- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

Mentions of mitigation as a social dilemma. This includes climate clubs, free-riding and social dilemmas related to climate change, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

US-1-m

294

Overall, the United States is the second largest emitter of carbon dioxide, accounting for 14 percent of the global total. China is the largest emitter and is responsible for 29 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions.

295

There have been efforts to address greenhouse gases on an international scale. Most notably, the Paris Agreement is a United Nations-brokered agreement that is intended to reduce hazardous emissions worldwide and slow global warming. It was signed by 194 countries and the European Union. As of July 2017, it has been ratified by 153 of those parties. Currently, the United States, under President Trump, is set to withdraw from the agreement though several states have promised that they will still abide by the agreement.

US-2-m

236

Global warming has also been linked to pollutants emitted from power plants. In economic terms, the power plant imposes an externality on the public as a by-product of producing electricity. An externality occurs when an economic activity has either a spillover cost to or a spillover benefit for a bystander. In this case, the plant is imposing a negative externality, because by producing electricity, it creates a spillover cost that it does not consider when making production decisions. Because the owners of the plant do not have to pay for the costs that the plant imposes on society, they do not take into account the health or discomfort of the citizenry in their production decisions. That is, free markets allocate resources in a way that ignores these negative externalities.

251

A much different class of goods appears in the lower-right corner of the exhibit—public goods. Recall that they are goods that are non-rival in consumption and are non-excludable. Consider protecting the earth from climate change.

US-3-m

67

Regularly, at international climate meetings—such as the one in Paris in 2015—government officials, environmentalists, and economists from around the world argue strongly for an increase in the tax on gasoline and other fuels (or, equivalently, on carbon) to retard global warming.

625

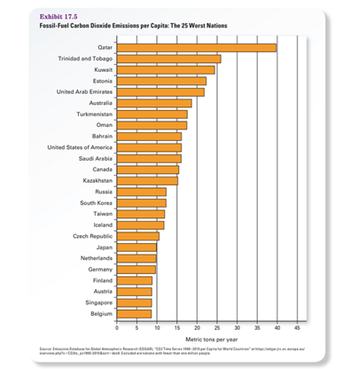

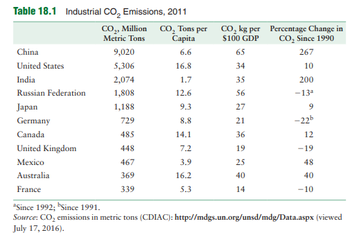

China and the United States are by far the largest producers of CO2 from industrial production, as Table 18.1 shows. The amount of CO2 per person is extremely high in Australia, Canada, Russia, and the United States. China and Russia have a very high pollution to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. The last column of the table shows that China and India at least doubled their production of CO2 since 1990, while only a few countries—such as France, Germany, Russia, and the United Kingdom—reduced their CO2 production. China produces 27% of the world’s CO2, the United States spews out 17%, and India and Russia are each responsible for 5%. Thus, these four countries are responsible for half of the world’s CO2.

626

The one bright spot is that the 195 countries that attended an international meeting on climate change in Paris in 2015 agreed to national goals to restrict emissions. The agreement was ratified in 2016. However, with the election of President Trump, the participation of the United States is in doubt.

US-4-m

1038

Realizing that their citizens are likely to suffer disproportionately more from climate change, poor countries joined forces with rich countries to sign the Paris Agreement in 2015, an agreement between 196 countries to limit their greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid the adverse effects of climate change.

US-6-m

95

Perhaps the greatest externality in human history is the challenge of climate change.

425

The issue of global warming, more accurately described as climate change, has been called “the greatest market failure the world has ever seen.” Developing an adequate policy response to climate change brings together much of our discussion over the last two chapters regarding externalities, environmental issues, and common property resources and public goods.

429

According to most scientists, however, an adequate policy response to climate change will require actions at the international level. Each individual country has very little incentive for reducing its emissions if other countries do not agree to similar reductions. Action to reduce climate change can be regarded as a public good that also generates a positive externality. As we have noted, in the case of public goods, the problem of free riders means that they will not be provided effectively without collective action.

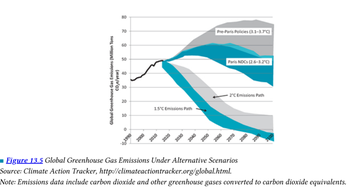

The 2015 Paris climate agreement provides the framework for an international response to climate change. As mentioned above, the goal of the agreement is to limit eventual warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, or even better to below 1.5 degrees Celsius. Rather than imposing universal climate policy mechanisms, such as a global carbon tax, or legally binding emissions targets, the Paris agreement is built upon voluntary “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs). Each participating country is free to set its own emissions targets, with some targets being relatively ambitious while others are comparatively modest. For example, Costa Rica has set strong interim targets along a path to become fully carbon neutral (no net carbon emissions) by 2085. Other countries’ NDCs have been rated “critically insufficient” by the nonprofit organization Climate Action Tracker, including Russia, Chile, and Saudi Arabia.

As of late 2018, a total of 174 countries have submitted their NDCs to the United Nations. While the United States signed the Paris agreement in 2015, in June 2017 President Donald Trump announced that the country was withdrawing from the treaty, although under the terms of the agreement it cannot officially withdraw until 2020. Despite the lack of current policy action on climate change at the federal level in the United States, numerous states and municipalities continue to pursue aggressive policies. A group of at least 20 states and 50 major cities have pledged to continue efforts to meet the country’s Paris climate targets.

Each country is free to set its own national policies to meet its NDC, and there are no penalties for countries that fail to meet their targets. Still, the Paris agreement represents the most comprehensive international climate framework so far; the 1997 Kyoto Protocol only included developed nations. The agreement calls for developed nations to contribute $100 billion per year to help developing countries transition away from fossil fuels and adapt to the impacts of climate change. Every five years participating countries will meet to reevaluate their NDCs, with the intention of setting more ambitious targets to reflect each country’s “highest possible ambition.”

More ambitious NDCs will be needed in order to meet the objective of limiting eventual warming to 2 degrees Celsius or less, as shown in Figure 13.5. Prior to the Paris agreement, under existing national policies global greenhouse gas emissions were projected to continue to increase until at least 2050 and potentially until 2090 (the top gray-shaded range of emissions), with an expected global temperature increase between 3.1 and 3.7 degrees Celsius. If all countries meet their Paris NDCs, then global emissions will peak sooner, and will be between 39 percent lower and 6 percent higher than current emissions in 2100 (the higher blue-shaded range of emissions). But the global average temperature will still increase between 2.6 and 3.2 degrees Celsius if all countries meet their NDCs. We see that in order to meet the 2 degrees Celsius target, global emissions will need to begin to decline essentially immediately, and be between 80 percent and 106 percent lower than current emissions in 2100. (Negative net emissions are possible if large amounts of carbon are removed from the atmosphere through expansion of forests or other methods.) Even more dramatic emissions reductions are necessary to achieve the 1.5 degree Celsius target, as shown by the bottom blue-shaded emissions range.

US-7-m

148

When you buy a Big Mac, the price you pay covers all of the cost McDonald’s incurs in producing the Big Mac. When you buy electricity from a utility that burns coal and generates carbon dioxide, though, the price you pay covers some of the costs the utility incurs but does not cover the cost of the damage carbon dioxide does to the environment. […]There is a negative externality in the generation of electricity.

164

Second, carbon dioxide emissions are a worldwide problem; sharp reductions in carbon dioxide emissions only in the United States and Europe, for instance, would not be enough to stop global warming. But coordinating policy across countries has proven difficult.

In 2015, representatives from 195 nations meeting in Paris agreed to voluntary efforts to restrict emissions of greenhouse gases. The same year, the Obama administration introduced the Clean Power Plan, which would have required states to reduce power plant emissions to 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. In 2017, though, the Trump administration decided to withdraw from the Paris agreement and cancel the Clean Power Plan regulations. Some members of the Trump administration argued that the Clean Power Plan’s goals would be difficult to meet without disrupting the country’s power supply.

US-8-m

253

Every person on the planet is affected by changes in our climate, which have become more apparent in recent years. Efforts to combat climate change can be viewed as a large public good-everybody benefits without rivalry or exclusion. Therefore, climate change policy illustrates a market failure because the actions that protect against climate change are costly, but the benefits of such actions are enjoyed by all Earthlings, including those who do not pay (known as free riders). This is a common problem inherent with public goods.

Moreover, actions that affect climate change exhibit externalities. The amount of carbon emissions emitted by countries vary significantly. If one country pollutes more due to greater industrialization, an external cost is generated on the rest of the world. On the other hand, countries that promote sustainable production generate external benefits. Clearly, some countries do more to combat climate change than others, which illustrates the challenges of mitigating the issue. While nearly everyone desires a cleaner planet, not everyone wishes to pay to achieve that goal.

Governments have come together to address climate change by forming agreements to combat the problem in an equitable manner. One recent example is the Paris Agreement, which was signed by nearly every country in the world, including the United States, in 2016. But because opinions change, in 2017 the United States announced its intent to pull out of the Paris Agreement. Although official U.S. government policy may take one position, many American individuals and firms remain strong proponents of reducing climate change, with many corporations taking the lead in reducing their carbon footprint.

255

Much like climate change policy, health care policy generates many external benefits and external costs.

256

Climate change, health care, and education are important issues facing societies that involve debate of how to resolve market failures.

264

Ecological conservation is a public good. Once people devote time and resources to reducing climate change, everybody benefits from it, even if one does not contribute to the costs.

758

Because of differing environmental priorities among nations, it is difficult to achieve a consensus. In addition, any one country's efforts to improve the environment benefit the entire world, yet that country bears the full costs of these efforts. Meanwhile, other countries may exploit the environment for their economic gain, offsetting the environmental efforts made by others.

759

A challenge to mitigating global climate change is that markets do not always lead to a socially optimal allocation of resources. When competing self-interests by individuals and firms interact in a market, efforts to achieve a common goal on climate change become difficult.

802-803

To further compound the problem, global climate change is a public good. Nobody can have less of it when someone has more (non rivalry), and nobody can be excluded from its negative effects (non excludability). Technical innovations that help reduce CO2 emissions are costly to develop and are difficult to profit from due to the free rider problem, which means that efforts to combat climate change need to involve governments or organizations wishing to fix the problem for the greater good.

805

Globally, there has been increased effort in recent years to combat climate change, especially in the United States and China, the two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. In 2016, nearly every country in the world signed the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse emissions by setting targets (a nationally determined contribution) that would lead to a collective worldwide effort to keep the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels. The agreement requires signing nations to reconvene every five years to report their progress, essentially creating global peer pressure to achieve its goals.

Despite the promising progress, issues of equity arise when combating global warming. Why should one country invest in expensive clean energy processes when its neighbor countries choose a less expensive approach? Such issues can become very political quickly. In 2017, the Trump administration announced that the United States would withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Yet, the United States continues to meet its targets from the Paris Agreement due to market forces demanding cleaner energy and an increased urgency by local and state governments, corporations, and individuals to take action. In fact, efforts to promote sustainable development have increasingly become part of political platforms, corporate sustainability missions, and individual environmental awareness.

807

The public goods aspects of climate change make it a truly global problem.

812

Global climate change is a huge global negative externality accompanied by public goods aspects and extremely long time horizons, making the inherent market failure difficult to address.

US-9-m

203

The problem of climate change is especially difficult to solve because the external cost of carbon emissions crosses all borders and boundaries.

US-10-m

239

Cap and trade is a good idea, but there are issues that must be overcome to make it work effectively. For example, cap and trade presumes that nations can agree on and enforce emissions limits, but international agreements have proved difficult to negotiate. Without binding international agreements, nations that adopt cap and trade policies will experience higher production costs, while nations that ignore them - and free-ride in the process - will benefit.

US-11-m

355

As we continue our examination of market failure, we look first at externalities as a source of inefficiency. When you buy a car or decide how much to drive it, how much do you consider the effects on the environment of the carbon produced by that car?

365

The Economics in Practice box on the next page describes the Paris Agreement, which requires countries to pledge their commitment to improve their environmental impact.

366

In 2015, representatives of 196 nations, intragovernmental agencies, and business organizations came together the Paris Agreement to draw long-term goals for adaptation and agreed to adopt a set of policies to mitigate the impact of climate change. Under the Paris Agreement, governments will prepare nationally determined contributions (NDCs). NDCs outline a country’s targets to reduce national emissions to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius and the steps it has taken to address climate change. As of mid-2018, 18 countries have submitted their NDCs, accounting for 56 percent of global GHG emissions.

459

Nevertheless, the concern with global climate change has stimulated new thinking in this area. A study by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in Britain found that in 2004, 23 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by China were created in the production of exports. In other words, these emissions come not as a result of goods that China’s population is enjoying as its income rises, but as a consequence of the consumption of the United States and Europe, where most of these goods are going. In a world in which the effects of carbon emissions are global and all countries are not willing to sign binding global agreements to control emissions, trade with China may be a way for developed nations to avoid their commitments to pollution reduction. Some have argued that penalties could be imposed on high-polluting products produced in countries that have not signed international climate control treaties as a way to ensure that the prices of goods imported this way reflect the harm that those products cause the environment. Implementing these policies is, however, likely to be complex, and some have argued that it is a mistake to bundle trade and environmental issues. As with other areas covered in this book, there is still disagreement among economists as to the right answer.

US-12-m

198

Last year, Donald Trump pulled the United States out of the Paris agreement on greenhouse gas emissions.

US-16-m

46

Climate change, and the conservation of oceans and some rivers, requires not only individual government action, but international agreement.

160

But national governments disagree on which policies to adopt, and who should bear the costs. Countries’ interests differ according to their stage of economic development, possession and use of natural resources, and vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. The 2015 Paris Agreement made progress: countries would adopt domestic mitigation measures to achieve ‘nationally determined contributions’ to emissions reduction, with the goal of limiting the temperature rise to 1.5°C by the end of the century and avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.

[...]

The problem of climate change is extreme, but far from unique. It is an example of a social dilemma. Social dilemmas occur when people do not take adequate account of the effects of their actions on others, whether these are positive or negative.

[...]

Humanity would be better off emitting less pollution, but if you as an individual decide to cut your consumption or your carbon footprint, you will hardly affect the global levels.

161

Altruistic motivations can help to address social dilemmas—because our altruism means that we care about how our actions affect others—but for global challenges like climate change, altruism will not be sufficient: new government policies will have to be involved.

162

For example, one person’s choice of how much to heat their home will affect everyone’s experience of global climate change.

190

When people engage in a common project—whether pest control, irrigation, or reducing carbon emissions—everyone has something to gain if they cooperate, but also something to lose when others free-ride.

208

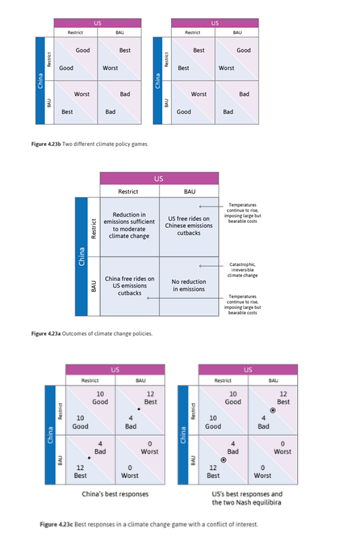

Reducing carbon emissions requires much greater changes, across many industries and affecting all members of society. One of the obstacles at the United Nations’ annual climate change negotiations has been disagreement over how to share the costs and benefits of limiting emissions between countries—and in recent years, the heavy costs some countries now face from the effects of past emissions elsewhere. To explore the possible situations facing climate negotiators, we will model them as a game between two large countries, hypothetically labelled China and the US, each considered as if it were a single individual. First, we identify possible equilibria when each country behaves strategically; then we can think about how an agreed outcome might be achieved.

209

Figure 4.23a shows the outcomes of two alternative strategies: Restrict (taking measures to reduce emissions, for example by regulating or taxing the use of fossil fuels) and BAU (continuing with ‘business as usual’). What we can expect to happen depends on the pay-offs in each outcome. The essential features of the problem can be captured using an ordinal scale from Best to Worst: it is the order of the pay-offs, not the size, that matters. Figure 4.23b shows two games, corresponding to different sets of hypothetical pay-offs.

210

If you work out the best responses and find the Nash equilibria in each case, you will realise that these two games are similar to cases we have already analysed. The left-hand one is a prisoners’ dilemma, in which BAU is a dominant strategy for each country, leading to a Bad outcome for both. The game on the right is a coordination game, [...] except that the players would like to coordinate on the same strategy, rather than the opposite one. There are two Nash equilibria: one is the Best outcome, in which both countries restrict emissions. But the Bad outcome in which neither do so is also an equilibrium, and if each country expects the other to choose BAU following their past behaviour, we can predict that they may be stuck in the (BAU, BAU) equilibrium. In each case, negotiation may be able to improve the outcome.

[...]

Figure 4.23c presents a third model. It also shows the players’ best responses, and hypothetical numerical pay-offs indicating the value of each possible outcome to the citizens of each country. The worst outcome for both countries is that both persist with BAU, thereby running a significant risk of human (and many other species’) extinction. The best for each is to continue with BAU and let the other one Restrict. The only way to moderate climate change significantly is for both to Restrict. This is another coordination game with two equilibria, but now [...] there is a conflict of interest between the players. This game is what is termed a hawk–dove game: players can act like an aggressive and selfish Hawk, or a peaceful and sharing Dove. In the climate change version, Doves Restrict and Hawks continue with BAU. The conflict of interest is that each country does better if it plays Hawk while the other plays Dove. It captures a situation that is different from the previous two. Both countries have incentives to avoid catastrophic climate change. But they strongly prefer that the other should bear the costs of reducing emissions: each would like to wait to determine if the other will move first.

211

The Pareto-efficient allocation in which both countries restrict emissions also has the highest joint pay-offs. We can think of this as the best outcome for the world as a whole. But it is not an equilibrium.

Applying the hawk–dove game to climate policy

How do you think the hawk–dove game would be played in reality? Can the conflict of interest be resolved? If one country could commit itself to BAU so that the other was certain that it would not consider any other strategy, then the other would play Restrict to avoid catastrophe. But this is true for both countries. Negotiations are bound to be difficult, since each country would prefer the other to take the lead on restricting carbon emissions. The real climate negotiations are of course more complex—virtually all countries in the world are involved. Pay-offs may be different for these varied players. For example, in 2021 China produced 31% of the world’s total carbon emissions, the US was second with 44% of China’s level, followed by India. On a per-capita basis, China produced 55% of the emissions that the US did, and India produced 13% of US emissions.

211-212

How could the global social dilemma of climate change policy, as represented in this game, be solved? Could the governments of the world simply prohibit or severely limit emissions that contribute to the problem of climate change? This would amount to changing the game by altering available strategies by making BAU illegal. But who would enforce this law? There is no world government that could take a government that violated the law to court (and lock up its head of state!). If the climate change social dilemma is to be addressed, Restrict must be in the interests of each of the parties. Consider the bottom-left corner (China plays BAU, US plays Restrict) equilibrium. If the pay-offs to China for playing Restrict were higher, when that is what the US is doing, then (Restrict, Restrict) might become an equilibrium. Indeed, in the eyes of many climate change scientists and concerned citizens, the aim of global environmental policy is to change the game so that (Restrict, Restrict) becomes a Nash equilibrium.

212

Following the 2015 Paris Agreement, almost all countries submitted individual plans for cutting emissions. Although there is no way that the agreement could be enforced, and these plans are not yet consistent with the goal of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5°C, it is widely considered as a basis for further international cooperation. The Paris Agreement should:

• allow countries to better understand the costs of restricting emissions

• encourage economic players to innovate in order to further lower the costs

• strengthen norms that reduce the attractiveness of BAU

• establish a base of trust to share some of the costs of Restrict and negotiate more ambitiously in the future.

213

Addressing the challenge of climate change requires understanding conflicting as well as common interests.

214

Game theory—including the hawk–dove game—provides alternative ways of representing the challenge of climate change, and means of addressing it.

504

People throughout the world make decisions resulting in carbon dioxide emissions without considering how their decisions contribute to climate damage.

505

The price of fossil fuels typically reflects the suppliers’ costs of extracting and distributing them, but not the costs of global warming which affect all of us.

525

A country that invests in reducing carbon emissions lowers the risks of climate change for other countries.

527

If one farmer contributes to the cost of an irrigation scheme, or one country takes measures to reduce carbon emissions, all farmers or all countries benefit. The irrigation scheme is a public good for the community where it is located. Reductions in atmospheric CO2 are a global public good.

532

We can define public bads: air pollution, for example, is a bad that affects many people simultaneously. It is non-rival in the sense that one person suffering its effects does not reduce the suffering of the others. Atmospheric CO2 is a global public bad.

US-2-M

344

However, tackling climate change—a problem of global environmental degradation—has been a much harder problem to solve because policies must be implemented on a global scale, requiring the cooperation of many countries.

345

In 2015, in acknowledgement of the seriousness of the problem, 196 countries came together under the Paris Agreement, committing to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases in an effort to limit the rise in the earth’s temperature to no more than 2 degrees centigrade. The linchpin of the agreement was cooperation between China, India, and the United States. China and India agreed to limit their emissions, and the United States, along with other rich countries, committed to develop various forms of public and private financing to help poorer countries pay the cost.

Under the Paris Agreement of 2015, 196 countries agreed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to limit the rise in the earth’s temperature to no more than 2 degrees centigrade.

346

Finally, governments—both rich and poor—will need to continue to cooperate with one another. Getting political consensus around the necessary policies will be key.

347

In the Paris Agreement of 2015, 196 countries agreed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to limit the rise in the earth’s temperature.

US-8-M

340

Much of the increased carbon emitted by Chinese businesses, for example, is associated with goods that are transported and traded to Europe and the United States. These consumers thus share the benefits of this air pollution through the cheaper goods they consume.

380

Nevertheless, the concern with global climate change has stimulated new thinking in this area. A study by the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in Britain found that in 2004, 23 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by China were created in the production of exports. In other words, these emissions come not as a result of goods that China’s population is enjoying as its income rises, but as a consequence of the consumption of the United States and Europe, where most of these goods are going. In a world in which the effects of carbon emissions are global and all countries are not willing to sign binding global agreements to control emissions, trade with China may be a way for developed nations to avoid their commitments to pollution reduction. Some have argued that penalties could be imposed on high-polluting products produced in countries that have not signed international climate control treaties as a way to ensure that the prices of goods imported this way reflect the harm that those products cause the environment. Implementing these policies is, however, likely to be complex, and some have argued that it is a mistake to bundle trade and environmental issues. As with other areas covered in this book, there is still disagreement among economists as to the right answer.

FR-2-m

302

Le climat est considéré comme le bien public mondial par excellence. D'une certaine manière, la lutte contre le réchauffement climatique consiste à organiser de manière politique et économique la gestion de ce bien public mondial.

304

Dans le cas des biens publics mondiaux, le problème du passager clandestin est encore plus sévère. Concernant la lutte contre le réchauffement climatique, il est de l'intérêt de chaque pays de se désolidariser de l'effort commun tout en espérant bénéficier des résultats provenant des efforts des autres. Comme le note Nordhaus [2015], c'est bien ce problème du passager clandestin qui explique la défaillance du protocole de Kyoto, avec notamment la non-adhésion des États-Unis et de la Chine, deux passagers clandestins particulièrement « lourds ». Sur ce problème très spécifique du climat, la solution passe par l'invention d'une nouvelle forme de gouvernance au niveau mondial qui permette d'éliminer les incitations à la stratégie du passager clandestin. L'Encadré [ci-dessous] présente la proposition récente de William Nordhaus, fondée sur le concept de « club climatique »

LES CLUBS CLIMATIQUES (NORDHAUS [2015]")

Pour sortir du problème fondamental du passager clandestin dans la politique climatique internationale, Nordhaus propose un dispositif de club climatique formalisant un accord des pays membres à réduire leurs émissions de polluants. Plus précisément, il s'agit de fixer une cible commune pour un prix du carbone minimum à atteindre par chaque pays en utilisant les instruments de son choix (taxe, marché de permis, système hybride, etc.). Le point décisif par rapport au probleme du passager clandestin est de rendre la non-adhésion au club trop couteuse pour inciter un pays à faire cavalier seul. A ce niveau-là, l'idée de Nordhaus est de coupler la politique climatique à la politique commerciale en envisageant des représailles commerciales sous la forme de tarifs douaniers sur les importations des pays non adhérents. Le point fort de cette proposition est la pénalité liée à la non-participation au club : cela conduit à une situation dans laquelle, en raison de la structure même des incitations, il devient de l'intérêt de chaque pays d'adhérer au club et de mettre en place un programme de réduction des émissions. Nordhaus fait des propositions concrètes quant à l'organisation et au fonctionnement d'un tel club climatique.

a. Nordhaus W. (2015). "Climate Clubs: Overcoming Free-riding in International Climate Policy", American Economic Review, vol. 105, p. 1339-1370.

313

Il est clair que le réchauffement climatique apparaît comme le cas ultime de tragédie des communs, le climat étant un bien public mondial, la ressource commune concernée la terre dans son ensemble, et l'enjeu la survie de l'espèce ! Comme l'ont noté Milinski et al. [2006] ou Pfeiffer et Nowak [2006], il s'agit du plus important « jeu du bien public » joué par les humains, un jeu à plus de six milliards de joueurs, « que l'on ne peut pas se permettre de perdre ».

FR-4-M

308

Il est bien connu que les marchés fonctionnent mal en présence d'externalités. En ce qui concerne la croissance économique, l'une des principales externalités est l'émission de gaz à effet de serre. Le coût de ces émissions n'est pas pris en compte par les entreprises et les ménages lorsqu'ils prennent leurs décisions, par exemple en choisissant une technologie plutôt qu'une autre, ou en achetant une voiture.

311

Les négociations internationales sur le climat sont source de tensions importantes entre les marchés émergents et les économies avancées. [...] Plus généralement, il est difficile de trouver un accord entre l'ensemble des pays, ce que montre le succès limité des conférences sur le climat.

FR-7-M

17

Le coût pour la société des émissions de gaz à effet de serre n'est ainsi pas comptabilisé, alors que celles-ci coûtent cher à la planète en contribuant au réchauffement climatique. Le fait qu'un pays pollue beaucoup, ou tire sa richesse de l'extraction de ressources naturelles non-renouvelables, ne sera pas comptabilisé dans le PIB.

FR-2-B

148-149

Le développement durable implique une concertation internationale pour agir efficacement, et c'est particulièrement le cas en ce qui concerne le changement climatique puisque ses causes, l'émission des GES étant la principale, comme ses conséquences, telles que la montée du niveau des océans, sont mondiales.

C'est ainsi que des sommets internationaux ont rythmé l'avancée sur le chemin du développement durable depuis les années 1980 - par exemple celui de 1987, qui a été marqué par la publication du rapport Brundtland. C'est lors du premier « Sommet de la Terre » en 1992 qu'une prise de conscience a véritablement émergé au niveau international quant aux dangers du réchauffement climatique. Elle a été favorisée par les travaux du Giec (Groupement intergouvernemental d'experts sur le climat), créé en 1988 afin d'établir un diagnostic fiable et neutre sur la question. Le sommet de Rio 1992 a établi un principe dit « de responsabilité commune différenciée » qui établit que tous les pays de la planète doivent s'impliquer, mais différemment selon leurs moyens. Ce souci d'équité, constitutif du développement durable, implique que les efforts doivent dépendre du niveau de développement. Le résultat en a été le protocole de Kyoto, décidé en 1997, qui a créé des engagements contraignants pour les seuls pays les plus développés, validant l'idée que les pays du Nord doivent agir prioritairement et solidairement des pays du Sud.

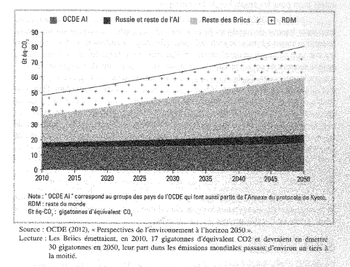

Ces beaux principes ont toutefois débouché sur une réalisation limitée, les espoirs ayant été vite déçus par le retrait des États-Unis du protocole de Kyoto, leur président de l'époque, George Bush Sr., déclarant très explicitement alors que « le mode de vie américain n'est pas négociable ». Cela a beaucoup restreint la portée du protocole de Kyoto, qui n'a jamais régulé que 40 % des émissions mondiales de GES, part tombée même à 17 % en 2010, car entretemps les pays émergents sont devenus les plus gros émetteurs de GES, la Chine en tête. C'est ce que montre la figure 6.5, qui prolonge cette tendance jusqu'en 2050.

149 -150

On est longtemps allé d'échec en échec lors des grandes réunions internationales sur ce thème, la conclusion du sommet de Copenhague de 2009 étant particulièrement décevante et celle de Rio+20 en 2012 tout aussi médiocre. En fait, c'est toute la difficulté de parvenir à s'entendre au niveau international qui est illustrée par la lenteur des progrès réalisés dans la lutte contre le réchauffement climatique. Ces négociations internationales sont le lieu d'affrontements entre les pays, en particulier entre le Nord et le Sud. Les pays en développement sont réticents à agir, arguant le fait que les pays anciennement industrialisés ont une « dette écologique » puisque les 4/5 des GES accumulés dans l'atmosphère sont le legs de leur développement économique depuis la révolution industrielle. Les pays non développés ont beau jeu de les renvoyer à leur responsabilité passée et de refuser de porter un poids que les pays développés n'ont pas eu à subir au cours de leur propre histoire. D'autant plus qu'ils soupçonnent que le Nord utilise le prétexte environnemental pour pratiquer un protectionnisme déguisé vis-à-vis d'eux. Friedrich List, économiste allemand du XIX siècle, dénonçait déjà à son époque des pratiques protectionnistes consistant, pour les puissances dominantes, sous de mauvais prétextes, à «tirer l'échelle » aux autres pays pour les empêcher de les rattraper.

Mais la COP21 qui s'est tenue à Paris à la fin de l'année 2015 a semblé rompre avec cette logique de paralysie. Réunissant 195 pays, elle a débouché sur un accord historique visant à limiter le réchauffement climatique à seulement +1,5°C et à financer une aide aux pays en développement d'au minimum 100 milliards de $ par an. Ce qui est au cœur de cet accord de Paris est surtout l'engagement de renégocier régulièrement les montants d'aide et les objectifs de contributions à la réduction d'émission de GES fixés par chaque pays. Même si pour l'instant, ces efforts sont loin d'être suffisants, il y a un pari sur le renforcement de la discipline que les États vont s'imposer dans cette lutte contre le changement climatique. C'est un pari sur l'avenir qui repose plus sur l'espoir des effets de l'émulation entre États et de la prise de conscience de la nécessité de leur action que sur des mécanismes de sanction qui sont absents de l'Accord de Paris. Mais, on peut avoir aussi une vision plus pessimiste en pointant la fragilité de son efficacité puisque rien n'empêche les défections des États et les retours en arrière dans les efforts consentis. Le discours de Donald Trump, élu en 2016 nouveau président des États-Unis, n'est pas très encourageant de ce point de vue.

La réussite de la COP21, malgré les vicissitudes dont risque d'être victime sa mise en œuvre, est toutefois le signe clair d'une préoccupation croissante pour le développement durable partout dans le monde.

FR-3-B

93

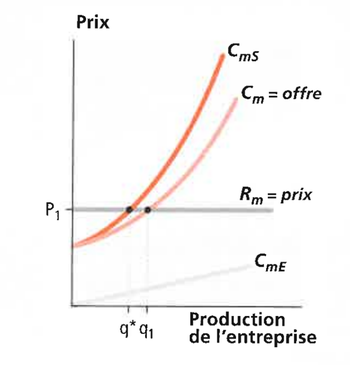

[Les caractères 1 et m sont originellement en indice dans P1,q1, CmS, Cm]

Une externalité est la conséquence d'une action d'un agent (produire, consommer, etc.) sur un autre agent, sans que cette conséquence ne transite par le système des prix. La production d'électricité par une centrale à charbon, par exemple, entraîne une pollution liée à l'émission importante de CO2, qui pénalise toute la population avoisinante : c'est une externalité négative. Parce que le marché ou le système des prix ne prend pas en compte les externalités, cela peut conduire à des défaillances de marché.

Reprenons l'exemple de la centrale électrique à charbon. L'entreprise étant en situation de concurrence, elle est price taker et le prix de l'électricité s'impose à elle. Ce prix P1 est donc aussi la recette moyenne et marginale. L'optimum privé du producteur est atteint quand le coût marginal est égal à la recette marginale. Cela correspond au point d'intersection d'une quantité q1, à un prix P1, sur le graphique. Cet optimum privé correspond-il à l'optimum social ? La production d'électricité par ce type de centrale conduit à émettre des émissions importantes de CO2, qui pénalisent l'ensemble des riverains sans que cette nuisance soit facturée à l'entreprise (elle n'est pas intégrée dans sa courbe de coût). La courbe de coût marginal externe (CmE) représente justement la nuisance sur les riverains liée à la production d'une unité supplémentaire d'électricité. Elle est croissante dans la mesure où le préjudice croît plus rapidement que les quantités émises. La courbe de coût marginal social (CmS) est donc la somme du coût marginal de l'entreprise plus celle des riverains: CmS = Cm + CmE. On constate qu'au niveau de prix P1, l'optimum social n'est pas q, mais q*: en d'autres termes, en situation d'externalités négatives, la firme a tendance à surproduire par rapport à l'optimum social.

FR-4-B

496-498

Les accords multilatéraux sur l'environnement (AME) jouent un rôle essentiel. Ils visent à protéger et à restaurer l'environnement mondial dans des domaines tels que l'air, le vivant, les milieux marins, les déchets dangereux, etc. et à contribuer au développement durable. […] L'un de ces accords, la Convention cadre sur le changement climatique (1992) comprend des textes importants tels que :

- la déclaration sur l'environnement et le développement;

- la déclaration sur les forêts;

- la convention sur le changement climatique;

- la convention sur la biodiversité.

En 1997, dans le prolongement du Sommet de la Terre, la conférence de Kyoto adopte un accord en vue de réduire les émissions de CO2. Sous la pression de l'Europe, les États-Unis acceptent le principe de limitations quantitatives à travers le marché de quotas d'émission. Il est admis à cette occasion qu'il appartient aux pays industrialisés de faire l'effort principal de réduction de leurs émissions. Mais cet accord est remis en cause après la victoire de G. Bush aux élections présidentielles de 2000 aux États- Unis.

[…]

Il est nécessaire également de mieux articuler régulations commerciales (OMC) et environnementales. À ce titre, la proposition de W. Nordhaus est de mettre en place un droit de douane uniforme, d'un montant limité, imposé par un club de pays s'engageant sur un objectif contraignant et ambitieux, sur des produits en provenance de pays ne participant pas à l'accord. Un organisme de supervision serait utile. Certains plaident pour une Organisation Mondiale de l'Environnement.

[…] On est face à un dilemme du prisonnier des politiques environnementales: tous ont intérêt à prendre des mesures en faveur de l'environnement, mais chacun a intérêt à ce que les efforts soient essentiellement faits par les autres pays.

Une clef de lecture de l'engagement différencié des pays dans la lutte contre le dérèglement climatique réside dans la prise en compte de leurs intérêts définis selon leur vulnérabilité environnementale d'une part et les coûts économiques qu'une action engendre d'autre part. Il est possible d'obtenir une classification des comportements des États suivant ces deux paramètres. Ainsi, un État très vulnérable à la dégradation environnementale et capable de mettre en œuvre des mesures à bas coût sera un État leader dans la promotion de l'action publique. Au contraire, un État peu vulnérable et pour lequel une action en faveur de l'environnement sera très coûteuse sera obstructionniste. Par exemple, l'Alliance des petits États insulaires (AOSIS), très vulnérables à la montée des eaux, est très active en matière environnementale. Au contraire, l'Arabie saoudite qui retire de forts revenus de l'exploitation des énergies fossiles, comme le pétrole, est très obstructionniste. Cependant, ce modèle ne correspond pas toujours à la réalité, les pouvoirs publics, guidés par leurs valeurs peuvent agir en décidant de donner des droits à la nature : Équateur et Bolivie ont intégré dans leur constitution les droits de la «terre mère », la Pachamana. Les communautés locales sont chargées de faire respecter ces droits.

Pour faciliter les négociations et l'obtention de résultats en matière de lutte contre le dérèglement climatique, W. Nordhaus propose un cadre plus restreint aux négociations, réunissant des parties prenantes aux intérêts très proches, donc moins tentées par des stratégies de passager clandestin du fait de cobénéfices majeurs. Il s'agirait alors de constituer des « clubs climatiques ».