Women in the Struggle: Female Activists and Writers in the Strife for Rights

Zoe Tsaousaki

The oncoming Jim Crow laws era that followed slavery has been recorded as an equally cruel period for the African-American populations of multiple southern states. Nonetheless, ill-treatment even in simple tasks presumably ignited the spark in black men and women to reconsider the conditions under which they, as Fannie Lou Hamer proposes, “existed” and manifested tremendous courage to bring about desired change.

The plurality of means by which women participated in the struggle (1954-1965), as well as their robust, well-organized stances against obstacles are evidential of their momentous support to the movement; traditional means such as rallies, where they often occupied cornerstone positions – and the sophisticated reacting force of literary production are indications of women’s empowerment within the movement.

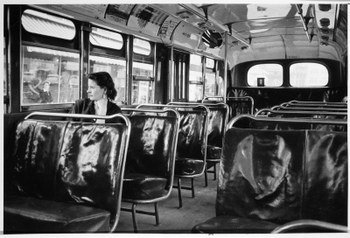

A number of female voices were raised to assist the fight and a pioneering part of activists both in organizing and leading were women. Among them were Rosa Parks, Dorothy Height and Fannie Lou Hammer, whose names were repeatedly highlighted throughout history. Parks’ resisting act of not ceding her place on the bus and its unimaginable impetus, Height’s ardent speeches and Hammer’s ongoing effort, have iconized their figures –along with many more women activists’ – who courageously sustained the movement.

1. Three female figures in the Civil Rights movements

2. The Montgomery bus boycott and the march on Washington

3. The Women's Conditions in the South

4. Female power and leadership

5. Black female writers: Shay Youngblood

6. Black female writers: Ntozake Shange

7. Black female writers: Gwendolyn Brooks

8. Conclusions

9. Works Cited

1. Three female figures in the Civil Rights movements

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks’ action begun in 1943 by joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as a secretary, in the area of Montgomery. Her vision for the movement to go forward was that young people should be in the battlefront (Houck, Dixon, 37). Indeed, her decision not to comply with the irrational demand of ceding the bus seat tackled the problem of transportation and emphasized the dimensions of the everyday difficulties black people were confronted with, encouraging a lot of people to provide support. The series of events that followed had a domino effect on white supremacy beliefs and the segregation policy.Parks herself stressed the absurdity and falseness of the Jim Crow ordinances, if seen by the imposers themselves “from a Christian and human standpoint” (Parks qtd. in Houck, Dixon, p. 40), simultaneously familiarizing audiences with the movements’ ethics and morality views.

Unlike Parks, Dorothy Irene Height, was active within the movement from quite an early stage, employing her rhetorical talent in the marshal of supporters. She served in multiple associations, among which were Young Women's Christian Association and the National Council of Negro Women that she was also president and chair of. She also won a plethora of medals for her action, including the Spingarn Medal and the 2004 Congressional Medal (Houck, Dixon, p. 220). Height’s strong presence backed many major events. In her speech delivered in Selma, Alabama, she recalls the massive march on Washington D.C. where “the United States of America had an object lesson, because they saw there the way at which people who stand for something can stand together” (Height qtd. in Houck, Dixon, 222). She drew parallels among the historic march and the resistance to the oppressive sheriff of the town of Selma, undertaking the encouragement of its people and proving exceptional oratorical skill, which she was recognized for.

Another legendary persona in the Civil Rights struggle is Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer, who was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and outspokenly embraced the grassroots leadership philosophy it advocated (Houck, Dixon, p. 280). According to this perspective, the movement would unravel from a small community organization, where local centers of action were crucial. In Hamer’s case, as in Parks’, shared personal experience became compelling and turned the spotlight to unseen parts of suffering as black females experienced it. Not only had she fallen victim of physical abuse, but following the illegitimate convention, the perpetuators of such gruesome deeds were vindicated (Hamer qtd. in Houck, Dixon, p. 281). Having accepted Malcolm X’s invitation, she delivered a powerful speech in Harlem, referring to the personal and the social interacting with one another within the larger, tragic context of segregation, exclusion and the violation of rights. Furthermore, by the means of micro and macro mobilization racial matters were to change for all, in the United States.

The din of the continuous events by which colored people pursued equality and integration, proved extremely important for sustaining the movement. Such relentless effort, as organized by the civil rights advocates and associations, drew public interest and demonstrated how urgent a shift in ideas was. Women, who were often leading the path or were simply present and supportive, sought justice for all the black generations that were mistreated. Some major points in the history of civil rights were the march on Washington and the Montgomery bus boycott.

2. The Montgomery bus boycott and the march on Washington

Mary Fair Burks gives an account of women’s first subtle steps towards reassuring better conditions for black people. She refers to a “three tier approach”, including the fight for political and suffrage rights, protests about the abuse of blacks on buses and education; In the light of Plessy, we were not fighting segregation as much as the abuses of Negroes, who constituted the buses’ major patrons” (Burks, p. 81).

Having examined the financial support their folk provided to the bus lines, as well as exploitation instead of proper service –they were repaid with - throughout 1954 and 1955, they met six times with the officials and spoke of a citywide boycott in case their demands were overseen (Robnett, p. 56). The boycott, however, seemed an unavoidable practice at that moment, and lasting for over a year, it steadily paralyzed the local transportation service, which lost a crucial part of its annual revenue due to colored people’s united denial to use the service after Parks’ arrest. The result is specifically described as “a newfound racial consciousness that far transcended the city limits of Montgomery” (Houck, Dixon, p. 38). Another important female figure in the initiative was Jo Ann Robinson, who assumed action and produced leaflets at the outbreak of the boycott.

Not being involved in formal leadership, these women took a step towards equal treatment and riveted the effort that humanized transportation for black populations. Another leading event within the Civil Rights movement was the march on Washington D.C, towards the symbolic Lincoln Memorial. The populous rally of 250.000 participants gave an object lesson to America, as Height states (Height qtd. in Houck, Dixon, p. 222). Despite all fear and hesitancy, unity shone through and was enough, according to Height, to achieve improvement.

“But whatever our differences, I am renewed in my feeling tonight that there is one thing in which we are all united; we want our freedom and we want it everywhere in our country, now” (Height qtd. in Houck, Dixon, p. 223), she concluded. The march on Washington represented consensus among several associations and the mutual passion for freedom, capable of driving people to defend their inextricable rights. Other unexpected supportive attitudes came to the front, such as Washington’s chief of the police, who did not hesitate to further empower and encourage the participants.

3. The Women's Conditions in the South

The feelings of hesitancy and withdrawal among women seem justified when one takes into account the several obstacles they had to confront. The cultivation of a violent, supremacist attitude that prevailed the South until the 1960s was apparent in the behavior towards women. Several humiliating incidents, given in first person narration, demonstrate the lack of respect they came across in everyday life. The re-occurring pattern that derives from their narrations was that they were often forced to stand in buses, arrested when they refused to do so, had to endure sexual assault and were sometimes fiercely beaten, as in Hamer’s case.

The speech in Selma contains quite an upsetting testimonial referring to the tragic moment of her unjustified arrest in Winona, Mississippi:

“I don’t know how long this happened until after awhile I saw Miss Ponder pass my cell. And her clothes had been ripped off from the shoulder down to the waist. Her hair was standing up on her head. Her mouth was swollen and bleeding” (Hamer qtd. in Houck and Dixon, p. 285).

As far as her own treatment is concerned, she states: “while they was beating, I was screaming. One of the white men got up and began to beat me in my head” (Hamer qtd. in Houck and Dixon, p. 285). No medical support was provided for these women by the country and the abuse resulted in permanent eye damage for Hamer. The deep southern conservative society did not share such low standards of behavior for all women, though. The well-educated southern belle of the antebellum seemed to be the extreme opposite of the black woman during the same era. The latter character was likely to perform manual exhausting tasks, have the role of a caregiver and be treated in a gruesome manner, whereas the first category was raised in an upper socioeconomic environment, assisted in housework by helping employees and generally admired by the community.

“If the image of the delicate alabaster lady were to retain some semblance of truth […] The image of the southern lady, based as it was on a patriarchal plantation myth, demanded another female image, that of the mammy” (9), claims Christian. Such predecessors left a heritage of domesticity and restriction, nonetheless, the upper-class white woman or housewife remained a subject of high status, who black men were often accused of desiring and white men vowed to protect.

4. Female power and leadership

At this point, the power of women in leadership can be discussed a little further. “[W]hen women as formal leaders were faced with the dominance of the formal male leaders … their ideas and desires were overridden or discouraged” (165) Robnett supports, also focusing on Hamer’s and Richardson’s high positions, naming them “uncommon and by default” (Robnett, 165).

The mild terms that do not describe conflict, present accumulated differences which hampered their endeavors. Within the broader context, the lack of respect towards women’s ideas had possibly penetrated the most democratic leaders’ action, though recompensing for it with an analogous form of power, bridge leadership and organization. The enchained obstacles were still many.

Two different models were leading the events, separating protesters and their white counterparts, while Richardson’s uncompromising stance in Cambridge was criticized by the supreme white authority and Black male leaders. Giddings comments that radicalism in terms of activism, paradoxically, did not coincide with more liberal attitudes and a barren, gender-tight area of leadership was attributed to men (313). Apparently, the fierceness of the violent model had ingrained female leadership and complicated matters in likewise turbulent times.

5. Black female writers: Shay Youngblood

Apart from taking on significant places in the organization and carrying out political action, African-American women also lead literary production, where they frequently used to chronicle the hardships of being black in segregated parts of the United States. Among other prolific black female writers were Shay Youngblood and Gwendolyn Brooks, whose themes were to a large extent affected by racial discourse and the way white supremacy theories dominated common people’s lives.

Their much hated and discriminated race had started to acknowledge its own power and take pride in its much debated identity, while a part of it participated in the Civil Rights movement. To begin with, Shay Youngblood, who experienced segregation only as a child, is quite concerned with the role of memory and ancestral power channeling itself in the role of an animating spirit. Blackness and femininity are interlocked in her characters, as in Black girl in Paris and “Spit in the Governor’s tea”. Such characters have distinct perception and worldview, since they experience reality as the other; people who are excluded and whose exclusion cannot be explained reasonably. In Black girl in Paris the themes of descent and identity are pervasive; the protagonist suffers several crises regarding her identity, which is reshaped and reconsidered in the light of new surroundings and experience:

““Who am I?” “Daddy’s African princess.” “How do you know for sure?”” “I discover that nothing is ever certain. … changed.” (Youngblood, 15).

In “Spit in the Governor’s Tea”, Miss Shine turns dangerous and unapologetic when injustice is aimed towards black children. “She kept thinking that they was all just children. Why couldn’t the governor see that?” (Youngblood, p. 56), the author comments. The idea proposed hereby, represents the black people’s trust in the next generation’s strength and the effective cooperation in the Civil Rights initiatives, as many activists declared in the same era.

In the short story by Youngblood, the black female is found in the inferior position of being dictated what to do, both by Mr. Polk and by the governor. “'What do you wanna work for?' He would scream, so everybody in the neighborhood could hear and know he was a man” (Youngblood, 52) shouts Mr. Polk, her husband, who neither appreciates nor tolerates Miss Shine’s contribution nor support. The governor, as a powerful white male figure can act even more dominantly, giving commands and employing the imperative: “'Shine, quick, fix the children some hot chocolate'” (Youngblood, 56).

At this point, Rousseau’s latter depiction of a black mother can be added. Despite the relentless cinematic efforts to reject any African-American woman role-model, she takes into account the different types of abuse these mothers went through, naming it “raced, classed and gendered” (Rousseau, 467). She further refers to the unequal conditioning within society and trivial distribution of financial aid, when reviewing their responsibilities. “Given the history of black women and labor in the United States, this is an ironic ultimatum, as Black women have historically been a primary source of labor, both in the wage and slave labor systems” (467), Rousseau supports.

6. Black female writers: Ntozake Shange

Likewise, the prolific Ntozake Shange ventured on writing a chore poem for colored girls who have considered suicide that reflects upon the suppressed moments the African American female youth have experienced.

The thematic scope of it, although focused on women, remains broad, while its main objective is to unveil several forms of customary oppression, as women face it. As Richard states, “[n]ot only does she deal with a woman's sexuality and body images, but she also deals with a Black woman's need to defy the outside world through nurturing and supporting herself” (21).

Shange herself has explained multiple times how she expressed the emotions of alienation and psychological violence via the chore poem. “It’s sort of like, it is self-explanatory but then again it can become whatever you want it to be, because it has to do with mulling over who we are and establishing that we have a right to live and we’re natural as rain and sun and the mountains and trees”, she proclaims. (Shange, 3). In this passage, there is evidence of collective consciousness, which had previously united the Civil Rights activists, and participants of the movement, in the arduous struggle to be primarily regarded as natural and consequently as equal. Furthermore, Shange devotes the play to the spirits of her grandma and great aunt, honoring her African-American ancestry.

Another observation that presents a close relationship with ancestry and the appreciation of black heritage is that Shange uses the word “colored” in the title; though not politically neutral and occasionally offensive, it is a word choice that acknowledges a past of discrimination and segregation. This violent past, as the activists themselves construe it, can be held responsible for current black female stereotypes and prompting the formation of certain conventions as to how they are to be treated by the opposite sex. In when the rainbow is enuf, the ladies dressed in the colors of the rainbow, narrate the personal behind the political. The lady in brown speaks of

“dark phases of womanhood of never havin been a girl” (Shange, 1).

and continues by imploring anyone to “sing a black girl’s song to bring her out to know herself … cairn/ struggle/ hard times” (Shange, 2). The prominence is placed on a demand to provide a liberating reality for the youth, in a context of acceptance and concord. There seems to be a kind of exceptional loyalty among the generations of the African-American, whose homophonous resistance tried to protect their descendants from their own traumatic reality.

7. Black female writers: Gwendolyn Brooks

White supremacy politics formed appalling attitudes towards women that were perceived as reasonable by the perpetuators at the time; namely, the social stratification of the American South was quite rigid and pervaded by racial standards, proved by women of letters narrating multiple personal indicative events during the Jim Crow rule. Such styles of behavior permeated black women’s quotidian experience in the years to follow, arousing questions about a white woman’s status during the same era; a ballad written by Gwendolyn Brooks explores the subject by analyzing a white female character’s psychology.

Gwendolyn Brooks, who was highly esteemed during the burdensome decades of the Civil Rights struggle, remains a figure of paramount importance in American literature. The commitments to defend black people’s identity, the political character of her works as well as their literary value, render Brooks a rather memorable persona. Brooks’ themes vary and discuss the lives of black female characters, the urban surroundings black people are mostly found in or provide political arguments against segregation and raw violence. Among her most notable works are In the Mecca, A Street in Bronzeville, and Annie Allen. Initially, the problematic of identity seems to preoccupy the poet from an early stage in her career. Specifically, in the 1956 collection, Bronzeville Boys and Girls, she writes:

“Do you ever look in the looking-glass And see a stranger there? A child you know and do not know, Wearing what you wear?” (Brooks, 22).

Although there is no apparent correlation between blackness and identity in the poem, she has devoted the collection to her own children and the title itself refers to a northern black metropolis and a locus of political action during the 1950s. The institution of slavery, the humiliating conditioning of black people and the segregation politics, as well as the debate of religion during the Civil Rights movement, when oftentimes Muslim renaming took place, posed fundamental questions regarding their identity. Brooks, motivated by the urge to condemn the unjust murder of Emmett Till, gives her own insight on the matter. A Bronzeville Mother Loiters, Meanwhile a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon is narrated from the point of view of Carolyn Bryant, a white, middle-class wife. Except for being confronted by the torturing recurring image of the black youth’s blood, the woman undergoes taunting crises correlated with her position in the Southern American society of the 1950s. Despite the progress early feminists achieved in protecting the white woman’s rights, the centrality of the woman’s reproductive and motherly role, as well as the definition of an acceptable feminine appearance remained quite intact, as Brooks describes.

“The beautiful wife. For sometimes she fancied he looked at her as though Measuring her. As if he considered, had she been worth it?” (77).

Bryant is concerned with her image, as if it could justify the gruesome act and her beauty could out-scale, in her husband’s mind, the nefariousness of his deed; not only are the woman’s exterior characteristics emphasized over her ideas, but she also appears responsible to provide attenuating evidence for the crime. According to McKibbin, "Him" capitalized:

“emphasizes her very patriarchal sense of needing to realize a feminine ideal. She must maintain the pretense that she is the maid mild for him now, if no longer for herself. In her society she is valuable because of her femininity, and this femininity is measured by her fulfilment of (or rather ability to fulfill) the maid mild” (674).

As the ballad continues, Carolyn is found silent and still. (Brooks, 80). The inability to express her suppressed emotions and the thoughts that repeatedly circulate her conscience, whilst in the Fine Prince’s arms, denote both psychological and physical restriction; the factor that ensures this state, is ironically the person who committed homicide to protect her rights from the so-thought black abuser. The egotistical motives underlying his atrocious deed are taken into account, while the woman lingers as the source of the man’s pleasure.

As far as the comparison between the two mothers is concerned, McKibbin focuses on the self-indulgence and the complete disregard of the black woman’s feelings. She supports the claim by adding that white women’s inferiority to white men, prompted a feeling of superiority towards black women (676). It is nonetheless apparent that this white supremacy well-established hierarchy was accountable for violent incidents in the segregation regime. The example of Carolyn Bryant in the poem represents a woman preoccupied with her personal matter but wordlessly acknowledges the validity of a domineering white man, reverting the personal as political the way female black activists construed it.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, the full-bodied female presence in the Civil Rights movement provided unprecedented dynamic support and assisted in fighting discrimination long after the struggle was over. Organizing and empowering the rallies was one aspect of the women’s effort.

Another one was using the page as a field of action, where they could communicate their everyday experience as second-class citizens or simply silenced weak characters. Literature used as vehicle for social justice, addressed the intellect and became valuable heritage or rather a manner to elevate racial trauma and integrate it into a timeless form of art.

9. Works Cited

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Bronzeville Boys and Girls. Harper & Row, 1956.

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Selected Poems. Harper & Row, 1963.

Shange, Ntozake, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf, Batnam Books, 1986.

Youngblood, Shay. Black Girl in Paris. Riverhead Books. 2000.

Youngblood, Shay. The Big Mama Stories. Firebrand Books. 1989.

Christian, Barbara. Black women novelists: the development of a tradition, 1892-1976. Greenwood Press, 1980.

Crawford, V., Rouse J. et al. Women in the Civil Rights Movement: .Trailblazers and Torchbearers, 1941-1965. Indiana University Press. 1993. Google Scholar.

Dixon D., Houck D. Women and the Civil Rights Movement 1954-1965. University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Giddings, Paula. When and where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. HarperCollins Publishers, 1984, Caringlabor.wordpress.com (data di ultima consultazione19/10/2021)

Littlewood, McKibbin M. “Southern Patriarchy and the Figure of the White Woman in Gwendolyn Brooks's “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon””, vol. 44, no. 4, winter 2011, pp. 667-685. Jstor (data di ultima consultazione19/10/2021)

Richard, Jocelyn. A thematic exploration of for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange. University of Maine, 2001. digitalcommons.com (data di ultima consultazione19/10/2021)

Robnett, Belinda. How Long? How Long? How long? How long? : African-American women in the struggle for civil rights. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Rousseau, Nicole. “Social Rhetoric and the Construction of Black Motherhood”, vol. 44, no. 5, July 2013, pp. 451-471. Jstor (data di ultima consultazione19/10/2021)

Shange, Ntozake. Interview with on Gene Shalit “for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf”.” NBCToday Show. NBCUniversal Media. 8 July 1976. NBC Learn. Web. 15 May 2017.