Sylvia Plath's descriptions: selfhood and femininity in her poetry

Zoe Tsaousaki

Zoe Tsaousaki analyses the representation of selfhood and femininity in some of the most famous works by Sylvia Plath, such as Cut, The Bell Jar and Ariel.

1. Introduction

2. The female condition in 'Cut'

3. 'The Bell Jar' and the female liberation

4. Discovering the feminine identity in 'The Bell Jar'

5. Ariel and its female persona

6. The thematic of the 'White Godiva'

7. Conclusions

8. Bibliography

1. Introduction

Sylvia Plath is best known for her distinctive work among contemporary poets, her exceptional temperament, and her adventurous life. Instead of drawing conclusions about how Plath's mental health affected her work and self image, this essay will focus on Plath's perception of selfhood and femininity. In other words, avoiding biographical fallacy, a more objective observation should take place. The literary work under analysis will vary across genres, focusing on her later poetry, to demonstrate consistency or several changes concerning these ideas.

In her poem Cut, Plath speaks of an injured self and a traumatized particle of the protagonist. This can be a general statement about existence. To interpret such a viewpoint, a later publication of Kirby Farrell can be consulted. There seems to be a greater connection between the vulnerable, hurt, individual and collective traumatic experience, after all. Farrell states: “Whatever the physical distress, then, trauma is also psychocultural, because the injury entails interpretation of the injury” (Farrell 7)

Indeed, the injured woman enquires about the nature and extensions of the incident. He furthermore argues that such explanations are deeply influenced by the particular cultural context (Farrell, 7). The poem justifies such a claim since it is about a “Kamikaze man”, “Ku Klux Klan” etc. Moreover, Plath’s poem is developed in a layered manner: there is a part concerning the subject in distress and another one narrating the history of groups in a similar situation. In an unexpected apostrophe, Plath refers to her cut thumb, as her homunculus (Plath, 25), introducing the idea of a self under an observing scope. At this point, we come across literary evidence of a divided consciousness: a soul separated to a subject and an object status. Therefore, the self is seen as multicentered and “ill” (Plath, 25). As far as the “red plush of blood” (Plath, 26) is concerned, despite the phrase’s metaphorical value, is a vehement evolution and demonstration of a bleeding self. It is the effort, intended or unintentional, to draw attention to the trauma, to share individual needs and fears that spread to the public sphere as an instance of common experience of dark historical events. According to Herman, who is supporting Holocaust survivors’ opinion to confront evil, “the conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma” (Herman qtd. in Farrell, 15)

Gender ideas are not extensively touched upon, except for a couple of points: “Dirty girl” is the only phrase which outspokenly refers to the gender.

2. The female condition in 'Cut'

In her poem Cut, Plath speaks of an injured self and a traumatized particle of the protagonist. This can be a general statement about existence. To interpret such a viewpoint, a later publication of Kirby Farrell can be consulted. There seems to be a greater connection between the vulnerable, hurt, individual and collective traumatic experience, after all. Farrell states: “Whatever the physical distress, then, trauma is also psychocultural, because the injury entails interpretation of the injury” (Farrell 7)

Indeed, the injured woman enquires about the nature and extensions of the incident. He furthermore argues that such explanations are deeply influenced by the particular cultural context (Farrell, 7). The poem justifies such a claim since it is about a “Kamikaze man”, “Ku Klux Klan” etc. Moreover, Plath’s poem is developed in a layered manner: there is a part concerning the subject in distress and another one narrating the history of groups in a similar situation. In an unexpected apostrophe, Plath refers to her cut thumb, as her homunculus (Plath, 25), introducing the idea of a self under an observing scope. At this point, we come across literary evidence of a divided consciousness: a soul separated to a subject and an object status. Therefore, the self is seen as multicentered and “ill” (Plath, 25). As far as the “red plush of blood” (Plath, 26) is concerned, despite the phrase’s metaphorical value, is a vehement evolution and demonstration of a bleeding self. It is the effort, intended or unintentional, to draw attention to the trauma, to share individual needs and fears that spread to the public sphere as an instance of common experience of dark historical events. According to Herman, who is supporting Holocaust survivors’ opinion to confront evil, “the conflict between the will to deny horrible events and the will to proclaim them aloud is the central dialectic of psychological trauma” (Herman qtd. in Farrell, 15)

Gender ideas are not extensively touched upon, except for a couple of points: “Dirty girl” is the only phrase which outspokenly refers to the gender.

3. 'The Bell Jar' and the female liberation

The Bell Jar, Plath’s first novel, was published in 1963, just a year after the previous poem. Following the plot of the novel, the reader meets Esther, quite an unusual character; her “mother’s concerns for appearances and her stoical practicality strike the daughter as an inhuman, and unfeminine obliviousness of subjectivity.” (Williamson, 30)

That is to say that the young woman has been raised in such an environment where her selfhood has already been examined. Williamson’s account of Laingian concepts presents relevant aspects: distancing one-self from the others and objectifying them, “insincere compliance” and the formation of a “false self”. Esther attempts to flirt, while her mind dreams of archetypal lovers (Williamson, 32). Despite the idea of a hidden self and its protective façade, the recurring motif of a bleeding persona soon appears. Esther’s intercourse with Marco ends up in a “blood-flood”, which unlike in Cut is not one-sided. Williamson argues against the randomness of the event, as not adequately supported by the narrative or Esther herself. “[T]he “rite” has found its proper “epiphany”” he states, oozing a note of catharsis, since the idea of uncontrollable bleeding presents a damaged, torn individual. Plath reinvents the bleeding self in an impressive manner, bravely renouncing the female body as the main focus of the intercourse. She is not an objectified source of pleasure – a part of the self destroyed by insecurity as described by Laing - but capable of action and liberation.

4. Discovering the feminine identity in the 'The Bell Jar'

Apart from sexuality, Esther discovers other parts of her identity. “Her first “mad” action is a repudiation of the self that belongs, or wants to belong to the New York environment”

claims Williamson, observing the riddance of the woman’s clothes. That decisive moment, the unconscious claims its own centrality and suppresses substantial parts of Esther (Williamson, 41), dehumanizing her. As Williamson puts it, the character wants to dig into “the uncharted interior of the self” (Williamson, 42), and ends up canceling her real self in favor of the numinous ones. Esther distinctly says: “It was as if what I wanted to kill wasn’t in that skin or that thin blue pulse jumping under my thumb, but somewhere else, deeper and a lot harder to get at” (Plath qtd. in Williamson)

This idea refers to existence as a whole and not its physical representation (Williamson, 42); Esther’s suicidal tendency reveals a separation between the understanding of selfhood and a prismatic self-perception, fragmented, which reflects her real image as well as her shadowed, “most beautiful thing” (Plath) –her unconscious. While reading The Bell Jar, one encounters several representations of sexuality and femininity. Esther is desperately trying to have a normal relationship, even though she is cynical. According to Janice Markey “There are some poems in which Plath seems to have believed in the possibility of a meaningful heterosexual relationship” (Markey, 45)

The female character initially tries to settle for her average school relationship, which turns out even more disappointing. An actual rape follows, bringing to her final intercourse with Marco, which itself leads to an “epiphany”. Esther also trusts and opens up to Dr. Nolan who, as her psychiatrist, has a different, profound insight “Then she said, “Tenderness.” That shut me up” (Plath qtd in Markey, 56)

Markey argues that “Plath was comparing her own thoughts on the subject with what had been ingrained in her by the social mores of the time.” (Markey, 57)

This is probably the main reason why in The Bell Jar Plath rejects standard relationships, either straight or lesbian but encourages Esther’s connection to Dr. Nolan. Even though Esther is not able to find wholeness and completion in a relationship, it is possible to experience the whole self. She does so in the ski-run and where there is an “inrush, the implosive pressure of reality” (Williamson, 62)

Williamson supports that for Plath “poetry is a kind of sacred space, not quite in real experience, where contradictions elsewhere felt to be irreconcilable… coexist and the psyche feels momentarily whole” (Williamson, 63)

Even the cynical, depressive Esther is taken aback by such a feeling, promoting positive ideas about the existence of a conscious, fulfilling experience.

5. Ariel and its female persona

Another work that belongs to the later poetry of Plath and is worth studying is Ariel, in which the poet uses the striking term “God’s Lioness” to describe the poem’s persona. The term has been used in Prudah and according to Caroline Barnard it represents the theme of “oppression and release”, while the characterization refers to “that part of herself, which rages for release” (Barnard, 100)

Therefore, at this point, the audience witnesses a strong, composed self, that also considering the name Ariel and its biblical meaning, seems as if the woman, endowed with great strength, will endure tribulation but eventually be rewarded. Markey supports that in Ariel, there is a crucial change, one we do witness in Plath’s later poetry. “The movement is a positive one, away from blockage, from “stasis in darkness” to the speaker’s freeing herself from “Dead hands, dead stringencies.”” (Markey, 62)

The self this time is described as vigorous and dynamic, starving for change and capable of liberation. Despite having endured a great ordeal, the woman can and will be reborn. Markey takes up a different perspective: while most critics claim that this rebirth takes place through death, he believes that it happens “through the most active form of participation of life itself, physical intimacy with another person” (65)

This conceptualization leads to the idea that even though the individual is able to alter its life dramatically, the process may not be individualistic, a self-absorbed reaction or a breakdown. Even though the need for childbirth was a prominent and recurring issue in Plath’s early poetry, in her later works “it has been replaced by a woman’s struggle to attain autonomy and an authentic identity” (Markey 68).

6. The thematic of the 'White Godiva'

A “White Godiva”, a resurrected self or simply a decisive, strong, enlightened character is central to the contemporary poets’ support of individual improvement, which can productively participate in the re-making of the devastated American society of their time. The description of a potent self could not be more obvious than in this case, where the person itself becomes his or her own savior. Away from a messianic hope to be saved or from the presence of children as a source for consolation, the individual moves to a realistic, controlled response. The woman’s endeavor in the poem is possible, especially when she decides to change for herself, although maybe with the support of others. Mari Ellis Dunning in her article speaks of an earthbound persona abandoned in favor of an ethereal one. She also supports that for most of Plath’s poetry the body and the mind are drawn and held together, since the protagonist seeks to escape her own body. Dunning specifically argues: “On the contrary, ‘Tulips’ and ‘Getting There’ demonstrate the speaker’s determination to establish herself through escaping the body. Similarly to ‘Lady Lazarus,’ ‘Getting There’ suggests a delusional belief that death will result in a better life, a recovered sense of self, and elevation to a religious state of being.”

We easily come to a similar understanding of Ariel, especially if we rethink the meaning of the term “White Godiva” as well as lines 28-31: a suicidal flush in the beginning of the day is a potential symbol of regeneration and revitalization. Tim Kendall characterizes the Ariel works as ‘poems of becoming rather than being. Their cycle of becoming, through death and rebirth, is inexorable, and must be constantly repeated, without ever settling on a stable, monolithic identity.’ (Kendall qtd. in Dunning)

This idea is very evident through Ariel itself, since the protagonist takes several forms that are open to interpretation. The poem specifically gives a first and more distinct name for the woman, which is “God’s lioness”, and moves on to call her a “White Godiva” and allow self-descriptions such as “I am the arrow” (Plath 33-34). Plath’s ability to capture the fluidity of identity within a single work is impressive and so is her endless repertoire of metaphors in the taunting journey of a constant identity rediscovery. Even on the outset, while reading Ariel, one can suggest the fusion of a wide variety of features. Mitchell states that “Plath reinforces the identification between the animate and the inanimate to such a degree that the distinction now becomes erased” (Mitchell, 120)

A detailed observation of the metaphors reveals a certain decrease in the spiritual aspect. It is as if we see some light shed on different parts of the soul, which from the grandiosity of “God’s lioness” moves to confronting the practicality of the arrow, until the persona reclaims its identity. This forthcoming image of selfhood is maybe what the momentarily whole of the psyche felt like for the poet. In Ariel, an ever transforming woman, the psyche becomes the subject of interrogation, which is quintessential for her own radical change. The female character is central again, especially since the idea of raising a child is being mentioned along with suffixes such as “lion-ess” or “God-diva”. What Plath seems to support, is non conformity in the field of sexuality as well. “[A] reading on the way social discourses on sexuality in a culture of gender inequality is seen to influence, mainly negatively, the subject's individuality and the interpersonal relations of intimacy in Plath's poems” suggests Balbi. Esther too, in The Bell Jar, is not fully satisfied with any of her options, and for her the most profound meaning of life is provided by genuine, exciting, overwhelming experiences. To rephrase it, the model of a housewife of the era is not sufficient for Plath's brilliant mind, who in Cut very ironically speaks of a thrill and a celebration in her restricting kitchen. What is more, as Barnard reminds us, “Shakespeare’s Ariel is captive by her master Prospero” (99)

Inequality and oppression are the key ideas here, which are providing substantial foundation for social discourse tangling human relationships. According to Barnard, “Ariel then is poet, rider and horse; she is a swift indomitable presence galloping unflinchingly ahead; and she is an androgynous spirit assuming the form of anyone, or anything, who is oppressed and yearning for freedom” (101)

The most common literary connotations, when representing a horse or a lioness, are energy, physical prowess as well as respect in an natural hierarchy. Plath seems to be aware and agreeing with these notions, since in her poem the motherly figure that a lioness can represent, is silenced by her will to gain autonomy: “The cry of the child melts in the wall” (Plath, 33) she writes, searching for more personal space.

7. Conclusions

To summarize, the individual in her poetry is multiple and complex, usually a woman, trying to understand, discover and cope with how selfhood performs rather than having to perform it. As we have seen, gender plays a crucial role in this kind of introspection. Nevertheless, there are some traits or symbols that are typical of Plath’s personas and this is the reason why there is so much discourse about biographical elements penetrating her work. Reading this kind of poetry promotes thinking in terms of one’s own experience, trying to put the poet’s biography on a secondary level, and helps enjoying the works for the sake of pure talent and also for the soul she has masterly poured in them.

8. Bibliography

Balbi, Alita Fonesca. Gender and Sexuality in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath. Federal University of Minas Gerais. Http://150.164.100.248/poslit/08_publicacoes_pgs/Em%20Tese%2017/17-2/TEXTO%203%20ALITA.pdf (data di ultima consultazione: 06/08/2021)

Dunning, Mari Ellis. Sylvia Plath’s Recovery of Selfhood in Ariel – ‘Getting There’. 2013. https://mariellisdunning.cymru/2013/11/01/sylvia_plaths_getting_there_analysis/ (data di ultima consultazione: 06/08/2021)

Farrell, Kirby. Post-traumatic culture: injury and interpretation in the nineties. The Johns Hopkins University Press.1998.

King Barnard, Caroline. Sylvia Plath. Twayne Publishers. 1978.

Markey, Janice. A New Tradition? The Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Adrianne Rich: A study of Feminism and Poetry. Peter Lang. 1988.

Mitchell, Paul. Sylvia Plath: The Poetry of Negativity. University of Valencia. 2011.

Plath, Sylvia. Ariel: The Restored Edition. Faber and Faber. 2004.

Williamson, Allan. Introspection and Contemporary Poetry. Harvard University Press, 1984.

Foto 1 da diegoalvera.it

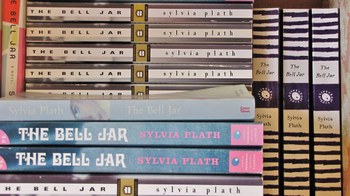

Foto 3 da culturificio.org