degrees centigrade would impose gradually rising costs, reaching about 5% of output by the year 2100. The impact on the world’s rate of economic growth would, however, be small—a reduction of approximately 0.06 percentage points each year. The IPCC’s numbers were more or less in line with other estimates. Most independent studies have found that environmental protection need not greatly reduce growth. Why this optimism? At a fundamental level, the key insight is that given the right incentives modern economies can find many ways to reduce emissions, ranging from the use of renewable energy sources (which have grown much cheaper) to inducing consumers to choose goods with lower environmental impact. Economic growth and environmental damage don’t have to go together.

347

In order to avert the impact of climate change, effective government intervention is required.

FR-5-M

457

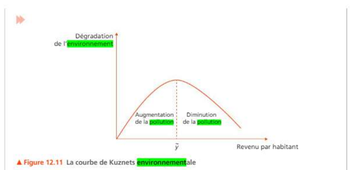

À mesure que le pays se développe, i.e. que la richesse par habitant s'accroît, l'environnement devient une préoccupation de la population, d'autant plus qu'elle prend conscience que les ressources naturelles ne sont que très partiellement renouvelables. Le pays met alors en place des réglementations (taxer les émissions de CO2, par exemple) et/ou développe et adopte des technologies plus vertes. L'environnement est alors considéré comme un « bien supérieur », i.e. dont la demande augmente avec l'accroissement du revenu.

459

Cette prise de conscience de l'épuisement des ressources naturelles et de la dégradation de l'environne- ment à des fins de croissance soulève de nombreuses questions: la croissance est-elle perpétuelle ou son épuisement est-il inéluctable? Faut-il promouvoir la croissance zéro, voire la décroissance? Comment concilier croissance et développement durable? Etc. Prôner la décroissance ou la croissance zéro ne semble pas envisageable mais promouvoir une croissance durable et soutenable (ce que l'on pourrait qualifier de « croissance verte ») est désormais une prise de conscience collective. Les propositions sont nombreuses (taxer les pollutions, favoriser les énergies renouvelables, développer les innovations vertes, etc.) et l'environnement figure désormais comme l'un des objectifs prioritaires des gouvernements ou des groupes de pays (G7, G20, etc.). Reste à franchir le pas!

FR-7-M

53-54

Le système économique actuel pourrait ainsi être porteur de ses propres limites. Sans action concrète, l'épuisement des ressources naturelles et les dégâts causés par le réchauffement climatique risquent de contraindre fortement la croissance de l'activité économique.

Certains économistes, tenant d'une action forte vis-à-vis de la crise climatique, appellent aujourd'hui à mettre en place une «décroissance souhaitée» de l'économie plutôt qu'une « décroissance subie». La stratégie n'est plus alors de réduire les émissions de gaz à effet de serre et la surexploitation des ressources naturelles et d'accepter une baisse de la production en conséquence, mais bien de contraindre l'activité économique afin de réduire ses effets sur l'environnement.

54-55

Un premier pilier serait celui d'une modification de nos habitudes de consommation. Le développement de labels comme celui de l'agriculture biologique ou des immeubles bas-carbone, la mise en place d'incitations notamment pour le recyclage des produits utilisés et le financement de campagne de communication visant à informer les consommateurs vont par exemple dans ce sens. Cette option consiste à faire confiance aux consommateurs-citoyens et à leurs décisions d'achat responsable pour que les entreprises adaptent leurs pratiques et les rendent plus respectueuses de l'environnement.

55

Une quatrième voie est celle de la planification écologique, qui est notamment défendue en France par l'économiste Gaël Giraud. Celle-ci consiste à utiliser des financements publics pour accélérer la transition énergétique et industrielle d'une économie. Il s'agit de faire financer directement par l'État, éventuellement en impliquant le secteur privé, des programmes permettant de réduire les émissions de gaz à effet de serre et de décarboner la production industrielle. Rénovation thermique des bâtiments, construction de nouvelles lignes ferroviaires, déploiement de nouvelles capacités de production d'énergie renouvelable, contribuent à la croissance économique et à l'emploi tout en amenant l'économie sur un sentier de croissance plus respectueux de l'environnement.

156

Cependant, l'apparition de changements climatiques et la disparition d'une grande partie de la biodiversité apparue depuis la seconde moitié du XXème siècle ont amené les responsables politiques et économiques à intégrer à leurs objectifs de développement, le caractère durable de celui-ci. Loin de promouvoir uniquement un développement industriel, rémunérateur mais polluant, il est désormais question de permettre un développement qui respecte l'environnement et les différentes populations.

FR-2-B

150-151

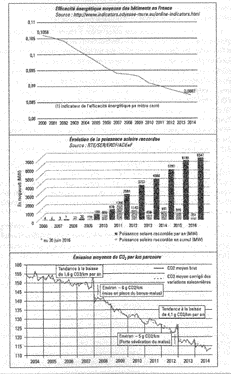

Un «plan bâtiment » a été lancé, comportant des objectifs ambitieux de réduction de la consommation d'énergie et des émissions de GES, respectivement -38% et -50% d'ici 2050. Il passe par des normes d'isolation obligatoires pour les bâtiments neufs et l'attribution de labels comme « Bâtiment basse consommation »(BBC) certifiant les bonnes performances en la matière. Ce sont aussi des instruments de type financier, maniant la carotte des subventions d'une main et le bâton des écotaxes de l'autre. Du côté des subventions, un effort important est fourni pour le développement des énergies renouvelables, en particulier pour favoriser l'installation de panneaux solaires producteurs d'électricité photovoltaïque. EDF s'était engagée à racheter à un bon prix cette électricité, le kilowattheure étant payé trois fois plus cher en 2012 que le tarif de base. Autre exemple, la mise en place d'un système de bonus- malus en 2006 pour les voitures neuves selon l'importance de l'émission en CO2, qui mêle les subventions avec le bonus et la taxation avec le malus.

151

Les effets de ces mesures sont observables à travers la figure 6.6 ci-dessous. On s'aperçoit que l'efficacité énergétique des bâtiments en France diminue, ce qui signifie que l'on réduit les gaspillages en rénovant les bâtiments anciens et en construisant des nouveaux plus économes; que les capacités de production d'électricité solaire ont véritablement explosé en 2009-2010; qu'une diminution sensible des émissions de CO2, des voitures neuves est visible en 2007 et que la baisse est plus rapide depuis cette date.

FR-4-B

488

En outre, un effet pervers peut découler d'une norme limitant la pollution par unité produite ou consommée. En effet, elle peut conduire à un effet- rebond, analysé par S. Jevons dès 1865. La baisse du coût d'utilisation par unité conduit à accroître l'utilisation du bien et à augmenter la pollution. Par exemple, la réglementation européenne limite les émissions des nouvelles voitures à 130 g de CO2, par kilomètre en 2015. Les producteurs limitent alors la consommation en carburant par kilomètre des véhicules pour s'y conformer. Mais les automobilistes sont alors incités à plus emprunter ce mode de transport puisque son coût relatif diminue. De ce fait, la pollution globale augmente.

IN-2-M

46

As a matter of fact, they [developed countries] should not only provide financial assistance to the developing countries for the harm done to the global environment in their growth process in the past but also transfer technology that ensures protection of environment from the growth processes in poor developing countries.