The Case Study Site

Ship on the venetian lagoon. Image by Nicola Quirico. CC license available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sacca_degli_Scardovari.jpg

The venetian lagoon, located in the region of Veneto, northeast of the Italian peninsula, is the largest wetland in the Mediterranean basin, encompassing an area of around 550 square kilometres. It is currently an example of a Habitat 1150,[1] that is a coastal lagoon with access to both freshwater inflows and several openings via channels to a saline marine environment (the Adriatic Sea), as opposed to landlocked coastal lagoons. This largely shallow environment of mudflats, marshes, flood lands and channels, has transformed over the past two millennia with increased water levels and flood zones, as well as land reclamation projects around many of the small islands and barrier beaches. The current lagoon is a larger wetland today than it would have been in the Roman period, while the more urbanised coastal and island settlements, such as Venice, date back to the Early Medieval period. The exceptional cultural heritage attached to Venice’s urban fabric draws in tourism to the Italian coast and promotes archaeological investigations of the port town. However, these sites overshadow the earlier Roman settlements and the evidence of occupation dating as far back as the 8th century BC. The largest Roman urban centre on the Veneto coast was located on the north-western extent of the lagoon: Altinum, destroyed in AD 452 by Attila, yet formerly a significant crossroads where sea, land, rivers, and channels met. The choice for such a crossroads within a lagoonal environment draws attention to the potential for these ecosystems in providing valuable resources.

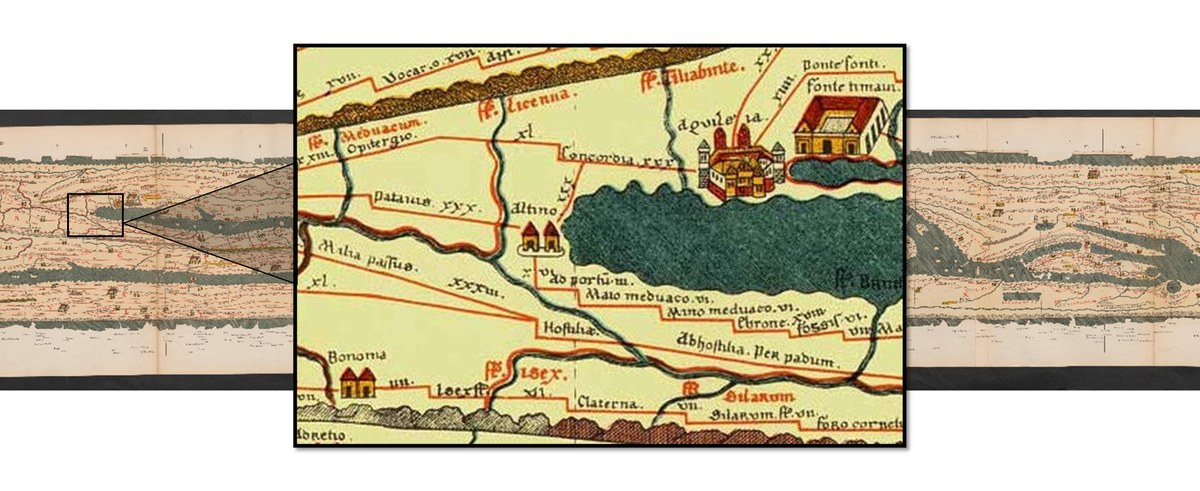

Altinum, was an important commercial port-city in Roman times, connecting Patavium (modern Padua) in the west and Ravenna in the south with Aquileia to the northeast and the eastern territories beyond (the latter two via sea as well as road). It is referenced in the Antonine Itinerary and appears in the 12th-13th century Tabula Peutingeriana (see figure below), itself a copy of a Late- Antique example, which likely predated the destruction of the city in 452 AD. While no lagoon is depicted, several literary sources attest to a tidal lagoon in the region of the Veneti (Livy 10.2.5); describe the wetlands between Ravenna and Aquileia as the Septem Maria, or ‘seven seas’, in reference to the various fluvial outflows (Plin., Nat. 3.16; Hdn 8.7l; Mart. 4.25; Itin. Ant. p. 126); or acknowledge the fluctuating coastline and flooding of coastal lowlands (Vitr. 1.4.11). A vivid and recognisable description is provided by the 5th-6th century AD scholar and statesman Cassiodorus:

‘It is a pleasure to recall the situation of your dwellings as I myself have seen them. Venetia the praiseworthy, formerly full of the dwellings of the nobility, touches on the south Ravenna and the Po, while on the east it enjoys the delightsomeness of the Ionian shore, where the alternating tide now discovers and now conceals the face of the fields by the ebb and flow of its inundation. Here after the manner of water-fowl have you fixed your home. He who was just now on the mainland finds himself on an island, so that you might fancy yourself in the Cyclades, from the sudden alterations in the appearance of the shore… the earth there collected is turned into a solid mass, and you oppose without fear to the waves of the sea so fragile a bulwark, since forsooth the mass of waters is unable to sweep away the shallow shore, the deficiency in depth depriving the waves of the necessary power.’ (Cassiod., Ep. Varr. 12.24. Trans. Hodgkin 1886).

[1] The EU classification of habitats can be accessed in PDF via the following link: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/eunis-habitat-classification/documentation/eunis-2004-report.pdf/download (accessed 16/05/24). Coastal lagoons that have no direct surface access to marine environments are considered lagoons.

The 12th-13th century Tabula Peutingeriana, depicting Altinum. Image is public domain.

The economic contribution of Altinum is briefly discussed, such as the quality of its scallops (Plin., Nat. 32.53) and its wool in the 1st century AD, third only to Apulia and Parma (Mart. Epigr. 14.155); or salt production and fishing in the 5th century (Cassiod. Ep. Varr. 12.24). Some chronological shift is clear, as the popularity of this coast for attracting wealthy Romans to build villas in the region in the 1st century, Martial choosing it as his own retirement destination (Epigr. 4.25), is contrasted by Cassiodorus’ description of the no longer present dwellings of the nobility in the 5th century, since replaced by the ‘scattered homes’ of the inhabitants who ‘gorge themselves with fish’ (Ep. Varr. 12.24).

The historically attested diversity of the economic wealth and types of habitats in the Roman period, make the region a fascinating study in Roman culture and their adaptation to transforming landscapes in the midst of political shifts. The choice of this case study area rests on 3 principles which relate this story:

1) the availability of archaeological and paleoenvironmental data arising from ongoing archaeological investigations, in particular the excavations at the site of Lio Piccolo

2) the availability, in the Museum of Altino, of unpublished fishing implements

3) the need to offer to the local communities of the area, which are historically and economically in Venice’s shadow, a more complete reconstruction of their cultural heritage.

Location of both sites in the northern end of the lagoon. Altinum NW and Lio Piccolo NE. Image from Google Earth CC.

The site of Altinum and the Altino Museum located in the centre, framed by the Sile (N) and Dese (S) rivers.

The site of Lio Piccolo, surrounded by numerous islands and tidal canals.