History of the city

The favourable position in which the city of Buthrotum was born and developed, in the ancient region of Chaonia, can explain the long occupation of the site (almost 200 ha): historical and archaeological evidence has highlighted indeed the frequentation of Butrint from the Bronze Age until the late 16th century.

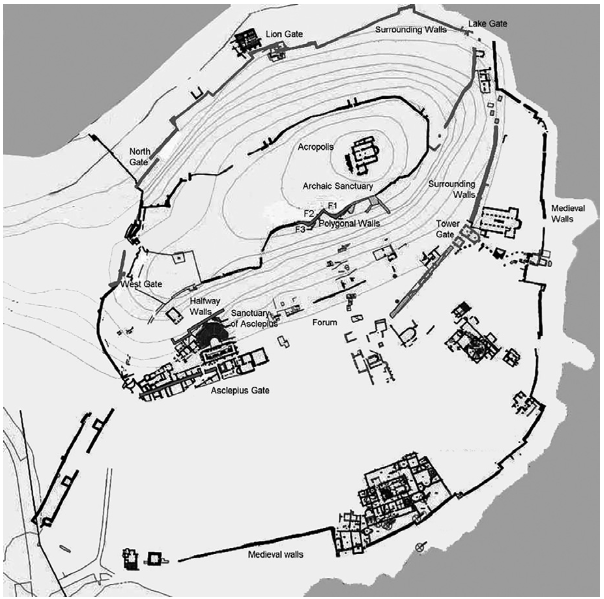

The first occupation of the site is dated to the mid/late Bronze Age on the central and western plateau of the Acropolis: it consisted of a small settlement, strictly linked to the Epirote substrate. From the 8th to 6th centuries BC the Acropolis was still inhabited, however the Corinthian pottery found on the site underlines the strict connection with Corfu, founded by Corinth in 733 BC, that now seems to extend its influence over the mainland. It is likely that this first community developed around a modest sanctuary built on the Acropolis itself, however, apart from pottery, one ash altar and few roof tiles, there are not other certain finds taht can be linked to the temple. Generally speaking, few evidences can be dated back to the Archaic phase of Butrint. The most relevant and imposing is the Archaic terrace wall on the south side of the hill, along with the Lion Gate relief, which depicts a lion biting a bull's neck and which has become one the most famous landmarks of the city.

From the 6th to 4th centuries BC there is the first proper urban phase, with the expansion of the settlement and the construction of the mid-slope circuit wall with four gateways. This is the same period of time that witness the construction of the Sanctuary of Asclepius, which will be the main centre of the city in the Hellenistic and Roman times, and the stoa for his pilgrims. The independence from the Corfiots gave Butrint the opportunity to become the administrative centre of the Chaonian tribe. This led in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC to one of the most prolific moments of the city, thanks to the expansion of the lower settlement, along with the extension of the wall circuit in the form of the temenos wall and the construction of many of the monuments that still attract the scholars' attention and wonder today: the Asclepieion Gate, the Tower Gate, the Theatre, the prytaneion, the Sacred Way, the Agora and its stoa, and the upper temple dedicated to Asclepius.

The Roman conquest, right after the battle of Actium, represents for Butrint another important moment of growth, at least until the 3rd century AD. Its connection with the Roman heritage had always been significant, since the site was believed to have been founded by Trojan refugees and that Aeneas himself had visited Butrint during his journey to Rome. The city was officially deducted as Roman colony twice: under Caesar in 44 BC (Colonia Iulia Buthrotum) and then under Augustus, named Augusta Buthrotum. The increasing richness of the city allowed the construction of new public buildings: the Forum and its surroundings, the Baths, the monumentalization of the Sanctuary of Asclepius, and the expansion beyond the early wall circuit to the south edge of the Vivari Channel. A new civic centre was placed on the Vrina Plain, connected by a bridge and the water main to the old town. The centuriation of the plain can be easily traced back to this enlargement and the growing number of villas, provided with access to the lake, between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD gives a clear idea of the importance that sea traffic and fishing must have had for the rich landowner of the area. The most evident signs of the economic and demographic growth of the city lies in the big number of monumental tombs located along the Vivari Channel.

After a major earthquake in the 4th century, Butrint thrived again thank to its connection to both side of the Mediterranean Sea, in fact many houses were built on both side of the Vivari Channel. Late Antiquity and Middle Age brought Christianity to the city: the ecclesiastical administration is proved not only by ceramics and coins but also by many significant buildings. The Acropolis Basilica was built in the 4th century AD, followed by the Great Basilica, the Baptistery and the Triconch Palace in the 6th century. In the Medieval times these were joined by the Lake Gate church and the Baptistery church (9h century AD). However, after a moment of decline in the 7th century, the city was reoccupied since it had become an important military base for the Byzantine fleet. It developed then other kind of necessities, in particular related to its defence: a brand new wall circuit is built between the 10th and 11th centuries AD along the shore of the Vivari Channel, while in the 12th century was built the Acropolis wall-circuit. Land control brought to the construction of the Acropolis castle on the lower plateau of the hill and to the first phase of the Triangular Fortress. These would have been reinforced during the last phase of life of the city in the 13th and 14th centuries under the Venetian Republic who ruled over Corfu and Butrint. It seems that the city was abandoned between 1517 and 1571, after the battle of Lepanto, and all the efforts were put in defending the fishing industry (fortified structures and fish traps) centred on the Vivari Channel. In the 18th century the city was conquered by the Ottomans, who used it as base to attack the isle of Corfu and continued exploiting the territory until the collapse of their Empire.

City map from Giorgi, Lepore, Comparing Phoinike and Butrint. Some remarks on the walls of two cities in Northern Epirus in Caliò, Gerogiannis, Kopsacheili, "Fortificazioni e società nel Mediterraneo occidentale. Albania e Grecia settentrionale. Atti del Convegno di Archeologia, organizzato dall’Università di Catania, dal Politecnico di Bari e dalla University of Manchester Catania-Siracusa 14-16 febbraio 2019", Edizioni Quasar, 2020, pp.153-181

Bibliography

- Hodges R. Excavating away the ‘poison’: the topographic history of Butrint, ancient Buthrotum in Hansen, Hodges, Leppard, "Butrint 4: The archaeology and histories of an Ionian town" Oxbow Books, 2013, pp. 1-21.

- Martin S., The topography of Butrint in Hodges, Bowden, Lako, "Byzantine Butrint : excavations and surveys 1994-99", Oxbow Books, 2004, pp. 76-103