- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

Any statement on the Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs will be recorded under this section. We will also include mentions of abatement costs from a cost-benefit analysis point of view.

US-3-m

569

A social discount rate that declines over time may be useful in planning for global warming or other future environmental disasters (Karp, 2005). Suppose that the harmful effects of greenhouse gases will not be felt for a century and that society used traditional, exponential discounting. We would be willing to invest at most 37¢ today to avoid a dollar’s worth of damages in a century if society’s constant discount rate is 1%, and only 2¢ if the discount rate is 4%. Thus, even a modest discount rate makes us callous toward our distant descendants: We are unwilling to incur even moderate costs today to avoid large damages far in the future. One alternative is for society to use a declining discount rate, although doing so will make our decisions time inconsistent. Parents today may care more about their existing children than their (not yet seen) grandchildren, and therefore may be willing to significantly discount the welfare of their grandchildren relative to that of their children. They probably have a smaller difference in their relative emotional attachment to the tenth future generation relative to the eleventh generation. If society agrees with such reasoning, our future social discount rate should be lower than our current rate. By reducing the discount rate over time, we are saying that the weights we place on the welfare of any two successive generations in the distant future are more similar than the weights on two successive generations in the near future.

US-4-m

1031

What is the social cost of carbon?

In 2011, three leading economists, Nicholas Z. Muller, Robert Mendelsohn, and William Nordhaus, published a paper estimating the external cost of pollution by various U.S. industries. The costs took a variety of forms, from harmful effects on health to reduced agricultural yields. In the case of the electricity-generation sector, the authors included costs from carbon dioxide emissions—one of the many greenhouse gases that cause climate change. The authors used a conservative, relatively low estimate because valuing these costs is a contentious issue—in part because they will fall on future generations. For each industry they calculated the total external cost of pollution, or TEC. Remarkably, in a number of cases this cost actually exceeded the industry’s value added (VA), that is, the market value of its output. This doesn’t mean that these industries should be shut down, but it’s a clear indication that markets weren’t taking the costs of pollution into account.

1044

However, it is now widely recognized that the direct cost of fossil fuel consumption greatly underestimates the social cost. Environmental economists have argued that the price per tonne of carbon should have been $103 in 2015, climbing to $260 by 2035, in order to account for its environmental costs. That’s far more than the going carbon price in world markets. In the United States in 2015, that price stood at approximately $20 per tonne.

US-8-m

799

The choice to engage in actions to minimize climate change by individuals, businesses, and governments is one that involves a cost-benefit analysis. A cost-benefit analysis provides a formal, rational model for policy decisions by focusing on the choices that are available, the preferences of individuals, and the present value of benefits and costs that will be incurred by today's and future generations.

[...]

The challenge with using cost-benefit analysis for environmental policies is that many of the benefits and costs are difficult to quantify. For example, what is the cost of living in a polluted city? What is the benefit of preventing a species from going extinct? The answers require a more thorough understanding of the causes and effects of climate change. Moreover, climate change has an intergenerational effect, as actions today will affect future generations. This has led many corporations and countries to adopt sustainable development goals, which refers to the ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

US-11-m

360-361

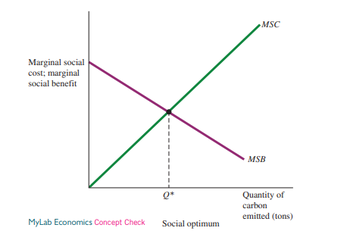

Figure 16.2 presents this analysis graphically. Along the horizontal axis we measure the level of pollution; here we have used tons of carbon emitted. On the vertical axis we represent the marginal social cost of experiencing carbon emissions (green line) and the marginal social benefit from pollution (purple line). It is interesting to think about the slopes of these two curves. As we increase emissions levels, the MSC increases; the MSC curve slopes up. This tells us that as we increase emissions the added cost of one more unit of emissions goes up. For many pollutants the environment can absorb low levels reasonably well, so marginal costs at low levels are low. As we dump more pollutants into the environment, however, the harm to nature generally increases. [...] Figure 16.2 presents the MSC as a straight line, but that will often not be the case. For example, the slope of the MSC curve may increase quite dramatically as the environment approaches a saturation point. The marginal social benefit curve shown in the figure has, by contrast, a downward slope. At high levels of emissions (on the right in the graph), there are often cheap ways to eliminate some emissions. Cutting back a ton of carbon emissions at this level may be quite cheap. Thus, the benefits from being able to pollute are small.

[...]

We see the optimum emissions level in Figure 16.2 is Q*, found at the intersection of the MSC and MSB curves. At this point, society is using its environment most efficiently, weighing the reduction in costs from experiencing pollution against the lost benefits from changing consumption or investing resources in mitigation.

Drawing the marginal curves as we have done and identifying the optimal level of pollution is a relatively straightforward application of the principles of marginalism that we have covered often in this text. It is a more difficult challenge to empirically measure these curves. The MSC of emissions ranges from health costs, to aesthetics, to loss of species diversity, or even to increases in risks to populations from rising sea levels. Many of these risks are uncertain and some occur only in the future. Environmental economists working with natural scientists have spent considerable time trying to provide reasonable estimates of what these costs might be. It is not easy to estimate the marginal social benefit curves, which requires us to assess the costs of technological solutions to emissions problems.

366

These countries can adopt indirect policies such as imposing fuel taxes, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, and regulations that may incorporate a “social cost of carbon.”

US-15-m

606

One of the most important economic numbers in policy debates about climate change is the social cost of carbon (SCC). The SCC is the negative externality that will result from one additional unit of carbon dioxide emissions through its effects on climate change. Another way to describe the SCC is that it is how big the Pigouvian tax would have to be to lead to the socially optimal amount of carbon dioxide emissions.

Many environmental economists have tried to measure the social cost of carbon. It isn't easy, there is a lot of uncertainty about how the climate works, the types and magnitudes of economic effects that climate change will have, and how much people today should weigh the welfare of future generations. All these factors need to be taken into account to arrive at an estimate. That's why the estimates have varied widely, from less than $20 per metric ton to over $600 per metric ton.

A recent estimate by the Nobel Prize-winning economist William Nordhaus has received a lot of attention. Using the latest version of a large model of the climate and the economy, he computes a SCC of about $36 per metric ton (in 2018 dollars). To put that in perspective, a typical car produces about 5 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. Therefore, if Nordhaus's calculation was used to establish a climate change Pigouvian tax, it would be about $180 per year for a typical car.

You might be thinking, "Well, it's not as if $180 a year is nothing, but I would still keep driving if this was the tax. How is that going to stop my carbon emissions?" The answer is that it won't stop your carbon emissions, nor should it. You derive a benefit from being able to drive around; that's why you would pay the tax. Without a carbon tax, you would add to the climate change problem without paying for the damage you are doing. If a tax is imposed (and it is set at the true social cost of carbon dioxide emissions), you would pay for exactly the amount of damage you do. You will balance this cost against the benefit you obtain from your car and drive the optimal amount from a social perspective. This will be less than the amount you drove when there was no tax and you did not pay for your negative externality, but it will be more than nothing.

FR-7-M

53

L'économiste américain William Nordhaus a développé des modèles, notamment le Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy (DICE) permettant de calculer, sous plusieurs hypothèses, la réduction du PIB futur que causent les émissions de gaz à effet de serre. Sans action, les modèles prédisent qu'une hausse de la température de 2 degrés pourrait coûter à l'économie mondiale jusqu'à 2 points de PIB, et qu'une hausse de 3 degrés, 5 points de Produit Intérieur Brut! Chaque tonne de carbone rejetée dans l'atmosphère a ainsi un coût pour l'économie de quelques dizaines à plusieurs centaines de dollars.

FR-4-B

37

W. Nordhaus (Prix Nobel 2018) (né en 1941) va proposer dans les années 1990 le modèle DICE (pour Dynamic integrated climate-economy) qui per- met de mesurer les coûts futurs des effets des émissions de gaz à effet de serre (le taux d'actualisation) pour déterminer le prix présent des activités émettrices. Ces travaux avaient pour objectif de modéliser l'interaction entre la croissance économique et le changement climatique.

481

Le rapport rédigé par N. Stern en 2006 (économiste britannique, ancien vice-président de la Banque mondiale) évalue le coût de l'inaction contre le changement climatique de 5 % à 20 % du Produit intérieur brut (PIB) mondial.

497

Donner une valeur sociale au carbone permettrait plus de lisibilité pour les investissements des entreprises et des pouvoirs publics, augmenterait les financements nécessaires à la transition énergétique. Elle pourrait, selon M. Aglietta être croissante avec le temps. […]