Villaggio del Pescatore Lagerstätte

The Villaggio del Pescatore quarry near Trieste stands as the most informative locality within the palaeo-Mediterranean region and represents the first, multi-individual Konservat-Lagerstätte type dinosaur-bearing locality in Italy.

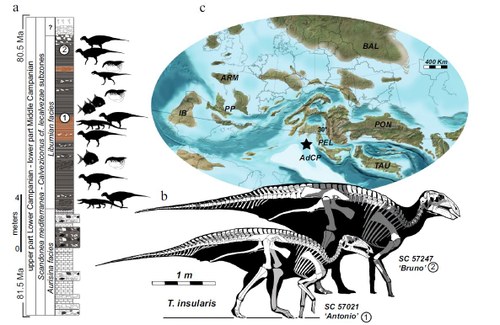

Chiarenza et al., 2021 Scientific Reports 11:23295

This project aims at addressing geological, paleontological and paleobiogeographic unsolved aspects related to the most important Campanian fossil locality of Europe: the Villaggio del Pescatore site (Duino-Aurisina, Trieste, Italy). Although this locality has achieved notoriety for the exquisite preservation of its dinosaur-dominated fossil assemblage, the site and adjacent exposures play a core role in our understanding of the Adriatic, Late Cretaceous carbonate platforms as well as in determining environmental and biogeographic patterns in the European archipelago. The site is located on private land, it is currently under the legal protection of the Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio del Friuli Venezia Giulia, and officially included into the Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) Italian geosite inventory.

To properly address all crucial and unsolved scientific aspects of the area and to set the ground for compelling activities connecting science with the socio-economic fabric, this project has four connected objectives:

- to provide the first geological, numerical and analogic modeling of the structural and sedimentary processes of the site, which represent a depositional ‘unicum’ in the current literature;

- to assess the complex taphonomic history of preserved biota and discuss its paleoecology and paleobiogeography following the recent reevaluation of the site's age, also by applying new cutting-edge methodologies including nano-ct scannig of fossil elements;

- to consolidate paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental data focusing on regional tectonostratigraphic setting and genetic story of vertebrate-rich paleoexposures;

- to flank ongoing activities intended to promote education, exhibits and national-international projects for the safeguard and enhancement of the site.

This project is grounded in a long-lasting collaboration between scientific partners and with all necessary authorizations from the Ministry. Active research activities involve the University of Bologna (Dept. BiGeA), University of Trieste (Dept. of Mathematics and Earth Sciences), the Civic Museum of Natural History, ISPRA, Elettra Sincrotrone, and ZOIC s.r.l.

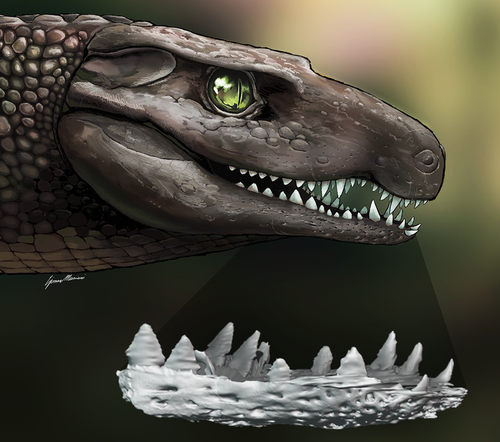

Overimposed Acynodon skull photo and transparent render with highlighted teeth

Acynodon adriaticus - an overlooked creature

Although Villaggio del Pescatore became famous thanks to the hadrosauroid dinosaur Tethyshadros, a second vertebrate in excellent condition was discovered during the 1998-99 quarrying campaign. It was a small, robust crocodylomorph, represented by two articulated individuals and some isolated material. The better preserved of the two specimens was described in 2008 and established as the holotype of a new species in the genus Acynodon, A. adriaticus. At the time, the genus Acynodon was known from Spain, France, and the famous Hateg Basin in Romania (both from fairly complete skulls and from much more fragmentary remains and isolated teeth), and phylogenetic analyses placed it among the globidontan alligatoroids — therefore, an archaic representative of the alligator family. Today, the consensus is that Acynodon belongs to the extinct family of Hylaeochampsidae, a much more archaic clade widespread throughout Europe during the Cretaceous period. Many members of Hylaeochampsidae exhibit peculiar morphologies and bizarre feeding specializations, with a particular tendency to lose the conical, canine-like teeth typical of predatory crocodiles (the name "Acynodon" itself literally means "without canines") and develop very large posterior teeth.

With two articulated specimens, Acynodon adriaticus is one of the best-preserved hylaeochampsids. Between 2022 and 2024 both specimens were re-examined by our research team, which, thanks to new analyses and a strong multidisciplinary approach, revealed previously unknown details. A redescription of the more gracile specimen has improved phylogenetic resolution regarding its placement within Hylaeochampsidae, which still remains quite problematic pending a comprehensive redescription and revision of all its members. Furthermore, although the size of this individual is almost comparable to the robust holotype, a conflict is evident between some skeletal features—indicators of immaturity—and histological analyses, which instead suggest an age perhaps over 30 years.

The type specimen, despite its perfectly preserved skull, continues to hide important anatomical details from direct observation due to the large amount of matrix still surrounding it. In 2024 we published the results of an in-depth microtomographic analysis on the skull performed at ELETTRA, a highly advanced research facility near Trieste. Despite numerous challenges related to the high density of the limestone matrix, the team managed to digitally prepare the skull and expose key anatomical features such as sutures, foramina, internal morphologies and teeth, allowing the specimen to be described with renewed clarity. This opportunity also led to the consideration of some evidence of this animal's personal life history: in addition to a fractured right forelimb that had already healed at the time of death, it showed abnormal ossifications in the mandible—a symptom of severe craniomandibular arthritis—and a likely supernumerary tooth. Direct comparison with CT scans also confirmed that a mysterious fossil still in the Villaggio del Pescatore quarry, difficult to interpret by itself, represents another Acynodon skull—a third specimen still awaiting extraction!

A nutcracker crocodile

The availability of such a large amount of information allows us to paint a fairly accurate portrait of the appearance and biology of A. adriaticus. At just over a meter long, this crocodilian was smaller than even the smallest dwarf caimans living today. Its massive skeletal structure accentuated its stocky proportions, crowned by an extremely short and broad, vaguely triangular skull. Its small orbits suggest reduced eye function, a common response among vertebrates living in murky waters with poor visibility filled with algae and aquatic vegetation. A. adriaticus was likely a slow-growing, lethargic animal, almost always hidden on the bottom of organic-saturated waters, constantly probing the substrate with its robust but sensitive snout in search of bivalves, gastropods, and large crustaceans. Its specialized dentition was designed for crushing: the front of the jaw housed small, protruding, chisel-like teeth, whose frequent wear suggests they were used to grasp hard, abrasive objects. The back teeth, huge and globular in shape, were covered with incredibly thick enamel with a magnificent beaded texture: perfect tools for gripping shells and exoskeletons and crushing them with relentless efficiency. Crushing the tough calcareous shells likely resulted in rapid tooth wear: tomographic data show that while the anterior teeth did not undergo frequent replacement, the posterior molariforms were always ready to be replaced by a battery of enormous replacement teeth stacked inside the sockets. This pattern is opposite to modern crocodiles but is shared with other ancient durophagous specialists such as the Triassic placodonts. The age of Villaggio del Pescatore corresponds to a phase of extreme diversification of gastropods and other freshwater and brackish water mollusks, facilitated by an explosion of favourable marshy habitats and the abundance of resources following the widespread diffusion of angiosperms. Part of a clade already capable of exploiting unusual resources, the lineage which led to Acynodon adriaticus responded to those environmental conditions by adapting to consume animals ignored by other species, securing a place in the thriving ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous and producing the most durophagous crocodilian ever discovered.

References

Muscioni M., Chiarenza A. A., Fernandez D. B. H., Dreossi D., Bacchia F., & Fanti F., 2024. Cranial anatomy of Acynodon adriaticus and extreme durophagous adaptations in Eusuchia (Reptilia: Crocodylomorpha). The Anatomical Record, 1–32.

Muscioni M., Chiarenza A., Delfino M., Fabbri M., Milocco K., Fanti F., 2023. Acynodon adriaticus from Villaggio del Pescatore (Campanian of Italy): anatomical and chronostratigraphic integration improves phylogenetic resolution in Hylaeochampsidae (Eusuchia). Cretaceous Research, 151, 1–21.

Delfino M., Martin J. E. & Buffetaut E., 2008. A new species of Acynodon (Crocodylia) from the upper cretaceous (Santonian–Campanian) of Villaggio del Pescatore, Italy. Palaeontology, 51: 1091-1106.

Delfino M., Martin J. E. & Buffetaut E., 2008. I coccodrilli del Villaggio del Pescatore: una panoramica generale. Atti del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Trieste, 53: 277-284.

A life rendition of Doratodon, with a highlight on available material from Villaggio del Pescatore. Artwork by Simone Muscioni.

Doratodon – an unexpected new presence

As a relevant part of the Villaggio del Pescatore research project, the revision of the large fossil collection housed in Trieste led to the reconsideration of many overlooked specimens. While working on other fossils, a diminutive, isolated jaw fragment captured the attention of the research team. Previously dismissed as undiagnostic material, it certainly belonged to a crocodylomorph of some kind. By closely checking the little jaw under a microscope, two tiny teeth became evident, and the larger one – unfortunately broken near its base – was bearing fine serrations on its cutting edge. A crocodilian with serrated teeth pointed to an exciting occurrence: during the last 200 million years many crocodylomorphs developed theropod-like ziphodont teeth, but very few of them are known from the Cretaceous of Europe.

To better understand the identity of the small fragile jaw – still half embedded in a limestone slab – the team CT scanned it at ELETTRA’s Tomolab and managed to virtually restore the jaw bones, an almost complete set of teeth and even the inner neurovascular vacuities. The conclusions were compelling: the jaw fragment from Villaggio del Pescatore represents the first definitive occurrence of the terrestrial crocodylomorph Doratodon from Italy. Two species of this small predator are currently known from other European localities: the large D. ibericus from Spain and the smaller, better-known D. carcharidens from Austria, Hungary and Romania. Not surprisingly, the specimen from Villaggio del Pescatore perfectly aligns with the morphology of the eastern taxon, filling a biogeographical void and further highlighting the importance of the Adriatic carbonate platforms for faunal dispersals during the Late Cretaceous. With this research opportunity there also was the occasion to inspect enigmatic teeth coming from the Slovenian fossil locality of Kozina, two steps away from Villaggio del Pescatore; Slovenian collegues had already noticed suspicious similarities with teeth of Acynodon adriaticus, and the occurrence of Doratodon too was confirmed. As further research is being performed by the Slovenian institutions, these might be the first steps to reveal that Villaggio del Pescatore and Kozina might preserve the same faunal assemblage!

A land crocodylomorph

Doratodon was traditionally considered member of Notosuchia, the great lineage of terrestrial crocs that birthed the monstrous baurusuchians and sebecids, but its evolutionary identity remains nowadays somewhat controversial. New, more complete material from Hungary might suggest that this creature was instead an unusual member of Paralligatoridae, which convergently evolved terrestrial adaptations. Regardless of its identity, the altirostral skull and ziphodont, blade-like teeth converge to the same interpretation: unlike other semiaquatic crocodilians, this 1.5 meter long carnivore stalked its preys on dry land. The heavily branched trigeminal architecture observed in our specimen might testify the retention of a very sensitive snout, akin to semiaquatic species; whether this represents a retained ancestral feature or a foraging adaptation remains to be understood. The relatively small size and unspecialized teeth replacement pattern suggest that Doratodon filled the niche of a versatile mesopredator. Roughly comparable to a crocodilian version of a large monitor lizard, this vicious generalist lurked the undergrowth of Villaggio del Pescatore haunting small animals and young dinosaurs.

Reference

Muscioni M., Chiarenza A. A., Nicholl C. S. C., Perentin T., Dreossi D. & Fanti F., 2025. A ziphodont crocodylomorph from Villaggio del Pescatore Lagerstätte (Campanian, Italy). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 205: 4.

The fauna of Villaggio del Pescatore

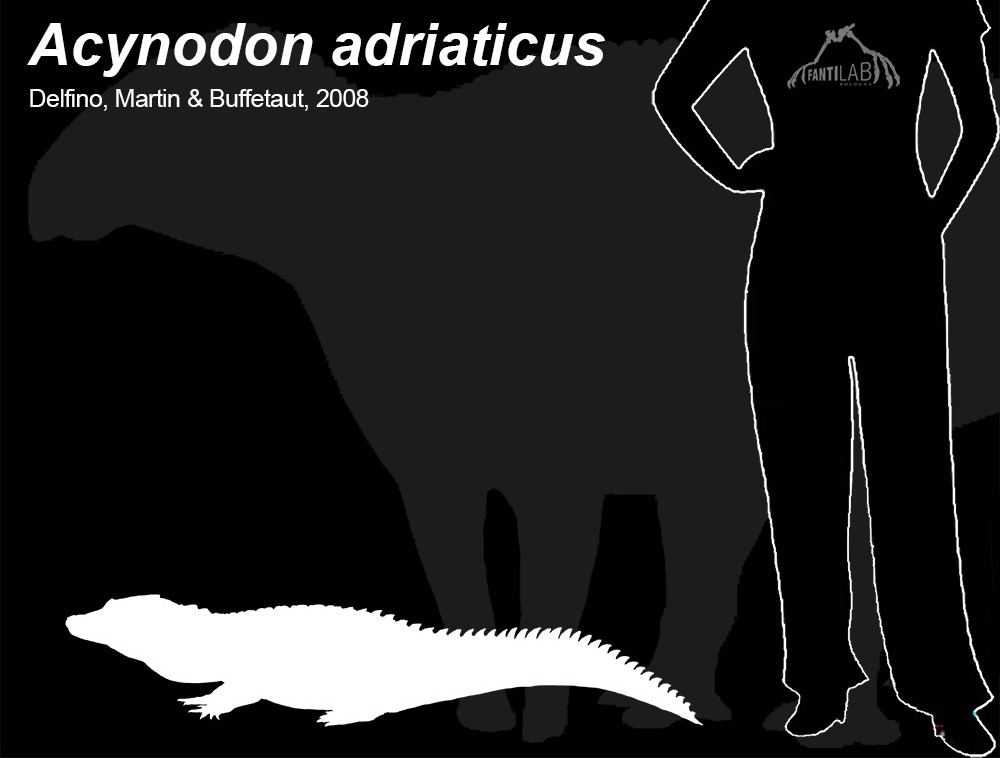

Size chart with Acynodon adriaticus (white), Tethyshadros (grey) and a 170 cm tall human.

Size chart with Doratodon cf. carcharidens (white), Tethyshadros (grey) and a 170 cm tall human.