Detection in the age of spectacle: the case of Pynchon's "Inherent Vice"

Roberto Andrés Lantadilla

Is it possible to write detective fiction in the postmodern age? Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice shows us masterfully the relevance that the genre still has today.

1. Introduction: a realism of the unreal

2. Failures of detection and aesthetic shocks

3. Inherent Vice and the film noir tradition

4. The pure products of America: California as a land of deception

5. Bibliography

1. Introduction: a realism of the unreal

“Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.” (Chandler, 1944)

“I have lost reality. Can you tell me, please, what is reality?” (Pynchon, 2009)

In his famous essay The Simple Art of Murder (1944), crime writer Raymond Chandler denounces the artificial status of some novels belonging to the detective genre and, by contrast, theorizes the affinity to the real world of crime as the true essence of hard-boiled writing. This characteristic may be also the very reason why the genre still survives throughout the years and the different media: it is not only because of nostalgia, but also due to an eagerness of the genre to interact with the social issues of its era. Because, as Chandler puts it:

“Murder, which is a frustration of the individual and hence a frustration of the race, may have, and in fact has, a good deal of sociological implication.” (Chandler, 1944)

However, some years later something in the relation between reality and fiction changed radically: as a feedback loop, fiction had become more and more self-referential. It is what the critics have labelled as postmodernism, a post-war artistic and cultural movement. The logical consequence of such fictions could be the death of the hardboiled crime novel –if not of the novel itself- as Chandler theorized it, because it would mean a return to that departure from reality of the mystery novel, of the arm-chair detective, that was the very thing these writers were avoiding. In fact, it was Chandler himself in 1950 to write, in an introduction to that same essay, that:

“Within its frame of reference (. . .) a classic is a piece of writing which exhausts the possibilities of its form and can hardly be surpassed.” (Chandler, 1950)

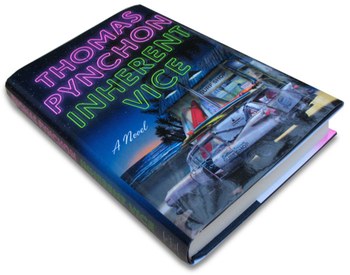

Now we know that his works have achieved such status. Yet his legacy lives on. Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice (2009), his second novel to be set in Southern California and his first to overtly belong to the detective genre, could be seen as a parody of the genre itself, but instead of a postmodern deconstruction, it can be seen just as an update of its themes: it succeeds as an heir of hardboiled realism. From the postmodern point of view it is not reality which affects fiction, but the contrary: and this is something which is at the heart of Inherent Vice, from its very beginning.

In 1967, just as postmodernism was being defied, Guy Debord, radical thinker and one of the founders of the Situationist movement, published his most influential book, The Society of Spectacle. This text proposed the assumption that the images were taking over the real world, and that “everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation” (Debord, 1967: ch.1, I). In this sense, Inherent Vice is a representation of a representation, as it succeeds, as Brian McHale puts it, to show “the way a historical epoch represented itself to itself” (Gold, 2015: p. 209). Thus, it is not a coincidence that the novel itself is preceded by an epigraph which belongs to the Situationist tradition: “Under the paving-stones, the beach!”. It is a graffito commonly found in Paris from a phrase attributed to Debord himself. With Inherent Vice, thus, Pynchon makes use of the hardboiled sensibility as a form of dissent, with strong intertextuality play also with the classic film noir tradition, to witness that paradigm shift which was altering reality in the late sixties and early seventies.

2. Failures of detection and aesthetic shocks

"The story is his adventure in search of a hidden truth (. . .)." (Raymond Chandler, 1944)

“I am, like, overthinking myself into brainfreeze, here.” (Thomas Pynchon, 2009)

In her essay Gumshoe Gothics, Patricia Merivale makes a very interesting point in tracing the roots of both the hardboiled detective story and its postmodern descendent to the same source, The Man of the Crowd by Edgar Allan Poe (Merivale, 1999: 107). From this, we can assume that the very characteristics of the latter were in some manner already present in the classics of the genre, from Dashiell Hammet onwards. Take for example the lack of narrative closure and the failure of detection which Merivale ascribes to the so called "metaphysical detective story" (1999: 102-3): in the hardboiled universe of Chandler, there was already an embodiment of that chaos which belonged to reality. We’re told in fact, that “it is not a very fragrant world, but is the world you live in” (Chandler, 1944). In such a world there has never been an order and, thus, the detective cannot restore it: he just feels powerless in front of it. In fact, in Chandler’s novels Philip Marlowe always arrives too late, when nothing can be done. Then, these hardboiled motifs have evolved into their meta-fictional reflection: this is epitomized by Paul Auster’s City of Glass (1985), which may be read as an essay on detective story writing, or better the impossibility of doing it in the contemporary world:

"In effect, the writer and the detective are interchangeable. The reader sees the world through the detective’s eye, experiencing the proliferation of its details as if for the first time." (Auster, 1987: 8)

However, as we learn from the unravelling of the plot, it’s exactly that “close observation of details” which dooms the detective/writer, leading him to melt “into the walls of the city” (Auster, 1987:p. 117). With this book, Paul Auster wants to draw our attention to what Brian McHale has theorized as a “shift of dominant” in postmodernism, from an epistemological to an ontological, the latter focusing on what Pynchon has called the “intrusions into this world from another” (Pynchon, 1999); namely, the colliding worlds of reality and fiction. Inherent Vice protagonist, the hippie sleuth Doc Sportello, seems to be the ultimate parody of the classic detective: he is constantly accused to suffer from “Doper’s Memory”, and thus presented to be unreliable. Yet he bears various resemblances with Philip Marlowe, the classic hardboiled PI. In fact, about this figure Chandler writes that:

"(. . .) down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid." (Chandler, 1944)

And this is exactly what Doc is in the deceptive, foggy world of Los Angeles in the early seventies: he witnesses the end of the late psychedelic sixties, the dawn of the counterrevolutionary forces, as they all went corrupt by FBI actions such as COINTELPRO, and the emerging of multinational capitalism. But what is unsettling is that no one seemed to notice, as we’re told that people in LA “saw only what they’d all agreed to see” (Pynchon, 2009: 315). Therefore, to say it in Debord’s words, the world of Inherent Vice is one in which:

"The spectacle keeps people in a state of unconsciousness as they pass through practical changes in their conditions of existence." (1967: ch.1, XXV)

In this setting, Thomas Pynchon’s hero Doc Sportello, just as Philip Marlow, has a “range of awareness that startles you” (Chandler, 1944: 992), as they both don’t belong to their times but rather to a nostalgic past - or better put, they don’t belong to any time. This allows them to witness change, and not be carried by it, to “get an unplanned glimpse at the other side”. (Pynchon, 2009: 176).

3. Inherent Vice and the film noir tradition

"It was like seeing John Garfield die for real (. . .)." (Pynchon, 2009)

The film noir ranging from 1947 to 1951 represented an alternative to optimistic Hollywood movies: they were a voice of dissent, often showing the darker sides of the American dream. Take for example what Schader calls the “post-War realistic period from 1945-49” (Schrader, 1972): there were movies such as Force of Evil (1948), starring John Garfield and produced by his own independent production house, which freely attacked corruption and excessive greed. But this golden period was soon to be over, as most of the major figures of these productions were targeted by the HUAC as communists, which put an end to their careers in Hollywood.

In Inherent Vice, Doc Sportello has a fixation with John Garfield: in a scene, before acting, he questions “John Garfield would’ve dealt with the situation” (Pynchon, 2009: 225); in another, he even wears the suit which Garfield wore in The Postman Always Rings Twice (p. 334). And of course, he often cites his movies. This obsession is further confirmation of the moral rectitude of Doc’s character: rather than becoming an informer and reporting communist sympathizers to the HUAC, John Garfield had his career cut short and then even his life. In such fashion, Doc Sportello refuses multiple times to be corrupted by the LAPD and to turn an informant for the FBI infiltration program COINTELPRO. With such actions, the FBI and the government were definitely appropriating the new media: first, with the Hollywood Blacklist of the 50s, voices of dissent were turned down. Then, in the seventies, with the COINTELPRO infiltrations, they started to deceive people by turning reality into a controlled form of fiction. About this matter, Guy Debord writes that the spectacle sole message is: “What appears is good; what is good appears” (1967: ch.1, XII). And it is in this sense that, by taking control of what people saw on TV, the government could control everyday reality: in Inherent Vice, there’s a scene were Doc watches on TV a junkie-turned-snitch yelling at a Nixon rally. When he asks his fiancée, a junior DA, why would they expose an informant like that, she replies that: “Now that he’s been all over TV? He has instant and wide credibility” (Pynchon, 2009: 123). Symptomatic, thus, is a surreal scene near Las Vegas, in which Doc stops at a motel called “TOOBFREEX” famous for its variety of cable channels it receives, where people came deliberately to “bathe in these cathode rays” (ibid.: 253). Here, as a paranormal signal of warning, Doc catches a John Garfield marathon in TV, and specifically watches the end of He Ran All The Way (1951): the last movie to feature him before death caught him a few months later, here John Garfield ends up dead in the gutter. As a sort of ontological coincidence, this fictional scene foresees his death in real life. In the book this scene, as Doc passively watches it, serves to witness the thing we have lost under the influence of spectacle, the “sun that never sets over the empire of modern passivity” (Debord, 1967: ch.1, XIII).

4. The pure products of America: California as a land of deception

"Uptight, city in the smog. Don’t you wish that you could be here too?" (Neil Young, L.A., from Time Fades Away, 1973)

At the beginning of Double Indemnity, both the novel by James M. Cain (1936) and the screen adaption by Billy Wilder (1944), just when we’re introduced to the femme fatal Phyllis, there’s a very exemplary dialogue about her and what she represents in the novel:

“You must be English.” “No, native Californian.” “You don’t see many of them.” (Cain, 2002: 10)

However, as the story progresses, there’s a discrepancy between the book and the movie: in Cain’s novel, Phyllis is the embodiment of the Californian trope of death, something that in the movie is smoldered and only hinted at. Whereas in the novel it is the very characteristic of her madness: "[...] there’s something in me that loves Death. I think of myself as Death, sometimes” (ibid.: p.20). Then Walter Huff, the novel protagonist, after having flirted with death herself, tries to search redemption in the innocent Lola, Phyllis’ stepdaughter. But of course, one cannot retrieve fate from death.

This struggle between life and death is inscribed in the very nature of California itself: on one side you have the ocean, the place where all life comes from, and on the other the desert, its annihilation. As a consequence, fictions set there are impregnated with this dichotomy, assuming apocalyptical tones and character’s willingness to a resignation to fate. In Roman Polanski’s neo-noir Chinatown (1974), for example, these themes are epitomized in the California Water Wars. Here not only the dichotomy is intrinsic in nature, but it’s also pushed forward and taken advantage of by corrupt men: from Robert Towne’s screenplay emerges one of the most corrupt characters of all times, Noah Cross, that when asked by J.J. Gittes what keeps his greed driving, he replies “The future, Mr. Gittes –the future” . In his classic Notes on Film Noir (1972), Paul Schrader defines the main themes of those films as "a passion for the past and present, but also a fear of the future". And it is in this sense that the character Noah Cross appropriates the very essence of life and death in California, that are water and desert, controlling and irremediably altering the future of the land. Therefore, set in the Los Angeles of the forties, Towne’s script “is an eulogy . . . for things lost” (Towne, 1994), and witnessing the change from a detached point of view in the seventies, it serves to denounce the men’s responsibility in that change. And from such an operation descends Inherent Vice. However, being set in the early seventies, it portraits a Los Angeles which was already radically changed. Take for example the classic Californian trope of the Santa Ana Winds: something that was already a mysterious phenomenon, which made “your nerves jump and your skin itch” (Raymond Chandler, Red Wind), in this novel is tinged with the increasing pollution, “with the exhaust from millions of motor vehicles mixing with microfine Mojave sand” (Pynchon, 2009: 98). This human engendered fog is always present in Inherent Vice, and it is one of the multiple deceptive devices that contributes to that:

"great collective dream that everybody was being encouraged to stay tripping around in." (ibid.: 176)

As mentioned above, Pynchon instead writes of the seventies from the detached point of view of the 2000s, denouncing how everything in those years was turning artificial. However, this is a trope which can already be found in some classics of L.A. writing, especially those that take place in Hollywood, the dream factory. Take Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust for example: here from the very beginning we’re introduced to a city which is a patchwork of other styles:

"Mexican ranch houses, Samoan huts, Mediterranean villas, Egyptian and Japanese temples, Swiss chalets, Tudor cottages, and every possible combination of these styles that lined the slope of the canyon." (West, 1939: 3)

This is something that is also present in another great denouncement of the Hollywoodland, The Little Sister by Raymond Chandler. Here, Phillip Marlow, in the middle of an overly complicated case, calls California “the department-store state. The most of everything and the best of nothing.” (Raymond Chandler, 1949: 268) And the consequences, in this heap of copies of other things, is that of a city which turns into a simulacrum, “the identical copy for which no original has never existed” (Jameson, 1984: 66). And this also happens to the people who inhabit it: take for example the novel’s femme fatale, wannabe actress Faye Greener, whose “affectations . . . were so completely artificial that he found them charming” (West, 1939: 59). In a sense she too, as Pyllis, is an embodiment of a Californian trope, and in this case is its self-aware artificiality. Symptomatically, The Day of the Locust ends with a metafictional conflation between reality and fiction: the same scenes which the protagonist fantasized for his painting The Burning of Los Angeles take place among a mass of people waiting in front of a theatre for the celebrities to arrive. Here, the last uncorrupt man is lynched, and his own lynching becomes a spectacle. To put it in Walter Benjamin’s words, mankind’s “self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order” (Benjamin, 1969: 242).

5. Bibliography

Auster Paul, New York Trilogy, 1987.

Benjamin Walter, Illuminations, 1969.

Cain M. James, Double Indemnity, 2002.

Chandler Raymond, Later Novels & Other Writing, 1995.

Chandler Raymond, The Little Sister, 1949.

Chandler Raymond, The Simple Art of Murder, 1944.

Debord Guy, The Society of Spectacle. Chapter 1: Separation Perfected, Bureau of Public Secrets (data di ultima consultazione 20/08/2021).

Gold Eleanor, "Beyond the Fog: Inherent Vice and Thomas Pynchon's Noir Adjustment", in Mercy Cannon e Casey Cothran, New Perspectives on Detective Fiction: Mistery Magnified, 2015.

Hinkson Jake, "At the Center of the Storm: 'He Ran All The Way' and the Hollywood Blacklist", in Noir City Sentinel, 2009, pp.10-11.

Jameson Fredric, "Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism", in New Left Review, n.146, 1984, pp. 53-92.

Maher Stephen. The Lost Counterculture, in Jacobin Mag, 2015 (data di ultima consultazione 20/08/2021).

McHale Brian, From modernism to postmodernism: change of dominant, 1987.

McHale Brian, Postmodernist Fiction, 1987.

Merivale Patricia, "Gumshoe Gothics", in Merivale Patricia e Sweeney Susan Elizabeth, Detecting Texts: The Metaphysical Detective Story from Poe to Postmodernism, 1999, pp. 101-116.

Pynchon Thomas, Inherent Vice, 2009.

Pynchon Thomas, The Crying of Lot 49, 1999.

Schrader Paul, "Notes on Film Noir", in Film Comment, n. 8, 1972, pp. 8-13.

Shaub Thomas Hill, "The Crying of Lot 49 and other California novels", in McHale Brian , Dalsgaard Inger H. e Herman Luc, Cambridge Companion to Thomas Pynchon, 2012, pp. 30-44.

Towne Robert, Chinatown, 1998.

Venturelli Roberto, "Noir e maccartismo", in Ventureli Roberto, L'Età del Noir: Ombre, incubi e delitti nel cinema americano, 1940-60, 2007, pp. 255-295.

Ward Elizabeth e Silver Alain, Raymond Chandler's Los Angeles, 1987.

West Nathanael, The Day of the Locust, 1939.

Foto 1 da Pynchon Wiki (data di ultima consultazione 20/08/2021)

Foto 2 da VICE (data di ultima consultazione 20/08/2021)

Foto 3 da Cineastio (data di ultima consultazione 20/08/2021)