- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

Any mentions of the Ramsey formula, of the various interpretations of the discount rate for climate change by economists or of a generational conflict due to climate change.

US-3-m

569

A social discount rate that declines over time may be useful in planning for global warming or other future environmental disasters (Karp, 2005). Suppose that the harmful effects of greenhouse gases will not be felt for a century and that society used traditional, exponential discounting. We would be willing to invest at most 37¢ today to avoid a dollar’s worth of damages in a century if society’s constant discount rate is 1%, and only 2¢ if the discount rate is 4%. Thus, even a modest discount rate makes us callous toward our distant descendants: We are unwilling to incur even moderate costs today to avoid large damages far in the future. One alternative is for society to use a declining discount rate, although doing so will make our decisions time inconsistent. Parents today may care more about their existing children than their (not yet seen) grandchildren, and therefore may be willing to significantly discount the welfare of their grandchildren relative to that of their children. They probably have a smaller difference in their relative emotional attachment to the tenth future generation relative to the eleventh generation. If society agrees with such reasoning, our future social discount rate should be lower than our current rate. By reducing the discount rate over time, we are saying that the weights we place on the welfare of any two successive generations in the distant future are more similar than the weights on two successive generations in the near future.

US-5-m

697

Formulating environmental policy in the presence of stock externalities therefore introduces an additional complicating factor: What discount rate should be used? Because the costs and benefits of a policy apply to society as a whole, the discount rate should likewise reflect the opportunity cost to society of receiving an economic benefit in the future rather than today. This opportunity cost, which should be used to calculate NPVs for government projects, is called the social rate of discount. There is little agreement among economists as to the appropriate number to use for the social rate of discount. In principle, the social rate of discount depends on three factors: (1) the expected rate of real economic growth; (2) the extent of risk aversion for society as a whole; and (3) the “rate of pure time preference” for society as a whole. With rapid economic growth, future generations will have higher incomes than current generations, and if their marginal utility of income is decreasing (i.e., they are risk-averse), their utility from an extra dollar of income will be lower than the utility to someone living today; that’s why future benefits provide less utility and should thus be discounted. In addition, even if we expected no economic growth, people may simply prefer to receive a benefit today than in the future (the rate of pure time preference). Depending on one’s beliefs about future real economic growth, the extent of risk aversion for society as a whole, and the rate of pure time preference, one could conclude that the social rate of discount should be as high as 6 percent—or as low as 1 percent. And herein lies the difficulty. With a discount rate of 6 percent, it is hard to justify almost any government policy that imposes costs today but yields benefits only 50 or 100 years in the future (e.g., a policy to deal with global warming). Not so, however, if the discount rate is only 1 or 2 percent. Thus for problems involving long time horizons, the policy debate often boils down to a debate over the correct discount rate.

698

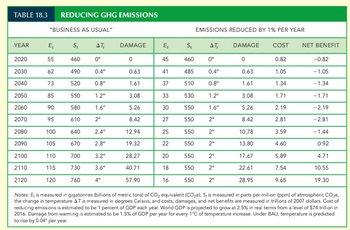

The problem is that the costs of reducing GhG emissions would occur today, but the benefits from reduced emissions would be realized only in some 50 or more years.

699

Does this emissions-reduction policy make sense? To answer that question, we must calculate the present value of the flow of net benefits, which depends critically on the discount rate. A review conducted in the United Kingdom recommends a social rate of discount of 1.3 percent. With that discount rate, the NPV of the policy is $11.41 trillion, which shows that the emissions-reduction policy is clearly economical. However, if the discount rate is 2 percent, the NPV drops to - $12.19 trillion, and with a discount rate of 3 percent, the NPV is - $23.68 trillion. We have examined a particular policy—and a rather stringent one at that—to reduce GhG emissions. Whether that policy or any other policy to restrict GhG emissions makes economic sense clearly depends on the rate used to discount future costs and benefits. Be warned, however, that economists disagree about what rate to use, and as a result, they disagree about what should be done about global warming.

US-6-m

425

Even further, climate change raises important questions about […] the present versus the future.

428

What accounts for the difference between the Stern Review and most earlier analyses? The primary difference was that Stern applied a lower discount rate, 1.4 percent, compared to 3–5 percent in most other studies. Stern argued that his discount rate reflected the view that each generation should have approximately the same inherent value. Stern’s analysis also incorporated the precautionary principle, in that he placed greater weight on the possibility of catastrophic damages.

429

Most of the costs of responding to climate change are borne in the short term, while most of the benefits (in terms of avoided damages) occur in the long term. Thus the choice of a discount rate is critical.

445

In addition, nature’s ability to absorb pollution and break down waste is limited, and there are tipping points beyond which degraded natural capital may be dramatically altered in some essential respect.

US-8-m

367

Although differences in time preferences themselves are not irrational per se because the future often appears so distant, it can blur the reasoning behind sound economic decisions. For example, a society’s unwillingness to fully tackle climate change results from overvaluing present benefits relative to future costs.

757

Studies reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predict that global sea levels will rise between 10 and 32 inches by the end of the century, highlighting the important idea that actions taken today, both positive and negative, will affect future generations.

799

A cost-benefit analysis provides a formal, rational model for policy decisions by focusing on the choices that are available, the preferences of individuals, and the present value of benefits and costs that will be incurred by today's and future generations.

[...]

Moreover, climate change has an intergenerational effect, as actions today will affect future generations.

802

However, reducing global warming is not a short-term objective but rather a cumulative process across many years. Yet, our short-run decisions will have immense impacts in the long run. Small changes in emissions today may have little effect on the current generation but will have sizable effects many decades out. This aspect of the problem seriously complicates policymaking and economic analysis.

807

Global climate change is a huge negative externality with an extremely long time horizon.

812

Global climate change is a huge global negative externality accompanied by public goods aspects and extremely long time horizons, making the inherent market failure difficult to address.

US-16-m

46

The evidence on biodiversity and climate change shows how dramatically the way we produce our livelihoods is now changing the environment, and depleting the stock of natural resources. By treating them as free, and using them up, we affect future (human) living standards and wellbeing.

460

Discount rates are central to the discussion in economics of how best to address climate change and other environmental damages. But what is discounted is not the value placed by a citizen on their consumption later (as opposed to consumption now) but instead the value we place on the consumption of people living in the future compared to our own generation. Our economic activity today will affect how climate changes in the distant future, so we are creating consequences that others will bear. This is an extreme form of external effects that we study throughout the book. It is extreme not only in its potential consequences, but also in that those who will suffer the consequences are future generations. But the future generations that will bear the consequences of our decisions are unrepresented in the policymaking process today. The only way the wellbeing of these unrepresented generations will be taken into account at the environmental bargaining tables is the fact that most people care about, and would like to behave ethically toward, others. These social preferences underlie the debates among economists about how much we should value the future benefits and costs of the climate change decisions that we make today.

In considering alternative environmental policies addressed to climate change, how much we value the wellbeing of future generations is commonly measured by an interest rate; that is, by applying the same MRS = MRT approach. This raises the question of what interest rate should be used to discount future generations’ costs or benefits. Economists disagree about how this discounting process should be done.

159-160

The Stern Review examined both scientific evidence and economic implications of climate change. Its conclusion, that the benefits of early action would outweigh the costs of neglecting the issue, was reinforced in 2014 by the United Nations Inter governmental Panel on Climate Change (UN IPCC). Early action would mean a significant cut in greenhouse gas emissions, by reducing our consumption of energy-intensive goods, a switch to different energy technologies, reducing the impacts of agriculture and land-use change, and an improvement in the efficiency of current technologies. These changes could not happen under what the Stern Review called ‘business as usual’, in which people, governments, and businesses were free to pursue their own pleasures, politics, and profits, taking little account of their effects on others, including future generations.

461-462

The discounting dilemma: How should we account for future costs and benefits?

When considering policies, economists seek to compare the benefits and costs of alternative approaches, often in cases where some people bear the costs and others enjoy the benefits. Doing this presents especially great challenges when the policy problem is climate change. The reason is that costs will be borne by the present generation, but most of the benefits of a successful policy to limit CO2 emissions, for example, will be enjoyed by people in the future, many of whom are not yet alive.

Put yourself in the shoes of an impartial policymaker and ask yourself: Are there any reasons why, in summing up the benefits and costs of such a policy, I should value the benefits expected to be received by future generations any less than the benefits and costs that will be borne by people today? Two reasons come to mind:

• Technological progress and diminishing marginal utility: People in the future may have lesser unmet needs than we do today. For example, as a result of continuing improvements in technology, they may be richer (either in goods or free time) than we are today, so it might seem fair that we should not value the benefits they will receive from our policies as highly as we value the costs that we will bear as a result.

• Extinction of the human species: There is a small possibility that future generations will not exist because humanity becomes extinct.

These are good reasons why we might discount the benefits received by future generations. Neither of these reasons for discounting is related to intrinsic impatience.

This was the approach adopted in the 2006 Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change. Nicholas Stern, an economist, selected a discount rate to take account of the likelihood that people in the future would be richer. Based on an estimate of future productivity increases, Stern discounted the benefits to future generations by 1.3% per annum. To this he added a 0.1% per annum discount rate to account for the risk that in any future year there might no longer be surviving generations. Based on this assessment, Stern advocated an urgent and fundamental shift in the policies of governments and businesses to ensure substantial investments to limit CO2 emissions today in order to protect the environment of the future.

Several economists, including William Nordhaus, criticized the Stern Review for its low discount rate. Nordhaus wrote that Stern’s choice of discount rate ‘magnifies impacts in the distant future’. He concluded that, with a higher discount rate, ‘the Review’s dramatic results [Stern’s policy conclusions above] disappear’.

Nordhaus advocated the use of a discount rate of 4.3%, which gave vastly different implications. Discounting at this rate means that a $100 benefit occurring 100 years from now is worth only $1.48 today, while under Stern’s 1.4% rate it would be worth $24.90. This means, a policymaker using Nordhaus’s discount rate would approve of a project that would save future generations $100 in environmental damages only if it cost less than $1.48 today. A policymaker using Stern’s 1.4% would approve the project only if it cost less than $24.90.

Not surprisingly, then, Nordhaus’s recommendations for climate change abatement were far less extensive and less costly than those that Stern proposed. For example, Nordhaus proposed a carbon price of $35 per ton in 2015 to deter the use of fossil fuels, whereas Stern recommended a price of $360.

Why did the two economists differ so much? They agreed on the need to discount for the likelihood that future generations would be better off. But Nordhaus had an additional reason to discount future benefits: intrinsic impatience.

Reasoning as we did in Julia’s choice of consumption now or later, Nordhaus used estimates based on market interest rates (the slope of the feasible set) as measures of how people today value their own future versus present consumption. Using this method, he came up with a discount rate of 3% to measure the way people discount future benefits and costs that they themselves may experience. Nordhaus included this in his discount rate, which is why Nordhaus’s discount rate (4.3%) is so much higher than Stern’s (1.4%).

Critics of Nordhaus pointed out that a psychological fact like our own impatience—how much more we value our own consumption now versus later—is not a reason to discount the needs and aspirations of other people in future generations. Stern’s approach counts all generations as equally worthy of our concern for their wellbeing. Nordhaus, in contrast, takes the current generation’s point of view and counts future generations as less worthy of our concern than the current generation, much in the way that, for reasons of intrinsic impatience, we typically value current consumption more highly than our own future consumption.

Is the debate resolved? The discounting question ultimately requires adjudicating between the competing claims of different individuals at different points in time. This involves questions of ethics on which economists will continue to disagree.

464

Some economists (M. Fleurbaey, S. Zuber) have suggested that the discount rate for future environmental benefits and costs should be negative, meaning that we value benefits and costs experienced by future generations more than those experienced by the current generation.

FR-2-m

310

Au niveau le plus global qui soit, il est clair que le réchauffement climatique est un exemple dramatique de tragédie des communs: chacun a individuellement tendance à surconsommer des produits polluants, car cela augmente son bien-être instantané, mais si tout le monde a la même attitude, le réchauffement du climat qui en résulte va dégrader la situation de tous les individus et des générations futures.

FR-4-M

311

Toute politique qui cause des coûts à court terme pour des bénéfices difficiles à évaluer et dans un futur lointain est difficile à vendre politiquement.

FR-4-B

490-491

D'autres économistes, comme W. Nordhaus, préconisent un taux d'actualisation positif, mais élevé, de 4,5 %, car les générations futures, si la tendance séculaire se poursuit, seront plus riches que les générations passées et donc plus à même de financer les dépenses liées à la protection de l'environnement. Enfin, N. Stern préconise un taux d'actualisation de 1,4 %, traduisant une faible préférence pour le présent, ce qui avantage les générations futures. À ce taux, de nombreux projets non rentables dans le schéma d'actualisation de W. Nordhaus peuvent voir le jour.

499-500

Le financement de la transition vers une économie bas-carbone se heurte à des obstacles qui empêchent l'épargne de s'orienter vers les investissements de long terme. Des mesures sont alors nécessaires.

Le paradoxe actuel du système financier mondial est qu'il existe une épargne abondante, alors que les investissements de long terme sont trop faibles. M. Carney, ancien gouverneur de la Banque d'Angleterre, dans un discours en 2015, l'explique par « la tragédie de l'horizon ». L'horizon du coût de l'inaction climatique va bien au-delà de celui des décideurs politiques, borné par leur mandat, ou des décideurs économiques, dans le cadre d'une gouvernance court-termisme actionnariale.