- Home

- SUMMARY

- BY TEXTBOOK Apri sottomenù

-

BY TOPIC

Apri sottomenù

- S1 : Greenhouse effect

- S2 : Anthropogenic cause

- S3 : Future scenarios of temperature increases

- S4 : Impacts on Earth’s systems

- S5 : Impacts on economic and social systems

- E1 : Mitigation as a social dilemma

- E2 : Carbon pricing

- E3 : Discounting in reference to climate change

- E4 : Inequality in reference to climate change

- E5 : Social Cost of Carbon and IAMs

- E6 : Persistency & irreversibility in reference to climate change

- E7 : Climate decision-making under uncertainty

- E8 : Climate policies

- E9 : Behavioural issues in reference to climate change

- E10 : Adaptation and geoengineering

- SAMPLE LECTURE

- ABOUT US

E2 : Carbon pricing

Any statement on carbon taxes or on cap-and-trade systems related to climate change will be recorded under this section.

US-1-m

286

The price you pay for a gallon of gasoline does not reflect the costs imposed by the greenhouse gases, sootier air, oil spills, and greater congestion and accidents your driving creates.

287

Electricity production involves not only the private cost of the resources employed but also the external cost of using the atmosphere as a dump for greenhouse gases.

288

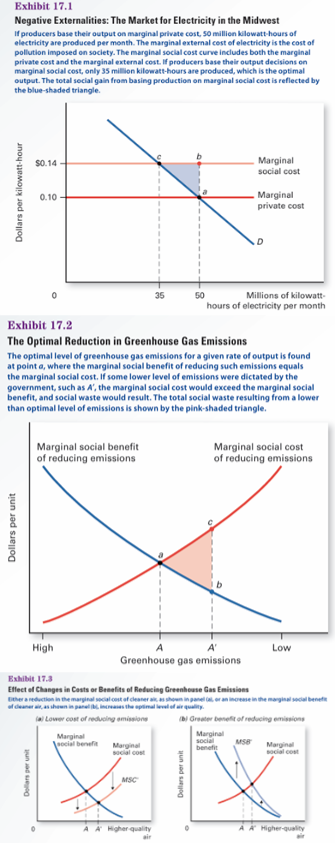

With a tax of $0.04 per kilowatt-hour, the equilibrium combination of price and output moves from point a to point c. The price rises from $0.10 to $0.14 per kilowatt-hour, and output falls to 35 million kilowatt hours. Setting the tax equal to the marginal external cost results in the efficient level of output. At point c, the marginal social cost of production equals the marginal benefit. Notice that greenhouse gas emissions are not eliminated at point c, but the utilities no longer generate electricity for which marginal social cost exceeds marginal benefit. The social gain from reducing production to the socially optimal level is shown by the blue-shaded triangle in Exhibit 17.1. This triangle also measures the social cost of allowing firms to ignore the external cost of their production. Although Exhibit 17.1 offers a tidy solution, the external costs of greenhouse gases often can not be easily calculated or taxed. At times, government intervention may result in more or less production than the optimal solution requires.

289

The previous example assumes that the only way to reduce greenhouse gases is to reduce output. But power companies, particularly in the long run, can usually change their resource mix to reduce emissions for any given rate of electricity output. Let’s look at Exhibit 17.2. The horizontal axis measures greenhouse gas emissions for a given rate of electricity production. Emissions can be reduced by adopting cleaner production technology. Yet the production of cleaner air, like the production of other goods, is subject to diminishing returns. Cutting emissions of the most offensive greenhouse gases may involve simply changing the fuel mix, but further reductions could require more sophisticated and more expensive processes. Thus, the marginal social cost of reducing greenhouse gases increases, as shown by the upward-sloping marginal social cost curve in Exhibit 17.2.The marginal social benefit curve reflects the additional benefit society derives from greenhouse gas reductions. The optimal level of air quality for a given rate of electricity production is found at point a, where the marginal social benefit of cleaner air equals the marginal social cost. In this example, the optimal level of greenhouse gas emissions is A. If firms made their production decisions based simply on their private cost— that is, if the emission cost is external to the firm—then firms would have little incentive to search for production methods that reduce green house gas emission, so too much pollution would result.

290

For example, suppose some technological breakthrough reduces the marginal cost of cut ting greenhouse gas emissions. As shown in panel (a) of Exhibit 17.3, the marginal social cost curve of reducing emissions would shift downward to ′ MSC , leading to cleaner air as reflected by the movement from A to ′ A . The simple logic is that the lower the marginal cost of reducing greenhouse gases, other things constant, the cleaner the optimal level of air quality. Exhibit 17.3. The greater the marginal benefit of reducing greenhouse gases, other things constant, the cleaner the optimal level of air quality.

US-2-m

40

Some microeconomists undertake normative analysis of coal-based pollution. For example, because global warming is largely caused by carbon emissions from coal, oil, and other fossil fuels, microeconomists design new government policies that attempt to reduce the use of these fuels. For example, a “carbon tax” targets carbon emissions. Under a carbon tax, relatively carbon-intensive energy sources—like coal-fired power plants— pay more tax per unit of energy produced than energy sources with lower carbon emissions—like wind farms. Some microeconomists have the job of designing interventions like carbon taxes and determining how such interventions will affect the energy choices of households and firms.

264

As you eat breakfast, you decide to flip on the TV to learn more about the candidates. You listen to a persuasive argument from the Democratic candidate, who is urging businesses to reduce their carbon emissions. She states that if elected, she will propose new taxes on polluters to address the inherent dangers of climate change: polluters must pay for their pollution! This makes sense to you: why not levy a tax on polluters to more closely align their interests with those of society? She closes by confidently stating that “now is the time to improve our lives, with the helping hand of a government working for you.”

US-3-m

67

Regularly, at international climate meetings—such as the one in Paris in 2015—government officials, environmentalists, and economists from around the world argue strongly for an increase in the tax on gasoline and other fuels (or, equivalently, on carbon) to retard global warming.

628

Driving causes many externalities including pollution, congestion, and accidents. Taking account of pollution from producing fuel and driving, Hill et al. (2009) estimated that burning one gallon of gasoline (including all downstream effects) causes a carbon dioxide-related climate change cost of 37¢ and a health-related cost of conventional pollutants associated with fine particulate matter of 34¢. A driver imposes delays on other drivers during congested periods. Parry et al. (2007) estimated that this cost is $1.05 per gallon of gas on average across the United States. Edlin and Karaca-Mandic (2006) measured the accident externality from additional cars by the increase in the cost of insurance. These externalities are big in states with a high concentration of traffic but not in states with low densities. In California, with lots of cars per mile, an extra driver raises the total statewide insurance costs of other drivers by between $1,725 and $3,239 per year, and a 1% increase in driving raises insurance costs 3.3% to 5.4%. While the state could build more roads to lower traffic density and hence accidents, it’s cheaper to tax the externality. A tax equal to the marginal externality cost would raise $66 billion annually in California—more than the $57 billion raised by all existing state taxes—and over $220 billion nationally. As of 2015, Germany, Austria, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and Switzerland have some form of a vehicle miles traveled tax (VMT), which is more clearly targeted at preventing congestion and accidents. Vehicles are inefficiently heavy because owners of heavier cars ignore the greater risk of death that they impose on other drivers and pedestrians in accidents (Anderson and Auffhammer, 2014). Raising the weight of a vehicle that hits you by 1,000 pounds increases your chance of dying by 47%. The higher externality risk due to the greater weight of vehicles since 1989 is 26¢ per gallon of gasoline and the total fatality externality roughly equals a gas tax of between 97¢ and $2.17 per gallon. Taking account of both carbon dioxide emissions and accidents, Sheehan-Connor (2015) estimates that the optimal flat tax is $1.14 per gallon. In 2014, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated the optimal tax for the United States as $1.60 per gallon for gasoline and $2.10 for diesel. To reduce the negative externalities of driving, governments have taxed gasoline, cars, and the carbon embodied in gasoline. However, such taxes have generally been much lower than the marginal cost of the externality and have not been adequately sensitive to vehicle weight or time of day.

US-4-m

443-444

The U.S. government is considering reducing the amount of carbon dioxide that firms are allowed to produce by issuing a limited number of tradable allowances for carbon dioxide (CO2 ) emissions. In a recent report, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) argues that “most of the cost of meeting a cap on CO2 emissions would be borne by consumers, who would face persistently higher prices for products such as electricity and gasoline.

495-496

A carbon tax is a tax on a good or service assessed according to the amount of carbon dioxide created by the production of that good or service. Carbon dioxide is one of the main pollutants behind global climate change.

A Microsoft business unit determines its carbon tax levy by calculating the total amount of energy that it consumes for its operations—such as the energy consumed for its office space, data centers, or business travel. Next, the amount of energy consumed is converted into metric tons of carbon—the amount of carbon emissions generated by the unit’s consumption of energy. Microsoft’s Environmental Sustainability Team then calculates each unit’s carbon tax. In 2015, Microsoft collected approximately $20 million in carbon tax revenue from its business units. Finally, the carbon tax revenue is placed in a fund that pays for a range of clean energy projects within Microsoft. For example, at its corporate headquarters in Redmond, Washington, carbon tax revenue paid for a data collection and software system that optimized energy use across 125 buildings, leading to huge cost and carbon-emissions savings. In its first three years, the carbon tax system has led to a $10 million savings for Microsoft through reduced energy consumption and a 7.5 million metric ton reduction in carbon emissions. Although the internal carbon tax scheme reduces the company’s profit in the short run, Microsoft’s shareholders support the scheme. They believe that reducing energy consumption in the long run will lead to higher future profits. Furthermore, some observers believe that internal carbon taxes put companies adopting them a step ahead as global climate change increases the likelihood that governments will adopt policies to reduce carbon emissions.

1045-1046

In 2005 the first cap and trade system for trading greenhouse gases—called carbon trading—was launched in the European Union. In the decade since then, carbon trading has grown rapidly around the world and now covers 8% of all man-made greenhouse gas emissions. In the past five years, several new greenhouse gas markets have been launched covering California, South Korea, Quebec, and three major industrial centers in China. In 2015, approximately $75 billion in permits were traded globally. Yet cap and trade systems are not silver bullets for the world’s pollution problems. Although they are appropriate for pollution that’s geographically dispersed, like sulfur dioxide and greenhouse gases, they don’t work for pollution that’s localized, like groundwater contamination. And there must be vigilant monitoring of compliance for the system to work. Finally, the level at which the cap is set has become a difficult political issue for governments trying to run an effective cap and trade system. The political problems stem from the fact that a lower cap imposes higher costs on companies, because they must either achieve great pollution reductions or because they must purchase permits that command a higher market price. So companies lobby governments to set higher caps. As of 2015 only four countries (Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Switzerland) had caps that met or exceeded $44 per metric ton, the carbon price that the International Emissions Trading Association estimates is required to avert catastrophic climate change. In fact, most carbon trading prices are well below $15. As one energy economist stated, “It is politically difficult to get carbon prices to levels that have an effect.” And the same applies for taxes on carbon, as higher taxes can be a hard sell to consumers and producers. So although carbon trading and carbon taxes are the efficient ways to reduce greenhouse emissions, their susceptibility to political pressure is making policy makers turn to regulations instead. A case in point is the adoption in 2014 by the EPA of rules limiting the emissions from newly built coal-fired and natural gas–fired plants. And in 2016, the Obama Administration adopted a mandate that doubles the fuel efficiency of cars by 2025.

1386

A carbon tax will increase the cost of using fossil fuels, including the prices of gasoline and coal. As the cost of fossil fuels increases, consumers will reduce their use of fossil fuels as energy sources. They will be increasingly likely to purchase more fuel-efficient cars and invest in solar technology for their homes.

US-5-m

698

GhG emissions could be reduced from their current levels—governments, for example, could impose stiff taxes on the use of gasoline and other fossil fuels—but this solution would be costly.

US-6-m

145

They suggest that gasoline taxes may be an effective means to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

370

Environmental taxes: Such a tax is levied on goods and services in proportion to their environmental impact. One example is a carbon tax, which taxes products based on the carbon emissions attributable to their production or consumption. The rationale of environmental taxation is that it encourages the use and development of goods and services with reduced environmental impacts. Like other taxes on goods and services, environmental taxes can be regressive—suggesting that environmental taxes need to be combined with other progressive taxes or rebates for low-income households. Among developed countries, the United States collects the smallest share of tax revenues from environmental taxes, both as a share of GDP and as a share of total tax revenues. The countries that collect the most in environmental taxes, as a share of all taxes, include India (13 percent of all taxes), Costa Rica (10 percent), South Korea (9 percent), and the Netherlands (9 percent).

401

Under a permit system, the level of pollution is known because the government sets the number of available permits. But the price of permits is unknown, and permit prices can vary significantly over time. This has been the case with the European permit system for carbon emissions. The price of permits initially rose to around €30/ton in 2006, shortly after the system was instituted. But then prices plummeted to €0.10/ton in 2007, when it became evident that too many permits had been allocated. After some changes to the system, prices rose to exceed €20/ton in 2008 but then fell again to less than €3/ton in 2013 before slightly increasing over the last few years. Such price volatility makes it difficult for firms to decide whether they should make investments in technologies to reduce emissions.

403

The other major attempt at emissions trading has been the European Union’s carbon trading system, enacted in 2005. The initial phase covered major facilities such as electricity plants, cement plants, and paper mills. In 2012 the program was extended to cover airline transportation. As mentioned earlier, the main problem with the program has been price volatility, generally attributed to an over-allocation of permits during the initial phases. In the current phase (2013–2020) the European Union is moving toward setting an overall EU emission limit rather than individual national limits.

428

Virtually all economists agree that carbon emissions represent a negative externality and that a market-based policy such as a Pigovian tax or a tradable permit system should internalize this externality. However, there is a lively debate among economists about how aggressive such policies should be. Until recently, most economic studies of climate change suggested a relatively modest carbon tax, perhaps around $20–$40 per ton of carbon emitted (a $30 per ton tax on carbon would increase the price of gasoline by about 8 cents per gallon).

The Stern Review estimated that if humanity continues “business as usual,” the costs of climate change in the twenty-first century would reach t least 5 percent of global GDP and could be as high as 20 percent. It also suggested the need for a much higher carbon tax—over $300 per ton of carbon.

428-429

Because climate change can be considered a very large environmental externality associated with carbon emissions, economic theory suggests a carbon tax as an economic policy response. Alternatively, a tradable permit system (also known as cap-and-trade) could be applied to carbon emissions. As discussed in Chapter 12, a tax offers price certainty, while a tradable permit system offers emissions certainty. If you take the perspective that price certainty is important because it allows for better long-term planning, then a carbon tax is preferable. If you believe that the relevant policy goal is to reduce carbon emissions by a specified amount with certainty, then a cap-and-trade approach is preferable, although it may lead to some price volatility. Both approaches have been used. Carbon taxes have been instituted in several countries, including a nationwide tax on coal in India (about $1/ton, enacted in 2010), a tax on new vehicles based on their carbon emissions in South Africa (initiated in 2015), a carbon tax on fuels in Costa Rica (enacted in 1997), and local carbon taxes in the Canadian provinces of Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta that apply to large carbon emitters and motor fuels. The European Union instituted a cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions in 2005. The system covers more than 11,000 facilities that collectively are responsible for nearly half the EU’s carbon emissions. In 2012 the system was expanded to cover the aviation sector, including incoming flights from outside the EU. The goal of the EU program is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 percent, relative to 1990 levels, by 2040. The state of California instituted a cap-and-trade system in 2013 for electrical utilities and large industrial facilities, with a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in 2050 by 80 percent, relative to 1990 levels.

US-7-m

146

He [Darren Woods] confirmed the company’s support for a carbon tax, under which the federal government would tax energy consumption on the basis of the carbon content of the energy. For example, oil refiners like ExxonMobil would pay a tax on the carbon content of the oil they were refining into products such as gasoline and home heating oil, and electric utilities like Pacific, Gas, & Electric (PG&E) would pay a tax on the carbon content of the coal and natural gas they burn to generate electricity.

[...]

A carbon tax is an example of a market-based policy that provides households and firms with an economic incentive to reduce their use of those fuels by raising their price. Government policies to reduce pollution, including the carbon tax, have been controversial, however. Some businesses oppose the carbon tax because they believe it will raise their costs of production. Other businesses view the carbon tax favorably, particularly in comparison with command-and-control policies that they see as more costly and less effective. In addition, command-and-control policies can be complex and difficult for government regulators to administer, so oil firms, electric utilities, and other firms subject to the policies face uncertainty about how they will be able to operate in the future. A carbon tax would provide these firms with greater certainty. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, a spokesman for ExxonMobil argued, “A straightforward carbon tax . . . is far preferable to the patchwork of current and potential regulations on the state, federal and international levels.”

162

For instance, the Canadian province of British Columbia has enacted a Pigovian tax on carbon dioxide emissions and uses the revenue raised to reduce personal income taxes.

164

In 2017, economists working at the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Tax Analysis estimated that the marginal social cost of carbon dioxide emissions was about $49 per metric ton. A carbon tax would be intended to replace other regulations on the emissions of carbon dioxide, relying instead on market forces responding to an increase in the price of products that result in carbon dioxide emissions. For example, a $49 per ton carbon tax would raise the price of gasoline by about $0.44 per gallon. This price increase would lead some consumers to switch from cars and trucks with poor fuel mileage to vehicles, including electric cars and trucks, with higher fuel mileage. The federal government’s Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, which require car companies to achieve an average of 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025, would no longer be necessary. Treasury Department economists estimate that a carbon tax that was set at $49 per ton and increased to $70 per ton over 10 years would raise tax revenue of about $2.2 trillion over that period. Because lower-income households spend a larger fraction of their incomes on gasoline, heating oil, and other energy products than do higher-income households, they would bear a proportionally larger share of the tax. Most proposals for a carbon tax, including one made in 2017 by former Republican secretaries of state George Schultz and James Baker, include a way of refunding to lower-income households some part of their higher tax payments, possibly by increasing and expanding eligibility for the earned income tax credit.

164-165

Some policymakers opposed implementing a carbon tax because they preferred the command-and-control approach of directly regulating emissions. Other opponents worried that a tax generating trillions of dollars of revenue might disrupt the economy in unanticipated ways, even if most of the revenue was refunded back to households. As of late 2017, it seemed doubtful that Congress would pass a carbon tax. The debate over policies to deal with global warming is likely to continue for many years.

179

A price on carbon would minimize the cost of steering economic activity away from the greenhouse gas emissions that threaten the climate.

US-8-m

795

Increasing attention to climate change has motivated organizations to create innovative solutions, such as markets for carbon offsets. For example, an individual can purchase a carbon offset based on an activity, such as an airline flight. These funds are used to invest in projects that reduce greenhouse gases, such as restoring forests or improving energy efficiency.

[…]

Although the United States does not use tradable permits at the federal level, at least eleven states use market-based policies to limit greenhouse gases. These efforts to reduce greenhouse gases are aimed at tackling the major problem of climate change.

796

Today, much discussion centers on the proposed use of cap-and-trade to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Such programs are law in the European Union and even China, but proposals to pass cap-and-trade legislation in the United States since 2008 have been held up, ironically by the same market-based proponents who created the strategy that worked in the past. Opponents of cap-and-trade today argue that cap-and-trade still imposes harsh limits on the broader market. Yet, without cap-and-trade, resolutions to reduce global warming become less likely. It may take another unlikely alliance before the problem of global warming is solved.

802

Cleaning up pollution problems typically involves finding a level of abatement at which the marginal costs of abatement equal the marginal benefits. This can be achieved by taxing, assigning marketable permits, or using command and control policies to limit emissions.

812

Environmental policy aimed at addressing market failure takes on several forms:

• Command and control: Fixed standards for polluters that are enforced through inspections and legal action (does not always lead to optimal pollution levels).

• Emissions taxes: A fee that is paid to the government per unit of pollution emitted (can lead to optimal pollution levels if the fee is set appropriately).

• Pollution permits: Also known as cap-and-trade, allows firms to buy, sell, and trade permits to pollute (can lead to optimal pollution levels).

US-9-m

202-203

In January 2019, thousands of economists, including 27 Nobel laureates signed an open letter arguing that the best way to address the problem of climate change was a carbon tax. To quote the letter:

1. A carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary. By correcting a well-known market failure, a carbon tax will send a powerful price signal that harnesses the invisible hand of the marketplace to steer economic actors toward a low-carbon future.

2. A carbon tax should increase every year until emissions reductions goals are met and be revenue neutral to avoid debates over the size of government. A consistently rising carbon price will encourage technological innovation and large-scale infrastructure development. It will also accelerate the diffusion of carbon-efficient goods and services.

3. A sufficiently robust and gradually rising carbon tax will replace the need for various carbon regulations that are less efficient. Substituting a price signal for cumbersome regulations will promote economic growth and provide the regulatory certainty that companies need for long-term investment in clean-energy alternatives.

4. To prevent carbon leakage and to protect U.S. competitiveness, a border carbon adjustment system should be established. This system would enhance the competitiveness of American firms that are more energy-efficient than their global competitors. It would also create an incentive for other nations to adopt similar carbon pricing.

5. To maximize the fairness and political viability of a rising carbon tax, all the revenue should be returned directly to U.S. citizens through equal lump-sum rebates. The majority of American families, including the most vulnerable, will benefit financially by receiving more in "carbon dividends" than they pay in increased energy prices.

Using what we have learned in this chapter, we can now understand each of these points. […] But note that the economists argue that the goal of a carbon tax is not to eliminate all carbon emissions, but to solve the market failure by correctly pricing carbon emissions. Remember, a price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. Thus, by correctly pricing carbon emissions the market will send a signal about the true cost of different products and services and that signal will incentivize demanders and suppliers to reduce high-carbon products and develop substitutes. In other words, when carbon emissions are correctly priced, self-interest will align with the social interest so the invisible hand can steer economic actors in the right direction.

Point 1 also tells us that a carbon tax offers the most "cost-effective" lever to reduce carbon emissions. Point 2 explains some of the reasons why. A carbon tax operates on many margins. A carbon tax will encourage demanders to switch from higher-priced carbon-intensive goods and services to lower-priced, less-carbon intensive substitutes. At the same time, suppliers will be encouraged to research and develop less carbon-intensive goods and services. Over time a carbon tax will even encourage large-scale changes in how energy is generated, where people work and live and how they transport as well as produce goods and services.

Point 3 says that a carbon tax is better than command and control regulations. Remember the clothes washers that didn't work after command and control regulations on energy efficiency were imposed before the available technology was cost-effective? The same principles apply to a carbon tax. Instead of requiring that every new home install solar panels, a potentially very costly mandate imposed in California, the economists are suggesting that we apply a carbon tax and let people decide how to reduce carbon emissions in the least costly way. Command and control works on only a few margins, whereas a carbon tax works across many margins in ways that are too complex for planners to predict or plan. [...] A carbon tax uses the forces of creative destruction, which brought us cell phones, online dating, and movies on demand, to address the challenge of climate change.[…] A carbon tax is unlikely to be effective if it is imposed by the United States alone. Indeed, it could be even counterproductive if relatively low-carbon U.S. producers were taxed but not higher-carbon foreign competitors. Thus, Point 4 suggests a border adjustment scheme so that at least within the United States all producers, foreign and domestic, would be taxed on a level playing field. The United States is one of the world's largest markets, so Point 4 suggests that this will encourage other countries to adopt carbon taxes. Getting both the economics and the politics right is one of the most difficult parts of designing a global carbon tax.

204

The politics of a carbon tax are also discussed in Points 2 and 5. Point 2 argues that a carbon tax should be "revenue neutral." The signatories to the letter don't necessarily agree on whether the government should spend more or less money on defense or Medicare or the National Institutes of Health. What they do agree on is that a carbon tax is the best way to reduce atmospheric carbon emissions. To get everyone on board, therefore, the economists suggest that all the money raised by the carbon tax should be returned to the residents of the United States. One possibility, for example, is to reduce income taxes by a dollar for every dollar raised by the carbon tax - tax burning not earning. Another possibility is to give each U.S. citizen an equal "carbon dividend." Here the economists' signatories are making a political point. A carbon-dividend might be a good way of selling the carbon tax to a large number of voters, especially as the dividend would be more than most voters would pay in tax.

In 2013, however, the United Kingdom introduced a carbon tax and coal use began a rapid and dramatic decline as shown in Figure 10.5. By 2017, coal accounted for only 5% of energy use. By 2025, it's expected that coal will be phased out entirely.

205

The United Kingdom's carbon tax raised the price of coal relative to other energy sources such as solar, wind, and natural gas. Natural gas is a carbon-emitting fuel, but it emits carbon at half the rate of coal for the same amount of energy, so switching to natural gas reduced the tax on electricity generators and the tax on the environment. Other countries around the world have also introduced carbon taxes. Canada has a carbon tax and the revenues from the tax are rebated back to Canadian citizens. Mexico, Australia, and Norway also have carbon taxes, and China is planning to slowly introduce the largest tradeable allowance program for carbon (cap and trade) in the world beginning in 2020. Although there is no federal carbon tax in the United States, California has a tradeable allowance program, and there are several regional programs, including the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative that covers nine states in the Northeast.

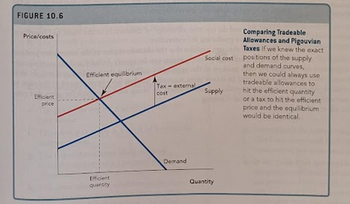

205-206

There is a close relationship between using carbon taxes and tradeable allowances to solve the externality problem. A tax set equal to the level of the external cost is equivalent to tradeable allowances, where the number of allowances. is set equal to the efficient quantity. To achieve the efficient equilibrium in Figure 10.6, for example, the government can either use taxes to raise the price to the efficient price or it can use allowances to reduce the quantity to the efficient quantity. The equilibrium is identical no matter which method is used. A major difference between taxes and tradeable allowances (cap and trade) is not economic but political. With a tax, firms must pay the government for each ton of pollutant that they emit. With tradeable allowances, firms must either use the allowances that they are given or, if they want to emit more, they must buy allowances from other firms. Either way, firms that are given allowances in the initial allocation get a big benefit compared with having to pay taxes. Thus, some people say that allowances equal corrective taxes plus corporate welfare. That's not necessarily the best way of looking at the issue, however. First, allowances need not be given away; they could be auctioned to the highest bidder, as under some proposed tradeable allowance programs for carbon dioxide this would also raise significant tax revenue. Making progress against global warming, moreover, may require building a political coalition. A carbon tax pushes one very powerful and interested group, the large energy firms, into the opposition. If tradeable allowances are instead given to firms initially, there is a better chance of bringing the large energy firms into the coalition.

US-10-m

238

Can the misuse of a common resource be foreseen and prevented? If predictions of rapid global warming are correct, our analysis points to a number of solutions to minimize the tragedy of the commons. Businesses and individuals can be discouraged from producing emissions through carbon pricing, which charges firms by the ton for the CO2, they put into the atmosphere. This policy encourages parties to internalize the negative externality, because carbon pricing acts as an internal cost that must be considered before creating carbon pollution. Another solution, known as cap and trade, is an approach to emissions reduction that has received much attention lately. The idea behind cap and trade policy is to encourage carbon producers to internalize the externality by establishing markets for tradable emissions permits.

238-239

As a result, a profit motive is created for some firms to purchase, and others to sell, emissions permits. Under cap and trade, the government sets a cap, or limit, on the amount of CO2, that can be emitted. Businesses and individuals are then issued permits to emit a certain amount of carbon each year. Also, permit owners may trade permits. In other words, companies that produce fewer carbon emissions can sell the permits they do not use. By establishing property rights that control emissions permits, cap and trade causes firms to internalize externalities and to seek out methods that lower emissions. Global warming is an incredibly complex process, but cap and trade policy is one tangible step that minimizes free-riding, creates incentives for action, and promotes a socially efficient outcome. Cap and trade is a good idea, but there are issues that must be overcome to make it work effectively. For example, cap and trade presumes that nations can agree on and enforce emissions limits, but international agreements have proved difficult to negotiate. Without binding international agreements, nations that adopt cap and trade policies will experience higher production costs, while nations that ignore them - and free-ride in the process - will benefit.

US-11-m

364-365

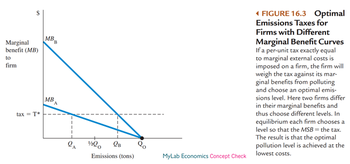

[0 and A are originally in subscript in Q0, 2Q0, 1⁄2Q0, Qa]

Emission taxes will work much better in this regard. Suppose in drawing the marginal social benefit curve in Figure 16.2 we were combining information from two different polluters. One firm, A, finds it easy to avoid polluting. Perhaps it is a new plant, easily able to switch to a different type of fuel. For A, the marginal benefit of polluting is relatively low because avoiding that pollution is easy. A second firm, B, is old and can stop polluting only at great expense. Ideally, if we want to reduce as much pollution as possible per dollar, we should have the firm that can reduce pollution cheaply do more of it. That is exactly what a tax will do. If the government sets a tax at $10 per ton of carbon emitted, both firms will take actions that reduce carbon as long as those actions cost them less than $10 per ton. For Firm A, there may be many such actions, so it will cut back a lot before it becomes too expensive to do any more. For Firm B, perhaps little reduction will occur. Both firms will look across technological solutions to find the ones that reduce emissions at the lowest costs. In the end, the key policy goal is to make sure the right amount of total reduction occurs, and taxes will accomplish this at lower costs than will a standard.

Figure 16.3 shows us how a tax would work for Firms A and B. Before we impose a tax, each firm is polluting at its maximum level, thinking of pollution as free. Each firm produces Q0 worth of emissions. Total industry emissions are thus 2Q0. Suppose now the government, based on information about both firms and about the MSCs of emissions, wants to cut emissions in half to Q0. Looking at the information it has gathered, it sets the tax at T*. Every unit of emissions produced by the firm costs it T*, so you can think of T* as the per-unit price of emissions.

Look first at Firm A. At its original level of emissions, Q0, the tax per unit is quite a bit higher than the marginal benefit it gets from polluting. So it starts to cut back using whatever technological opportunities it has. As long as the price of the emission is more than the benefit to the firm of not cleaning up, the firm reduces its emissions. For firm A, emissions fall all the way to QA. At that point, it is too expensive to cut back any further. Firm B, with much higher benefits from polluting, ends up producing QB emissions. If the tax has been set right, the sum of QA and QB will be Q0, or one half the original emission level of 2Q0. The tax has accomplished its task of reducing emission levels.

Suppose we had instead used standards to achieve the emissions reduction, requiring each firm to produce 1⁄2Q0 rather than allowing firms to choose emissions based on their costs. Firm B is now producing more emissions than the standards would have required and would need to reduce further. We can see from the marginal benefit curve of Firm B how much it would lose by having to cut back its emissions further. Firm A’s emissions under the tax system are lower than 1⁄2Q0, the standard allowance, so Firm A could increase its emissions. So a common standard benefits Firm A and costs Firm B. Notice, Firm A gains less from the ability to have higher emissions than Firm B loses in having to reduce its emissions. Therefore, on net, using a standard to achieve the desired emissions level gives us higher costs. The emissions tax has not only reduced emissions as firms face the true price of those emissions, but it has also done so at minimum cost by encouraging firms with the lower benefits from polluting to do less of it relative to other firms.

The control of carbon emissions is one area in which many economists have argued strongly for the use of a tax, though we have not yet seen one at the federal level. Carbon emissions come from many different industries and consumers, with different marginal social benefit curves. Automobiles and airplanes create considerable emissions; power plants also emit considerable carbon. Moreover, each of these actors has multiple ways to reduce emissions, from fuel choice to filters to technology choice. As we have seen, with big differences in marginal benefit curves taxes can achieve the same results as standards but at lower costs.

366

Carbon pricing initiatives have been implemented in 45 nations and 25 subnational jurisdictions. These initiatives increased from 29 in 2015 to 51 in 2018. Carbon pricing initiatives comprise of 25 emission trading systems (ETSs) and 26 national carbon taxes. These carbon pricing initiatives — that were implemented or scheduled for implementation — accounted for 11 gigatons of carbon dioxide emissions or about 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The aggregate value of the ETSs and carbon taxes in 2018 reached $82 billion. Between 2017 and 2018, carbon pricing increased by 56 percent, mostly in Latin America and Asia. But these initiatives still fall short of the 2020 temperature reduction target. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the EU has implemented reforms that raised the price of carbon allowances from €4.38 per ton in May 2017 to €13.82 per ton in 2018. In order to achieve the target of limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, carbon allowances have to be priced at €25–€30 per ton by 2020–2021 and to quadruple by 2030. But these initiatives will not suffice because there are many nations and jurisdictions round the world that are lagging behind. These countries can adopt indirect policies such as imposing fuel taxes, the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, and regulations that may incorporate a “social cost of carbon.”

367-368

Europe implemented the world’s first mandatory trading scheme for carbon dioxide emissions in 2005 in response to its concern for global warming. Carbon dioxide emissions are a major source of global warming. The first phase of the plan, which was over at the end of 2007, involved around 12,000 factories and other facilities. The participating firms were oil refineries; power generation facilities; and glass, steel, ceramics, lime, paper, and chemical factories. These 12,000 plants represented 45 percent of total European Union (EU) emissions. The EU set an absolute cap on carbon dioxide emissions and then allocated allowances to governments. The nations in turn distributed the allowances to the separate plants. In the second phase from 2008 through 2012, a number of large sectors were added, including agriculture and petrochemicals. In both the United States and Europe, the allowances are given out to the selected plants free of charge even though the allowances will trade at a high price once they are distributed. Many are now questioning whether the government should sell them in the market or collect a fee from the firms. As it is, many of the firms that receive the allocations get a huge windfall. During the second phase in Europe, the governments are allowed to auction more than 10 percent of the allowances issued.

US-12-m

198-199

(Source: Chicago Tribune, July 3, 2018.)

The idea is to impose a tax on carbon dioxide emissions, starting at $40 per ton and gradually increasing. That would raise the price of a gallon of gasoline by about 38 cents. The tax would foster conservation, make alternative energy sources such as solar and nuclear power more competitive, and give consumers and companies time to adapt without painful disruptions. Economists generally agree that a levy of this type would produce the most benefit for the least cost.

199

(Source: Chicago Tribune, July 3, 2018.)

They [Climate Leadership Council, a group featuring such GOP stalwarts George Schultz and N. Gregory Mankiw.] want to rebate the money to citizens as “carbon dividends”—which would amount to about $2,000 per family of four at the start. All the revenue would be returned to the public. Why collect money only to give it back? The intent is to change consumer behavior when it comes to energy use without creating a pot of money for elected officials to squander. Individuals who conserve would come out ahead, while those who drive gas-guzzlers with abandon would pay in more than they get back. In this scenario, the tax would also replace the current regulations on emissions and energy use, dramatically reducing the role of government bureaucrats. “Less government, less pollution” is the theme.

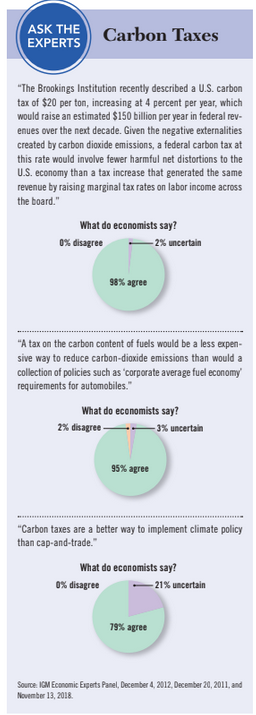

200

Figure on experts opinions

US-13-m

84

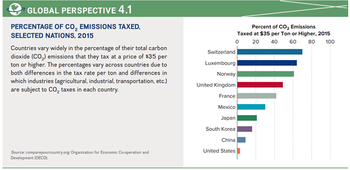

Figure 4.1

91

The trick for government, then, is to figure out how to achieve the allocatively efficient output level at the lowest possible cost. As you know from this chapter, that can be accomplished by figuring out the marginal cost of pollution abatement for each source of pollution and comparing it with the marginal benefit associated with mitigating that source of pollution. The government should then take steps to shut down all the polluting activities for which the marginal benefit of abatement exceeds the marginal cost of abatement. That’s a great strategy, but can the government implement it? The answer is yes, but the government needs to overcome an important obstacle. The costs of pollution abatement are not obvious. Would it, for instance, be less costly to eliminate 1 million tons per year of CO2 emissions by shutting down a small factory in Memphis or by paying to retire highly inefficient older vehicles in Denver? To the extent those costs are known, they are often known to the emitters themselves, but not to the government. The government therefore encounters an asymmetric information problem. How can it reduce pollution at the lowest cost when it is the polluters themselves that are the only ones likely to know what those costs are?

Tradeable emissions permits (“cap and trade”) are another way to overcome the asymmetric information problem. These work by giving polluters a financial incentive to reveal their emission reduction costs and, better yet, follow through on emissions reductions. Suppose the U.S. government knows that the allocatively optimal amount of CO2 emissions is 4 billion tons per year, but that 5 billion tons are currently being emitted. The government will cap the total amount of emissions by printing up and handing out to polluters only 4 billion tons’ worth of tradable emissions permits. Each permit may be for, say, 1 ton of CO2 emissions, and emitting that amount of CO2 is legal only if you have a permit. The government will have to hand out the permits without knowing whether they are going to the emitters that have the lowest costs of abatement. But then the government can let the invisible hand do its work. The permits are tradeable, meaning that they can be bought and sold freely. An emissions-trading market will pop up and what you’ll find is that the firms with the highest costs of emissions reduction will purchase permits away from the firms with the lowest costs of emission reduction. The high-cost firms benefit because it is less expensive for them to buy permits to keep on polluting than it is to reduce their own pollution. And the low-cost firms benefit because they can make more money selling their permits than it will cost them to reduce their emissions (which they must do after they sell away their permits). Both sides win, the externality is reduced at the lowest cost, and society achieves the allocatively efficient level of pollution. Tradeable pollution permits have worked successfully in several regions for several different types of emissions. They are an economically sophisticated way of overcoming the asymmetric information problem in pollution abatement in order to reduce emissions at the lowest possible cost.

373

The vast majority of consumers won’t know that an emissions trading permit system even exists. They will only see that the price of biodiesel looks much lower. But that lower price will provide them with a stronger incentive to switch from oil to biodiesel any time the price of oil rises above $55 per barrel.

US-14-m

451 -455

[1, 2 are originally in subscript in x1, x2, c1, c2, x̄1, x̄2, MC1, MC2. x1,x2 are originally in subscript in min(x1,x2), minx1]

Motivated by concerns about global warming, several climatologists have urged governments to institute policies to reduce carbon emissions. Two of these reduction policies are particularly interesting from an economic point of view: carbon taxes and cap and trade. A carbon tax imposes a tax on carbon emissions, while a cap and trade system grants licenses to emit carbon that can be traded on an organized market. To see how these systems compare, let us examine a simple model.

Optimal Production of Emissions

We begin by examining the problem of producing a target amount of emissions in the least costly way. Suppose that there are two firms that have current levels of carbon emissions denoted by (x̄1, x̄2). Firm i can reduce its level of emissions by xi at a cost of ci(xi). Figure 24.10 shows a possible shape for this cost function. The goal is to reduce emissions by some target amount, T, in the least costly way. This minimization problem can be written as

c1(x1) + c2(x2)

such that x1 + x2 = T.

If it knew the cost functions, the government could, in principle, solve this optimization problem and assign a specific amount of emission reductions to each firm. However, this is impractical if there are thousands of carbon emitters. The challenge is to find a decentralized, market-based way of achieving the optimal solution. Let us examine the structure of the optimization problem. It is clear that at the optimal solution the marginal cost of reducing emissions must be the same for each firm. Otherwise it would pay to increase emissions in the firm with the lower marginal cost and decrease emissions in the firm with the higher marginal cost. This would keep the total output at the target level while reducing costs.

Hence we have a simple principle: at the optimal solution, the marginal cost of emissions reduction should be the same for every firm. In the two-firm case we are examining, we can find this optimal point using a simple diagram. Let MC1(x1) be the marginal cost of reducing emissions by x1 for firm 1 and write the marginal cost of emission-reduction for firm 2 as a function of firm 1’s output: MC2(T − x1), assuming the target is met. We plot these two curves in Figure 24.11. The point where they intersect determines the optimal division of emission reductions between the two firms given that T emission reductions are to be produced in total.

A carbon Tax

Instead of solving for the cost-minimizing solution directly, let us instead consider a decentralized solution using a carbon tax. In this framework, the government sets a tax rate t that it charges for carbon emissions. If firm 1 starts with x̄1 and reduces its emissions by x1, then it ends up with x̄ 1 − x1 emissions. If it pays t per unit emitted, its carbon tax bill would be t(x̄ 1 − x1).

Faced with this tax, firm 1 would want to choose that level of emission reductions that minimized its total cost of operation: the cost of reducing emissions plus the cost of paying the carbon tax on the emissions that remain. This leads to the cost minimization problem

minx1 c1(x1) + t(x̄1 – x1).

Clearly the firm will want to reduce emissions up to the point where the marginal cost of further reductions just equals the carbon tax, i.e., where t = MC1(x1). If the carbon tax is set to be the rate t*, as determined in Figure 24.11, then the total amount of carbon emissions will be the targeted amount, T. Thus the carbon tax gives a decentralized way to achieve the optimal outcome.

Cap and Trade

Suppose, alternatively that there is no carbon tax, but that the government issues tradable emissions licenses. Each license allows the firm that holds it to produce a certain amount of carbon emissions. The government chooses the number of emissions licenses to achieve the target reduction. We imagine a market in these licenses so each firm can buy a license to emit x units of carbon at a price of p per unit. The cost to firm 1 of reducing its emissions by x1 is c1(x1) + p(x̄1 – x1). Clearly the firm will want to operate where the price of an emissions license equals the marginal cost, p = MC1(x1). That is, it will choose the level of emissions at the point where the cost of reducing carbon emissions by one unit would just equal the cost saved by not having to purchase a license. Hence the marginal cost curve gives us the supply of emissions as a function of the price. The equilibrium price is the price where the total supply of emissions equals the target amount T. The associated price is the same as the optimal carbon tax rate t∗ in Figure 24.11.

The question that remains is how to distribute the licenses. One way would be to have the government sell the licenses to firms. This is essentially the same as the carbon tax system. The government could pick a price and sell however many licenses are demanded at that price. Alternatively, it could pick a target level of emissions and auction off permits, letting the firms themselves determine a price. This is one type of “cap and trade” system. Both of these policies should lead to essentially the same market-clearing price.

Another possibility would be for the government to hand out the licenses to the firms according to some formula. This formula could be based on a variety of criteria, but presumably an important reason to award these valuable permits would be building political support for the program. Permits might be handed out based on objective criteria, such as which firms have the most employees, or they might be handed out based on which firms have donated the most to some political causes.

From the economic point of view, it doesn’t matter whether the government owns the licenses and sells them to the firms (which is basically a carbon tax system) or whether the firms are given the licenses and sell them to each other (which is basically cap and trade).

If a cap and trade system is created, firms will find it attractive to invest in ways to acquire the emission permits. For example, they would want to lobby Congress for such licenses. These lobbying expenditures should be counted as part of the cost of the system, as described in our earlier discussion of rent seeking. Of course, the carbon tax system would also be subject to similar lobbying. Firms would undoubtedly seek special carbon tax exemptions for one reason or another, but it has been argued that the carbon tax system is less susceptible to political manipulation than a cap and trade system.

US-15-m

611

It is the way some people advocate the world could confront the problem of carbon pollution and climate change — rather than imposing a carbon tax, nations could agree to a global cap requiring permits that could then trade on the open market.

US-16-m

45

Examples are banning lead in petrol (gasoline) or issuing a limited number of permits to emit CO2 and allowing firms to buy and sell these permits. Without regulation, electricity generators do not pay for using up the absorptive capacity of the biosphere. By limiting the total number of permits issued, this policy limits the total amount of emissions and puts a price on the use of CO2 because firms emitting it have to buy permits. This also provides a profit motive for owners of firms to reduce carbon emissions that is absent when they are not regulated. These policies protect the environment by making goods produced in environmentally harmful ways either illegal or costly, so they will be used less.

431

Carbon taxes are an important tool for tackling climate change; in this case, the aim is unambiguously to reduce green house gas emissions.

433

If the government’s objective is to reduce the consumption of a good that is considered harmful—like tobacco or carbon—the tax will be more effective if demand is elastic so that quantity falls substantially.

US-10-M

84

Figure 4.1

91

The trick for government, then, is to figure out how to achieve the allocatively efficient output level at the lowest possible cost. As you know from this chapter, that can be accomplished by figuring out the marginal cost of pollution abatement for each source of pollution and comparing it with the marginal benefit associated with mitigating that source of pollution. The government should then take steps to shut down all the polluting activities for which the marginal benefit of abatement exceeds the marginal cost of abatement. That’s a great strategy, but can the government implement it? The answer is yes, but the government needs to overcome an important obstacle. The costs of pollution abatement are not obvious. Would it, for instance, be less costly to eliminate 1 million tons per year of CO2 emissions by shutting down a small factory in Memphis or by paying to retire highly inefficient older vehicles in Denver? To the extent those costs are known, they are often known to the emitters themselves, but not to the government. The government therefore encounters an asymmetric information problem. How can it reduce pollution at the lowest cost when it is the polluters themselves that are the only ones likely to know what those costs are?

Tradeable emissions permits (“cap and trade”) are another way to overcome the asymmetric information problem. These work by giving polluters a financial incentive to reveal their emission reduction costs and, better yet, follow through on emissions reductions. Suppose the U.S. government knows that the allocatively optimal amount of CO2 emissions is 4 billion tons per year, but that 5 billion tons are currently being emitted. The government will cap the total amount of emissions by printing up and handing out to polluters only 4 billion tons’ worth of tradable emissions permits. Each permit may be for, say, 1 ton of CO2 emissions, and emitting that amount of CO2 is legal only if you have a permit. The government will have to hand out the permits without knowing whether they are going to the emitters that have the lowest costs of abatement. But then the government can let the invisible hand do its work. The permits are tradeable, meaning that they can be bought and sold freely. An emissions-trading market will pop up and what you’ll find is that the firms with the highest costs of emissions reduction will purchase permits away from the firms with the lowest costs of emission reduction. The high-cost firms benefit because it is less expensive for them to buy permits to keep on polluting than it is to reduce their own pollution. And the low-cost firms benefit because they can make more money selling their permits than it will cost them to reduce their emissions (which they must do after they sell away their permits). Both sides win, the externality is reduced at the lowest cost, and society achieves the allocatively efficient level of pollution. Tradeable pollution permits have worked successfully in several regions for several different types of emissions. They are an economically sophisticated way of overcoming the asymmetric information problem in pollution abatement in order to reduce emissions at the lowest possible cost.

FR-1-m

376

Une solution consiste à distribuer à chacun des « droits à polluer » par exemple, des droits à déverser tant de CO2 dans l’atmosphère.

FR-2-m

299

Pour ce qui concerne le problème de la pollution, il reste à savoir dans quel cas on se trouve quant aux pentes relatives du coût marginal et du bénéfice marginal. Pour cela, il convient de se tourner vers les études empiriques. […] Ces simulations [Pizer 2002] (qu'il convient certes de prendre avec beaucoup de prudence) montrent qu'on est clairement dans le cas où la pente de la courbe de coût marginal est (beaucoup) plus forte que la pente de la courbe de bénéfice marginal. Selon l'approche de Weitzman, c'est donc la taxe et non les permis qui serait l'instrument de régulation le plus efficace pour ce qui concerne les émissions de dioxyde de carbone.

[...]

Les résultats précédents expliquent pourquoi de nombreux économistes de l'environnement, à commencer par les deux plus célèbres d'entre eux, les Américains William Nordhaus et Martin Weitzman, affichent clairement leur préférence pour une taxe carbone harmonisée au niveau mondial par rapport à l'instrument du marché des PEN préconisé par le protocole de Kyoto. Nordhaus fait d'ailleurs preuve d'un certain scepticisme à l'égard des systèmes de quotas (marchés des permis), notamment en raison de leur complexité, des coûts de transaction élevés qu'ils impliquent et du risque important d'instabilité, les permis pouvant être considérés, selon lui, comme l'équivalent pour le climat des produits dérivés de la finance !

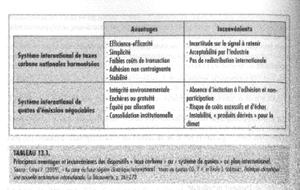

D'une manière synthétique, les avantages et les inconvénients des deux instruments sont récapitulés dans le Tableau 13.1.

300-301

En Europe, il est clair que le marché du carbone n'a pas rempli toutes ses promesses. Dans la lignée du protocole de Kyoto, il s'agissait d'augmenter le prix du carbone et d'inciter les entreprises à innover dans des procédés moins polluants en développant un système européen d'échange de quotas de CO2, (système EUETS pour European Union Emission Trading System). Ainsi, les entreprises des secteurs de l'électricité, du ciment, de la sidérurgie, du papier, des engrais, ou les compagnies aériennes doivent acquérir des permis pour pouvoir émettre du CO2, dans le cadre de leurs activités. Un nombre global de quotas avait été décidé au niveau européen. Les États membres se les sont partagés et les ont distribués gratuitement aux entreprises. En 2005, lors du lancement de la première phase, la Commission européenne avait table sur un cours de la tonne de CO2, aux alentours de 30 €, un prix jugé suffisamment élevé pour être incitatif. Mais le cours s'est rapidement effondré, notamment parce que trop de permis avaient été émis (excès d'offre). La deuxième phase s'est déroulée de 2008 à 2012. De nouveau, le cours de la tonne de CO2 s'est rapidement effondré, notamment en raison de la crise économique qui a provoqué une baisse globale de l'activité des entreprises et donc une diminution de la demande de permis. Certains économistes restent convaincus de l'intérêt de mettre en place un système international de quotas d'émission négociables. Ils nuancent les critiques adressées au marché européen du carbone en arguant qu'il y a toujours une phase de tâtonnement dans la mise en place d'un nouvel instrument de régulation. Par ailleurs, ils font remarquer que les coûts liés à la pollution et les impacts du changement climatique sont sans cesse réévalués à la hausse, avec la mise en avant de risques majeurs (effets de seuil, irréversibilités, etc.). Dans ce cas, on sort du domaine du risque quantifiable pour entrer dans celui de l'incertitude radicale. Si tel est le cas, l'application stricte du principe de précaution doit se substituer à l'analyse coût-bénéfice traditionnelle. Or, les instruments de régulation basés sur les quantités, comme les permis négociables, permettent de fixer des objectifs quantitatifs précis. D'autres économistes, dans la lignée de Nordhaus (cf. ci dessous), affirment cependant que l'on fait fausse route avec les systèmes de permis et préconisent au contraire une taxe carbone harmonisée au niveau mondial.

301

TAXE OU PERMIS: LE POINT DE VUE DE W. NORDHAUS [2009]

Dans sa conférence sur les enjeux économiques du climat donnée à Copenhague en 2009 William Nordhaus commente le problème du manque de recul sur l'approche par les permis (approche appelée "cap-and-trade" dans la citation), en faisant un parallèle saisissant avec l'utilisation d'armes par les militaires « Just as it would be dangerous for military planners to use a completely untested weapon to defend against grave threats, it would be similarly perilous for the international community to rely on an untested system like international cap-and-trade to prevent climate change. »

Nordhaus W. (2009) "Economic Issues in Designing a Global Agreement on Global Warming communication à la conference Climate Change Global Risks. Challenges and Decisions, Copenhague 10-12 mars.

[...]

Une position plus nuancée consisterait à mettre en avant les avantages de chaque instrument et d'en rechercher la complémentarité. Il s'agirait alors de poursuivre la construction d'un système international de quotas, avec un véritable marché mondial du carbone, sans pour autant abandonner tout système de taxe. On peut imaginer une architecture à plusieurs niveaux, avec un système de permis au niveau mondial et un système de taxes au plan national.

FR-3-m

329

Le prix d’échange des permis est déterminé sur le marché des permis. C’est le principe de base du marché carbone européen.

330

La taxe carbone, votée en 2013, constitue-t-elle un nouvel impôt ?

À la différence de la « contribution climat-énergie » qu’avaient tenté de mettre en place de précédents gouvernements, il ne s’agit pas à proprement parler d’un nouvel impôt, mais d’un changement de calcul d’impôts existants : les taxes intérieures sur la consommation de produits énergétiques. Depuis le 1er janvier 2014, une composante carbone a été introduite dans le barème du calcul de cet impôt, au prorata de la quantité de CO2 qui est émise lors de la consommation de chaque énergie. La Loi de Finances prévoit une montée en charge progressive de cette composante, avec un tarif qui démarre à 7 € par tonne de CO2 en 2014 pour arriver à 22 € en 2016.

Qui va la payer ?

Tous les assujettis aux taxes existantes qui utiliseront des énergies fossiles émettrices de CO2 . Si on se réfère aux consommations énergétiques historiques, les ménages devraient régler un peu plus de la moitié de cette taxe, principalement sous forme de carburants pour se déplacer et d’achat de gaz et de fioul domestique pour les usages domestiques. Cette taxe représentera en moyenne 98 euros par ménage en 2016. Les entreprises de production d’électricité et les secteurs industriels très intenses en énergie ne sont pas assujettis aux taxes intérieures sur l’énergie. Ce sont majoritairement les entreprises de service et de l’industrie légère qui régleront, avec les administrations, le reste de la taxe carbone.

À votre avis, comment devraient être redistribuées les recettes de cette taxe ?

Une idée intuitive est d’affecter le produit de la taxe carbone au financement de la transition énergétique. D’une façon générale, beaucoup de nos concitoyens souhaiteraient que les taxes écologiques financent des actions de protection de notre environnement. Au plan macroéconomique, une telle utilisation n’est pas optimale. Il est plus efficace d’utiliser le produit de cette taxe pour baisser d’autres charges pesant sur les facteurs de production. on peut ainsi obtenir un second dividende, de nature économique. Socialement, il faut aussi prévoir des filets de sécurité sous forme de compensation forfaitaire pour éviter d’accroître la précarité énergétique des ménages les plus vulnérables.

FR-4-m

226

Pour pouvoir comparer de multiples externalités, il est nécessaire de bâtir des indicateurs ayant une portée plus générale. C’est tout l’intérêt par exemple de l’estimation de la valeur tutélaire du carbone, qui désigne le prix, fixé par la puissance publique, d’une tonne de gaz carbonique émis en fonction de son effet potentiel à long terme sur l’environnement, quelle que soit sa source. Sa détermination fait l’objet de débats au sein du monde scientifique, car il est très complexe d’estimer l’effet moyen de l’émission d’une tonne de carbone sur le réchauffement climatique et par là, sur l’environnement. Une fois déterminée la « valeur tutélaire du carbone », les externalités liées à la pollution ou à l’utilisation d’énergie peuvent être ramenées à leur équivalent en émission de gaz carbonique. Si par exemple une usine rejette un million de tonnes de gaz carbonique par an, et que sa valeur tutélaire est de 32 €, comme le préconisait le rapport de la Commission Quinet en 2009 , alors on peut estimer le coût de l’externalité liée à la pollution à 32 millions d’euros. La valeur tutélaire du carbone est vouée à augmenter progressivement, de façon à inciter à la diminution des émissions de carbone, de façon progressive afin de rendre l’évolution acceptable, avec un horizon d’une taxe fixée autour de 100 € la tonne en 2030, référence retenue jusqu’à présent. Ce mécanisme permet de mener une politique environnementale cohérente quelle que soit la source de pollution ou de consommation d’énergie, en attribuant toujours la même valeur à une quantité donnée de pollution. Cependant, il n’y a pas de consensus aujourd’hui pour fixer la valeur tutélaire du carbone, dont la progressivité fait débat, et les autorités politiques rencontrent généralement des difficultés pour imposer à leur opinion publique une valeur tutélaire conforme aux préconisations des experts.

249

Au lieu d’imposer à chaque agent un quota individuel d’émission polluante, la puissance publique défini au niveau global un volume maximal de pollution, par exemple 10 000 tonnes d’émissions de carbone par an. En fonction de cet objectif, elle va créer des droits d’émission, par exemple 10 000 titres donnant chacun l’autorisation d’émettre 1 tonne de carbone par an. Une entreprise qui désire émettre 30 tonnes de carbone par an doit impérativement posséder 30 titres. L’État peut initialement donner ou vendre ces titres aux entreprises, dans les deux cas elles sont en mesure de les vendre entre elles sur un marché, dit marchés de quotas. Supposons que le prix d’un titre d’une tonne d’émission de carbone se fixe à 100 euros. Les entreprises achètent un titre si le coût de réduction de ses émissions d’une tonne de carbone est supérieur à 100 euros. Sinon, l’entreprise a intérêt à modifier ces techniques de production afin de réduire sa pollution et d’économiser le coût d’achat d’un titre. Les entreprises qui possèdent des titres vont les revendre si leur prix est supérieur au coût de réduction d’une tonne de pollution. En fonction des coûts de dépollution de chaque entreprise, le prix du titre va se fixer plus ou moins haut. L’objectif de pollution va être atteint à moindre coût car au final les entreprises pour lesquelles les coûts de dépollution sont faibles vont plutôt choisir de dépolluer plutôt que d’acheter des titres alors que celles qui subissent des coûts élevés de dépollution vont chercher à acquérir des quotas d’émission. Cette solution semble plus efficace qu’un système de quotas individuels. Si le marché des quotas est ouvert à tous les acteurs (et pas seulement réservé aux entreprises polluantes), les individus qui désirent voir le niveau de pollution diminuer peuvent acheter des titres afin de les stocker et réduire le niveau global de pollution. Il est ainsi possible d’imaginer qu’une association écologique retire 1 000 titres du marché afin de faire porter à 9 000 le nombre de tonnes de carbone émises par an. En faisant cela, elle révèle la valeur de sa préférence pour l’environnement. Dans un tel cas de figure, le mécanisme du marché conduit le prix à se fixer de façon telle que la pollution se situe à son niveau optimal.

250

De tels systèmes sont déjà à l’œuvre, comme le marché européen du carbone, créé en 2005 mais sont généralement réservés aux entreprises polluantes. Le marché européen du carbone a connu des vicissitudes importantes (LAURENT, CACHEUX, 2015). Une partie des problèmes vient du fait que les titres ont été initialement émis en trop grand nombre, ce qui a eu pour conséquence un prix trop faible de la tonne de carbone n’incitant pas les entreprises à réduire leurs émissions. Par ailleurs, ces marchés sont souvent caractérisés par une instabilité endogène, les comportements spéculatifs et les anticipations des agents conduisant à de fortes variations des cours qui peuvent perturber le bon fonctionnement du marché, et sa capacité à fixer les prix permettant d’atteindre le niveau optimal de pollution. Notons toutefois qu’il est possible de limiter ces fluctuations en régulant le fonctionnement du marché, comme en imposant par exemple un prix plancher et un prix plafond au prix du carbone.

FR-5-m

280

Au sommet sur le changement climatique qui s'est tenu à Kyoto en 1997, les participants ont initié une réflexion sur l'utilisation de marchés de « droits à polluer ».

FR-4-M

311

Les économistes s'accordent largement à considérer que la meilleure politique est de fixer un prix sur les émissions de carbone (par exemple sous la forme d'une taxe carbone), afin d'internaliser l'externalité associée à ces émissions.

En l'absence d'un tel accord, l'économiste William Nordhaus, de l'université de Yale, a proposé une solution : les pays volontaires pour adopter une taxe carbone devraient le faire et imposer des droits de douanes sur les biens importés en provenance de pays qui ne le font pas. Cela pourrait inciter l'ensemble des pays à adopter la taxe carbone.

312

La meilleure politique serait l'introduction d'une taxe carbone, mais celle-ci se heurte à des obstacles politiques et géopolitiques.

FR-7-M

53

Pour contrer le réchauffement climatique, les gouvernements de différents pays sont amenés à mettre en place des réglementations strictes sur les émissions de carbone. Ces réglementations- quotas d'émissions, taxes carbone, interdiction de certaines activités - peuvent également conduire à une baisse de la productivité qui réduit les perspectives de croissance. En conséquence, tant l'inaction que l'action vis-à-vis du réchauffement climatique peuvent conduire à limiter la croissance économique sur le long terme.

55

Le deuxième piller utilisé par de nombreux gouvernements consiste à mettre en place des mécanismes de marché incitant les acteurs à réduire leurs émissions et leur consommation de ressources fossiles. Les entreprises sont motivées par le profit, et réalisent donc les optimisations nécessaires pour augmenter leurs revenus et réduire leurs coûts. Des subventions - côté revenu et des taxes - côté coût liées au respect ou non de certaines pratiques peut inciter les acteurs à intégrer les facteurs environnementaux dans leur prise de décision. C'est notamment le principe de la taxe carbone. Si nous pensons qu'une tonne de carbone émise dans l'atmosphère coûte à l'humanité 200 euros, taxer les entreprises à hauteur de 200 euros par tonne de carbone les incitera à n'émettre des gaz à effet de serre que dans le cas où ces émissions sont vraiment essentielles, et rapportent à la société plus que les 200 euros qu'elles ne lui coûte. L'Union Européenne a mis en place un système similaire basé sur des quotas d'émission que les entreprises des secteurs régulés doivent acheter à hauteur de leur pollution annuelle. Au lieu de spécifier un prix du carbone, elle cible une quantité de gaz à effet de serre que les entreprises ont le droit d'émettre, et les prix s'ajustent pour que cette quantité soit atteinte en sélectionnant les usages les plus utiles.

157

La création d'un marché du Carbonne pour internaliser les coûts de pollution aux fonctions de prix des entreprises. Ce mécanisme a été adopté par l'Union Européenne suite à la signature des accords de Kyoto en 1997 visant à la réduction de 5% des émissions de CO2, entre 2008 et 2012.

FR-2-B

160

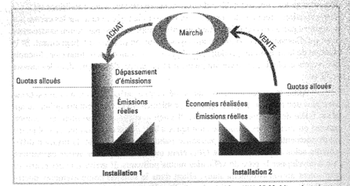

Cette autre solution à la pollution est la création de marchés de « droits à polluer ». L'idée en est simple. Plutôt que de faire payer une taxe à l'entreprise qui émet du CO2, par exemple, taxe dont on ne sait pas si elle va être vraiment optimale. mieux vaut lui accorder un permis d'émission qu'elle pourra vendre sur un marché à une autre entreprise. Cette solution est plus conforme aux canons de l'analyse économique libérale, car le prix sur le marché est le résultat de calculs rationnels alors que la taxe est le résultat d'une décision administrative. En particulier, on laisse le choix à l'entreprise de payer pour polluer ou faire les frais nécessaires pour éviter d'avoir à acquérir ce droit. Dans ce second cas, elle peut revendre à une autre entreprise le droit dont elle n'a plus besoin. La figure 6.10 montre ce mécanisme : l'installation 2 a intérêt à faire les travaux lui permettant de limiter ses émissions de gaz, car le prix auquel elle va vendre le droit qu'elle possède est plus élevé que le coût de ces travaux. L'installation 1 va tenir un raisonnement identique qui aboutit au résultat inverse, à savoir qu'elle a intérêt à acheter le droit de polluer, car cela lui coûte moins que d'entreprendre des travaux. Si beaucoup d'entreprises sont dans la situation de l'installation 1, alors il y aura beaucoup plus d'acheteurs que de vendeurs et le prix du droit à polluer va augmenter. Cela va accroître l'intérêt pour certains de changer d'équipements pour moins polluer. Ainsi, contrairement à la taxation, la variation du prix du droit à polluer va orienter les entreprises, selon leur situation, vers la décision la plus profitable, pour elles et pour la société. Cette solution redonne une pertinence à la «main invisible » dans la conduite des comportements pour les orienter vers le choix optimal.

161

Ce que les économistes ont imaginé, les hommes politiques l'ont réalisé, puisque de tels marchés de droits à polluer existent depuis les années 1970 aux États-Unis. Le plus important aujourd'hui est le «marché européen du carbone », créé en 2005 afin que l'Europe atteigne les objectifs de réduction de GES fixés à Kyoto. Sa mise en œuvre est résumée par l'expression anglaise «cap and trade », qui signifie que, dans un premier temps, on doit fixer un quota d'émissions de CO2, et dans un second temps organiser un marché d'échange de ces quotas. Ce sont plus de 11 000 installations qui sont soumises à ces quotas, principalement les producteurs d'énergie, mais aussi le transport, y compris aérien, les cimenteries, les fabricants d'aluminium... La tonne de CO2, vaut entre 10 et 15 € depuis 2010, ce qui semble bon marché par rapport au prix de 32 € qui apparaissait comme efficace dans la lutte contre le réchauffement climatique selon un rapport rédigé en 2009 par Michel Rocard.

Le point essentiel de ces marchés de droits à polluer est qu'ils représentent une forme de privatisation de l'environnement, ce que prônent précisément les économistes libéraux.