A look behind the look. A reflection of male desires in hard-boiled stories

Cristina Apuzzo

Vulnerability, masculinity and femme fatale: a gender perspective approach to hard-boiled stories through some characters of most famous detective stories of the 1900s.

A reflection of male desires in hard-boiled stories

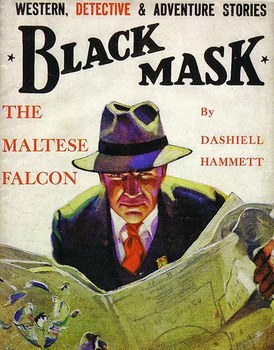

At the peak of its development in the 1930s, the hard-boiled genre had come to be a noticeably gendered one, in relation to both the characters and the ideology that permeated most of the stories. In their golden years, pulp magazines like Black Mask, which soon became specialized in hard-boiled stories, made this quite clear. Not only did they contain stories written almost entirely by men, but they were also addressed primarily to a male audience.

This is not to say that men alone wrote hard-boiled stories, but female writers were significantly less featured on magazines and, in general, not as widely acknowledged. As a result, hard-boiled novels tend to reflect the typical idea of masculinity and tough-guy image that was predominant in America during the 1920s and the 1930s. Of course, it would be wrong to assume that these views were universally shared and, indeed, they are often unrealistically extreme in the novels.

Still, readers admired the figure of the detective, sharing at least on a theoretical level his ideals, not least because they were already present in the American tradition from long before the genre was born. If anything, stories like The Maltese Falcon only intercepted a set of values that had been around for centuries, reinvigorating it for the readers’ benefit. The very editor of the Black Mask magazine, Joseph Thompson Shaw, had a clear idea of the ideal target of the magazine, writing in an editorial that the average reader

is vigorous-minded; hard, in a square man's hardness; hating unfairness, trickery, injustice, cowardly underhandedness; standing for a square deal and a fair show in little or big things, and willing to fight for them; not squeamish or prudish, but clean, admiring the good in man and woman; not sentimental in a gushing sort of way, but valuing true emotion; not hysterical, but responsive to the thrill of danger, the stirring exhilaration of clean, swift, hard action – and always pulling for the right guy to come out on top. (http://www.detnovel.com/blackmask.html originally from Joseph Shaw, quoted in Frank MacShane, The Life of Raymond Chandler (New York: Random House, 1976), 46)

A description that perfectly encapsulates the image of the tough-guy hero, which indeed had been part of America’s tradition since the myth of the frontiersman. As underlined by Sean McCan in the essay The hard-boiled novel, “hard-boiled fiction invoked the closely related tradition of the western, importing the conventions of frontier adventure to the territory of the industrial metropolis.” (McCan, p. 44)

What links the detective to similar characters in America’s literary tradition is also his inability, or unwillingness, to form long-lasting intimate relationships. In the words of George Grella, “his condemnation or rejection of other human beings unites him with the alienated and the lost of American fiction – Ahab, Huck Finn, Nick Adams, Joe Christmas, Holden Caulfield.” (Grella, p. 111)

Companionship is especially dangerous for a detective, because it can potentially cloud his judgement and leave him vulnerable. In this sense, loneliness seems to be the price the detective must pay to successfully do his job. Magazines like Black Mask also fulfilled a need for an all-male space that had become more and more rare.

Eric Smith underlines that “between 1880 and 1920 there was a transition in working-class life from the homosocial cultures of the Victorian era to the heterosocial cultures of the modern world”. (Smith, p. 31) What this means is that the presence of women in the workplace had been steadily increasing, which reshaped a space and an ideology that had previously been all-male. That is why, Smith adds, hard-boiled writing offered such a comfort to male writers, who could finally return to a space that was entirely theirs.

Hard-boiled writing culture functioned as a homosocial imagined community that addressed some of the needs once met on the shop floor, in the voting booth, or in the saloon. The male writers of the pulps saw themselves not as artists but as workmen who produced piecework prose for people like themselves. (ibid.)

Ads, too, contributed to the creation of a precise idea of masculinity based, in true hard-boiled fashion, on physical strength, courage and sometimes violent behavior. What they also advertised were typically male tools and attributes, thus promoting, “a variety of goods that could enhance one’s manliness: guns, motorcycles, bodybuilding programs, weight training” (ivi, 61). Almost inevitably then, in virtually all hard-boiled stories, women are often depicted as dangerous in some way, a threat that the detective must ultimately get rid of.

Getting involved with them, especially in a romantic way, is a risky business that can have potentially disastrous consequences. That is why, when women do appear in the picture, they turn out to be much more than simply characters in a story. They say something about the perceived ideas of masculinity and vulnerability, inevitably delicate themes when associated with a figure whose image is deeply rooted in toughness.

The threat of vulnerability in The Maltese Falcon

This is particularly clear in The Maltese Falcon, probably Hammett’s best novel. Sam Spade is the perfect prototype of the hard-boiled detective: clever, a no-nonsense attitude and, most of all, deeply devoted to his job. All through the novel, the emphasis is often on Sam’s toughness, at times exasperatedly so. The detective seems to be defined by it: it shapes everything he says or does. Indeed, at the very beginning of the novel it seems to transpire even from his physicality, all sharp angles and square forms. Hammett writes:

Samuel Spade’s jaw was long and bony, his chin a jutting v under the more flexible v of his mouth. His nostrils curved back to make another, smaller, (v. Hammett, D., The Maltese Falcon, New York, Vintage, 1972, p.3)

When Sam is hired by Brigid O’Shaughnessy, he is immediately wary of her. She is initially depicted as the typical damsel in distress, helpless in the face of danger and in need of protection from the detective. However, it turns out to be an act, as Sam himself realizes early in the story. Brigid was only feigning helplessness, while in the meantime working on her own schemes, trying to outsmart the detective, often by playing the card of her sensuality. This, too, is a stereotypical representation of the female figure in the hard-boiled genre, the femme fatal.

On a surface level, Brigid seems to be employed as a mere plot device to advance the story and ultimately mark the victory of the detective, who does actually manage to solve the mystery of the Maltese Falcon. However, not only is Brigid much more than that, but even Sam’s victory, all things considered, is rather ambiguous. In fact, while he does spot all of Brigid’s lies, finally uncovering the truth, it also comes at a cost. In this sense, the final passages of the novel are truly revealing. After discovering that Brigid was responsible for the death of his business partner, Sam is forced to hand her over to the police, despite having probably fallen in love with her. To a distraught Brigid, he explains:

When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t’ make any difference what you thought of him. [..] When one of your organization gets killed it’s bad business to let the killer get away with it. It’s bad all around – bad for that one organization, bad for every detective everywhere. (ivi, p.226)

Sam is in the detective business and must obey the rules, living up to the unspoken code and expectations that people have of him. In this sense, he appears to be defenseless against a system that cannot be contaminated by emotions, no matter how deep they are. Although justice is served in the end, it would not be entirely correct to say that the detective has succeeded. Indeed, as Jaba underlines in her essay, Sirens in Command; the criminal femme fatale in American hardboiled crime fiction,

the detective, as a representative of the law, appears to be tough but is in fact vulnerable, while the woman who appears to be weak and controlled at the end is the one who reveals the detective’s vulnerability and by so doing destabilizes the authority of law and order.

However, Sam is not only concerned with the possible damages done to his business, but also to himself as an individual. There is no separation between Sam Spade the man and Sam Spade the detective, as he has to keep up the façade of the tough-guy in all circumstances. Indeed, the ability to remain detached and unruffled by events, however unrealistic, has always been part of the fascination with hard-boiled figures such as Sam Spade. Much of Sam’s heroic image is based precisely on his almost super-human capacity to always control his impulses, which, as has been seen, comes at a great cost.

Both Brigid and the irrational feelings that Sam has for her are alarmingly intense and the detective cannot afford to give in to such emotions, not only to protect his business, but also and more importantly, to protect his identity and integrity as a man. That is why, after having carefully listed to Brigid seven logical reasons for which they cannot be together, Sam finally says: “If that doesn’t mean anything to you forget it and we’ll make it this: I won’t because all of me wants to – wants to say hell with the consequences and do it" (Hammett, p. 227)

The possibility of losing control is unthinkable, for both Sam the detective and Sam the man. Hammett’s prose is always matter-of-fact, perfectly reflecting Sam’s self-control. Still, emotions do transpire and it is again to Sam’s physicality that the reader should be paying attention. While rejecting Brigid and every possibility of romance with her, the detective’s face is “set hard and deeply lined”, and “his eyes burned madly”. The picture is rather grotesque: it is as though Sam’s face is distorting while trying to contain his emotions, all the while grimacing and gritting his teeth.

Iva Archer: the safe choice

The novel ends with Sam accepting to see Iva Archer, the widow of his business partner with whom he had been having a secret relationship. It is clear from the very beginning that the detective has no real feelings towards Iva, although he might have in the past. To Effie, Sam’s secretary who disapproves of how the detective previously used to play with Iva and now repeatedly rejects her, he admits to “never know what do to or say to women except that way” (ivi, p.28). The relationship with Iva is casual and unchallenging, which is why it is telling that Sam ultimately decides to pursue it. It is a safe choice, one that allows him both to have companionship and to preserve his tough persona.

Monster-like women in Chandler's narrative

In Chandler’s The Big Sleep, women are even more dangerous, even more femme fatale. What is particularly striking about Chandler’s female characters, though, is that that they are often depicted as somewhat monstrous creatures. Indeed, “Chandler’s femme fatales are not merely greedy and selfish, but often bizarre pathological creatures.” (McCann, p.53) The very first time Marlowe meets Carmen, the daughter of his client, he notices her “sharp predatory teeth”, “too taut lips”, a pale face that “didn’t look too healthy”.

Throughout the novel, she is increasingly described as a less-than-human creature and only in part is this motivated by the fact that Carmen turns out to be the murderer. It is a characteristic that seems to be associated with women in general. Entering a bookstore, Marlowe finds a woman and notices her smile, only to add that “it wasn’t a smile at all. It was a grimace”. Gradually, she begins a sort of transformation and a few sentences later Marlowe notes that “her eyes narrowed until they were a faint greenish glitter” and that her “fingers clawed at her palm”. Chandler’s detective has evolved from the unrealistic detachment of Sam Spade, adding an element of sentimentality to his persona. Indeed, as McCann rightly underlines,

Caring [..] was the key ingredient that Chandler brought to the detective story. Where Hammett’s detectives were cool professionals, Chandler’s heroes are men who feel things intensely (ivi, 52)

However, this different attitude is not always evident in the novel. It is again in the The Big Sleep that Vivian Sternwood, trying to extort some information from the detective by flirting with him, finally has to desist, saying to Marlowe that “[he’s] the hardest guy to get anything out of. You don’t even move your ears” (Chandler, p.52). A few moments later she reiterates the concept, adding that Marlowe is “as cold-blooded a beast as [she has] ever met”. Intimacy is something that Marlowe both seeks and tries to escape. After kissing Vivian briefly, the detective instantly regains his professional composure, claiming that, although he’s not an “icicle”, he has been hired by Vivian’s father and must complete his job.

Marlowe's vulnerability

Still, it gradually emerges that the cynic attitude he displays is merely a façade and that, below the surface, he is painfully human. Indeed, at times he seems to despise the tough-guy attitude, ridiculing it when he perceives it in others. Entering the apartment of Joe Brody, he is immediately threatened with a gun and, when Brody tries to further scare him with words, Marlowe comments that “his voice was the elaborately casual voice of the tough guy in pictures. Pictures have made them all like that”. Toughness is not a standard Marlowe can live up to because, particularly in his behavior towards women, he is profoundly insecure.

It transpires when, coming home after an already upsetting encounter with Vivian, he finds Carmen naked in his bedroom. It is, quite literally, an invasion of his personal space, almost a contamination. Not by chance, this is the point of the novel in which Carmen most closely resembles a wild beast. In Marlowe’s agitated eyes, her face looks “like scraped bone”, her eyes are blank, her lips move almost on their own accord, “as is they were artificial lips and had to be manipulated with springs” and she seems to emit hissing noises “sharp and animal”. Marlowe feels violated in the most private space he owns:

This was the room I had to live in. It was all I had in the way of a home. It was everything that was mine, that had any association for me, any past, anything that took the place of a family.

After Carmen leaves, Marlowe finally loses his temper and tears “the bed to pieces savagely”. It has been rightly argued that “Marlowe’s vulnerability – and his realization of it – is the main motive behind the tearing of the sheets, rather than “woman-hating” as such.”(Jaber, p. 15)

The fear of feeling exposed in In a Lonely Place

This vulnerability is also what terrifies the protagonist of In a Lonely Place, by Dorothy B. Hughes. Dix is a war veteran trying to settle back into civilian life, but clearly having a hard time doing so, as anxieties and a difficult past have turned him into a serial killer that murders innocent women. What seems to trigger Dix’s rage is the female gaze. In the novel, he feels dangerously exposed whenever Sylvia or Laurel, the two main female characters, lay their eyes on him.

From the beginning, they are depicted as smart, observant and strong women, much more so than the detective of the story, Dix’s friend, Brub. Sylvia is right when she tells Dix that “[Brub] just looks at the envelope. Now I’m a psychologist. I find out what’s inside”. He is wary of her precisely for this reason, as “something was there behind the curtain of her eyes, something in the way she looked ad Dix, a look behind the look”. Laurel, too, can see through Dix’s façade and quickly decides to avoid him, which only succeeds in further irritating him. Reading about Dix’s past, we also learn about his dissatisfaction with standard models of identity, especially male identity, with which he necessarily had to confront himself. In Dix’s words,

A fellow had to have money, you couldn’t get a girl without money in your pockets. A girl didn’t notice your looks or your sharp personality, not unless you could take her to the movies or the Saturday night dance.

It is unsurprising, then, that he chooses to surround himself with rich boys while attending University, taking advantage of their financial resources while, in turn, providing them with humorous stories. It was a humiliating experience for Dix, who admits that “as long as you toadied, you had a pretty good life”. WWII came as a blessing for him and for many other men like him, as he could finally find true and genuine validation regardless of his wealth. In fact, during the War, “you were the Mister, you were what you’d always wanted to be, class.” Significantly, in the novel, Dix has taken over the house, the car and, on the whole, the lifestyle of Mel Terriss, one of his rich colleagues from University.

Listening to one of Brub’s friend say that the only reason a man would turn out to be a murderer is insanity, Dix reflects that “it would never occur to him that any reason other than insanity could make a man a killer”. Indeed, the frightening doubt raised by the book is that society as it is, with its absurd standards encaging men and women alike, could be creating criminals. Unconceivable standards of masculinity have contributed to making Dix extremely insecure and wary of women. The point, as Megan Abbott underlines, is precisely that

In another noir novel, Laurel and Sylvia might be presented as femme fatales, seeking to entice and entrap Dix. But in Hughes’s hands, they are neither vixens nor passive victims. They are dual investigators, and at least as powerful as Dix fears. They see through him, see him for what he is. The more penetrating their gaze, the more hysterical he becomes. And to Dix, nothing could be more threatening, or more emasculating.

In more general terms, the same thing can be said of virtually every male character in the hard-boiled genre. In different ways, Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe were just as suspicious of women and for very similar reasons. On a surface level, then, it is true that hard-boiled stories are about a male-centered universe, which is reflected in the language, the characterization of the detectives and their interactions with people around them. However, women do have a fundamental importance, even when their role is apparently secondary. Indeed, whatever their actual degree of agency in the story, their power is precisely in their ability to see the detective “for what he is”, uncovering the cracks in his apparently tough persona and challenging the traditionally accepted standards of masculinity.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Chandler R., The Big Sleep, Farewell My Lovely, The High Window, Everyman’s Library, 2002.

Hammett, D., The Maltese Falcon, New York, Vintage, 1972.

Hughes, D.B., In a Lonely Place, Penguin UK, 2010, Kindle Edition.

Secondary Sources

Abbott M., The Gimlet Eye of Dorothy B. Hughes, http://womencrime.loa.org/?page_id=89 (17.06.2017)

Grella G., The Hard-Boiled Detective Novel, in Robin W. Winks, (a cura di), Detective Fiction: a Collection of Critical Essays, Woodstock, Vermont, Country Man Press, 1988.

Jaber, Maysaa Husam, Sirens in Command; the criminal femme fatale in American hardboiled crime fiction, University of Manchester, 2011. (available to the link https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/sirens-in-command-the-criminal-femme-fatale-in-american-hardboiled-crime-fiction(a6a35b81-665e-4f1a-9f3c-a8c286fe3796).html 14.06.2017)

McCann S., The hard-boiled novel, in Catherine Ross Nickerson, (a cura di), American Crime Fiction, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Smith Erin, Hard-Boiled, Temple University Press, 2010 «A look behind the look»: Female gaze and vulnerability in hard-boiled stories

Immagini

Foto 1 da luigibicco.blogspot.com (data di ultima consultazione: 01.09.21)

Foto 2 da wikipedia.org (data di ultima consultazione: 01.09.21)

Foto 3 da bookmarks.reviews (data di ultima consultazione: 01.09.21)