Strangers within our gates: threshold figures in American literature

Manuel Acquisti

A compelling view on some of the most ambiguous figures in all of the classic Angloamerican literature, their struggles for acceptance and their self-recognition as unique characters.

1. Introduction:symmetries and uniqueness

2. Growing Pains: the Emily Carr experience

3. The Last of the Mohicans and the virtues of the double

4. The compelling oddities in Uncle Tom’s Cabin

5. The dangers of individualism: Leonard Cohen and the New Jew

6. Conclusion

7. Bibliography

8. Sitography

1. Introduction: symmetries and uniqueness

Plato said that the original human being was a hermaphrodite, the original person was two halves, then these got separated. That’s why everybody’s always searching for their other half. Except for us. We’ve got both halves already.

This is what Zora tells Cal/ Calliope, the protagonist of Middlesex (2013) who ran away from their family because they felt like a monster and a freak for being a hermaphrodite. Zora makes them feel less lonely and weird. Cal finally feels understood by someone who shares their duality or, as W.E.B. Du Bois calls it in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), twoness, in this case two genders, their duplicity that dooms them to belonging to two realities, and yet not belonging entirely to either of them.

This condition does not make them outsiders but rather in-between figures, characters on a threshold. Cal’s twoness is an extreme one that does not only exist on a psychological level but also on an anatomical one; but threshold characters can experience their twoness in various ways, connected to race or cultural background for instance.

While reading some novels and other works belonging to different literary genres from both American and Canadian literature, it struck me to find such recurrent theme as the one of the threshold figures. Analyzing them closely, I found a very peculiar condition humaine in them. They seem to have a key function in a multicultural society, such as the American melting pot and the Canadian mosaic; they act as a link, a go-between, a bridge between different realities, understanding them better thanks to their twoness. As Du Bois says, they develop a double-consciousness which is the key to understanding both sides. However, this does not make it easy for them to fit in but actually constitutes an obstacle, an unease that makes them feel even more left out than a sheer outsider, belonging to many, yet no social group, being “strangers within their gates”. Thus they hanker for a way out, for peace, for a place at the end of those gates, for A Home at the End of the World, we shall say, where Michael Cunningham’s characters, who also find themselves on a threshold because of their sexual orientation, illness or rebellious stands, find a solution, even if it is temporary.

The three protagonists Jonathan, Bobby, and Clare leave NYC to move into a house near Woodstock, the place where they can be themselves. Bobby tells Clare “what’s not to feel good about? We’re something now.”, which means they are building an identity, a yet-to-be-defined one but still an identity that they could not shape within the society’s gates. It is again Bobby who states “What binds us is stronger than sex. It is stronger than flesh…Only we can be ourselves and one another at the same time.” The trio is experimenting, desperately searching for their identities together. Albeit Clare parts from the two men and the experiment is not successful, their case is relevant to acknowledge the unease that threshold figures endure in the common society and their will to find and define themselves elsewhere. Being torn between two realities requires a balance, a fearful symmetry that is most difficult to achieve, sometimes impossible. These characters find different solutions to this issue such as loneliness, the contact with nature and the absence of human relationships, or death.

2. Growing Pains: the Emily Carr experience

The Canadian artist and writer Emily Carr sets a compelling example of a threshold individual even more than the others I will talk about since she is not a fictional character and her real life experiences may be of a more immediate understanding than the ones made up by different authors for fictional characters.

In her autobiography Growing Pains (2009), Carr first relates her upbringing in Victoria, British Columbia, in a family with a strong affiliation with England, a family where she felt “[she] was the disturbing element”. Carr manifested her otherness very early as a child, not always feeling part of her family. She wasn’t an outcast but a different insider, a go-between member of the Carrs.

She then felt this way many other times in her life traveling to London for instance where she went to study painting. In England she felt disappointed, alone and was called “a stranger within our gates” by her host Brother Simon. She was a white woman in London who

“was not English, but she was nearer English than any of the others. She had English ways, English speech, from her English parents though she was born and bred Canadian”.

She was reminded of this, her otherness, many times throughout her permanence in London and wrote, “I knew I was not a nice person. I knew I did not belong to London.” where “nice” means English.

A very particular passage of the autobiography takes place in the chapter Are you saved?, where Carr writes of a dialogue she had with an English woman; “Are you saved?” asks the woman, to which Carr replies “I… I… don’t know” so the woman goes back “That settles the matter, you are not!” (Carr, 2005:161). The woman enunciates a Last Judgment; she is condemning Carr and all threshold individuals to despair, drawing a sharp line between the saved ones and the ones who are not.

This episode vividly recalls the one in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain when the young Huck, deciding to not deliver the slave Jim to the authority, says “All right then, I’ll go to hell” where Huck, just like Carr, is not saved and does not wish to be saved by a society he does not belong to, or not entirely at least.

Carr eventually left England and headed back to Canada where she established a vital relationship with the Nuu-chah-nulth people on the west coast of Vancouver Island which led her to create her aboriginal paintings. She states:

Indian Art broadened my seeing, loosened the formal tightness I had learned in England’s schools. Its bigness and stark reality baffled my white man’s understanding. I was as Canadian-born as the Indian but behind me were the Old World heredity and ancestry as well as Canadian environment. The new West called me, but my Old World heredity, the flavor of my upbringing pulled me back. I had been schooled to see the outsides only, not struggle to pierce. (Carr, 2005:257)

With this statement Carr expresses what it is like to be stuck in the middle and not being able to choose one side over the other. She is a white woman but also has an innate empathy with First Nations. She does not belong to a white European world, or better she partly does, but she also is not a Native. Carr found her balance, accepted her condition as a stranger within society’s gates by being an artist, dedicating her life to nature, and choosing to never get married. This is a solution that worked for her and also partly applies to another character that I want to discuss in this paper that is Hawk-eye in the novel The Last of the Mohicans.

3. The Last of the Mohicans and the virtues of the double

In the novel by James Fennimore Cooper, the scout Hawk-eye perfectly embodies the condition of a threshold figure as he is a white man who has been raised and taught by the Native-American Chingachgook who treated and nurtured him like his blood son Uncas. Hawk-eye has a deep knowledge of the Natives’ culture, beliefs and traditions just like he knows the ones of the white settlers.

He does not refuse his whiteness but actually acknowledges it throughout the whole novel calling himself “a man without a cross” because his blood is white and he is not the product of miscegenation unlike Cora Munro. This prevents him for perpetuating cultural appropriation and signifies his self-awareness: he knows he is different from Uncas and Chingachgook, internalizes it and accepts his function as a link between white people and Native Americans.

“If you judge of Indian cunning by the rules you find in books, or by white sagacity, they will lead you astray, if not to your death” (Cooper, 2009:251) says Hawk-eye in chapter XX to Major Duncan Heyward, a white British military man, when he wants to decide for the whole group to keep moving, thus risking a conflict with the enemies.

Heyward is used to being in command, to rule and guide the mass, but in a foreign, unknown land such as the Upper New York wilderness in the 18th century, he must leave the job of the guide to Hawk-eye, a go-between man who knows that a European mentality cannot be useful and actually may become deadly if adopted in this context. Here the scout shows how witty and wise he is and how he can find the best solutions thanks to his knowledge of the two cultures. He masters both and makes the best choice.

Despite his fundamental function in the novel, from guiding, to teaching, to rescuing others who are in danger, Hawk-eye seems fated to be alone. He does not have a romantic interest but simply remains a wise guide that finds his peace in nature.

In the end, when Uncas dies, he is left with only Chingachgook, who is aged and will pass away soon, so one can imagine him being completely alone, a sort of eremite in the woods. That can be interpreted as his balance, his found fearful symmetry; a threshold man who does not properly fit anywhere and turns to nature to find his dimension like the Canadian artist Carr.

4. The compelling oddities in Uncle Tom's Cabin

Just like Hawk-eye, Uncle Tom in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2005) by Harriet Beecher Stowe tries to juggle between two realities, the white world and the black one, but unlike Hawk-eye he belongs to the minority, for he is after all a slave. A “privileged” one if we will, as his master Shelby and his wife treat him nicely and trust him to look over the other slaves. He is also a husband and a father which means he has been blessed with a family, something very rare for a slave.

Tom is aware of his position in the social ladder but does not try to change it, does not fight the system nor does he hate on white people. He actually respects them and deals with them to the point which in chapter V he accepts Shelby’s surprising decision to sell him by simply saying:

If I must be sold, or all the people on the place, and everything go to rack, why, let me be sold. (Stowe, 2011:34)

He is disenchanted and acts like a martyr ready to give himself up for his people, which includes both slaves and whites. His behavior comes through as odd, perhaps too idealistic to both the other characters and the reader, making Tom’s psychology very difficult to fully comprehend.

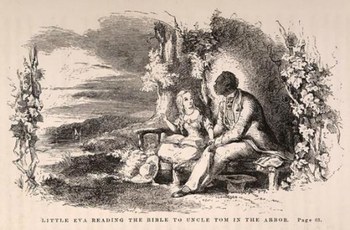

The only other character who does indeed share his psychology is Eva, the young white daughter of St. Clare, Tom’s second master. Eva’s first appearance occurs in chapter XIV where she is described as a “mythological and allegorical being [with] golden hair”, in the same chapter when Tom rescues her out of the river she fell in. The child appreciates Tom’s presence and his singing and she acts innocently, as if she did not realize he is a slave of her family. She also is somewhat different than her family members who do not understand her behavior with slaves. Her mother Marie, for instance, says that

“Eva always was disposed to be with servants [and] somehow always seems to put herself on an equality with every creature that comes near her. It’s a strange thing about the child.” (Stowe, 2011:146).

Eva is so unordinary and odd to her mother that when she asks her to teach the slaves to read in chapter XXII, which signifies to cross a limit, Marie is so bewildered and astonished that she says she is getting a headache as “Marie always had a headache on hand for any conversation that did not exactly suit her” (Stowe, 2011:224).

This phrase sums up the revolution that Tom and Eva bring about: they make unsettling remarks that lead others and the reader to dwell on them and question their positions. They are the ones bringing the change, which in this case is the abolition of slavery.

Unfortunately, they both are too ahead of their time and cannot survive. Tom dies because he refuses to whip other slaves and Eva dies of an illness and both deaths recall Jesus Christ’s ultimate sacrifice for humanity’s sake, namely Eva’s. On her death bed she tells Tom:

I can understand why Jesus wanted to die for us… because I’ve felt so, too… I’ve felt that I would be glad to die, if my dying could stop all the misery. I would die for them. (Stowe, 2011: 233)

In chapter XXII, Stowe reflects on the figure of Eva and, consequently, the one of Tom writing:

“Has there ever been a child like Eva? Yes, there have been; but their names are always on grave-stones… It is as if heaven had an especial band of angels, whose office it was to sojourn for a season here, and endear to them the wayward human heart, that they might bear it upward with them in their homeward flight.” (Stowe, 2011: 222)

Stowe here reflects on the likelihood of such characters to exist because they look very much unlikely to.

What makes Tom and Eva such barely believable characters is that, in a culture that defines itself as Christian, they believe, and act on the basis of this faith.

Both Tom and Eva are supposed to die because the time they live in makes it impossible for them to create a balance and to achieve a fearful symmetry. They are too odd and defy too rooted a crime, the one of slavery that is, to get away with it. Their work is appreciated and admired by the reader and those who lived after the Civil War, but Stowe has to be realistic and knows that they had no place to occupy in Kentucky in 1852. Their fate as threshold figures is the one of death.

Had Tom and Eva lived in a different period, they would perhaps have survived and they would have understood that “[the individual] is not bound to the world as given, that he can escape from the painful arrangement of things as they are” as the narrator states in Beautiful Losers.

5. The dangers of individualism: Leonard Cohen and the New Jew

In this post-modernist work by Leonard Cohen, the threshold figure assumes a new name, The New Jew and he is given a mission:

He confuses nostalgic theories of Negro supremacy which were tending to the monolithic. He confirms tradition through amnesia, tempting the whole world with rebirth. He dissolves history and ritual by accepting unconditionally the complete heritage.

The New Jew is, according to F., narrator of the second part of the book, A Long Letter from F. (1993) , what post-WWII North America needs. He must riot against the established traditions and history not by rejecting them but by blending them with the rest, with other traditions of other cultures. He wants a society in which identities are flexible, ever-changing and contaminated by one another.

The protagonist violently defies the dominant cultures in both Canada and the USA stating: “I want a country to break in half so men can learn to break their lives in half”. He becomes an extremist and a terrorist even, in order to make himself heard. He also yearns for a collective awareness in order to make people realize that nothing is black and white, he “demands revenge for everyone” because no one in a post-WWII North America is “without a cross” since he affirms:

The English did to us what we did to the Indians, and the Americans did to the English what the English did to us.

The role of the victim can be played by the victimizer, too. No one is entirely innocent or guilty but both altogether. These dichotomies that coexist do not exclude each other but actually need the opposite in order to survive and are very recurrent in Canadian literature in terms of metropolis/small town, English/French, landscape/inscape and so on, creating a literature that Northrop Frye in The Anatomy of Criticism (1957) calls the schizophrenic mind.

According to F., everyone in North America is a go-between individual and he urges them all to acknowledge it, to

“think they are Negroes, [because] that is the best feeling a man can have in this century.”

F. wants to reach a fearful symmetry, the one represented by the Canadian landscape that “is together Goodness and Evil, good and bad, is together Life and Death”. As Capone says, “if the symmetry is broken, the forces of the separation of this split balance will be neutralized by a precise predominance” and that is exactly what F. does not want to happen. He is asking for a society that truly acknowledges all its different halves.

If on one hand this ideal society of F. can be appreciated and even adopted, on the other hand, the narrator in the first part of the book, The History of Them All, reminds him and us all of the possible dangers of such society saying to F.:

You’ve turned Canada into a vast analyst’s couch from which we dream and redream nightmares of identity, and all your solutions are as dull as psychiatry

which points out how in a society made up of threshold individuals, all of them necessarily aware of it, it would be impossible to attain any sort of identity, therefore unity and ultimately a society itself.

In Beautiful Losers threshold figures are “whipped by loneliness” because they are inconvenient to a society that functions because it has a predominant thorough culture that does not own up to its impurity, its twoness, its miscegenation, and ultimately to its history.

6. Conclusion

From analyzing these four texts of American and Canadian literature which deal with the threshold figure in different ways, I can state that such characters carry a burden that makes it tedious for them to adapt and fit in a society even when it happens to be a multicultural one. They come through as some kind of tragic mulatto that is doomed to loneliness, despair, ostracism, extremist acts such as terrorism, and even death.

They are not celebrated for their profound insight in what American and Canadian societies are like but rather stranded at the gates. They cannot be categorized, fixed in a definite social group and perhaps this is what is unsettling about them to the eyes of the majority that wants to keep a status quo.

My intention not being the one to romanticize their condition humaine but simply to reflect on and acknowledge their function and treatment in American and Canadian societies, I can say that both countries, notwithstanding their politics of the melting pot and the cultural mosaic, need to have a predominant culture in order to keep the country together tolerating minorities but leaving little space to the ones who are in between, on the threshold.

7. Bibliography

Beecher Stowe, Harriet, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Dover Thrift Editions, 2005.

Capone, Giovanna, Canada il Villaggio della Terra, Patron Editore, 1978.

Cohen, Leonard, Beautiful Losers, Random House, Inc, 1993.

Cunningham, Michael, A Home at the End of the World, Penguin Books, 2012

Du Bois, W.E.B., Of Our Spiritual Strivings, in The Souls of Black Folk, A.C. McClurg & Co, 1903. At: wwnorton.com

Eugenides, Jeffrey, Middlesex, Fourth Estate, 2013.

Frye, Northrop, The Anatomy of Criticism, Princeton University Press, 1957.

Portelli, Alessandro, Canoni Americani: Oralità, Letteratura, Cinema, Musica, Donzelli Editore, 2004.

Twain, Mark, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Penguin Books, 1967.

8. Sitography

Carr, Emily, Growing Pains, books.google.it (data di ultima consultazione 08/08/2021)

Cooper, Fenimore James, The Last of the Mohicans, books.google.it (data di ultima consultazione 08/08/2021)

Picture 1, rachelheldevans.com (data di ultima consultazione 08/08/2021)

Picture 2, decider.com (data di ultima consultazione 08/08/2021)

Picture 3, wnyc.com (data di ultima consultazione 08/08/2021)