Why (not) comics?

Comics is a (hybrid) medium/language of its own right, and not a lowbrow genre of either visual arts or literature. Being a “cool medium” (McLuhan, 1964), comics provides low definition sensory data and consequently demands participation and/or completion by the audience.

Thus, it can distract/entertain us with its stories, but also teach us important lessons about the mechanisms of our environment (which comics reflects, but also actively contributes to shape), and its own functioning (due to its self-reflexive nature which interrogates the consumer about the difference between looking and reading). Therefore, as Nick Sousanis (2015) argued, by combining textual and visual literacy, comics can “unflatten” our thinking.

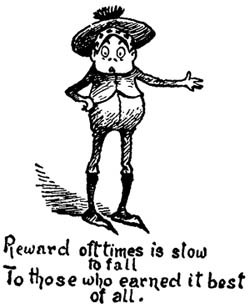

Comics was born in the U.S. in the 1890s in Pulitzer and Hearst’s newspapers giving life to an editorial war for the possession of the rights to the Yellow Kid character. At first glance, this fight might seem trivial, yet it reveals how these two moguls already understood the potentiality of this medium. Indeed, in the twenty-first century comics has branched out from its Sunday paper appearances into myriad junctions of (pop) culture well beyond the United States. Given its ductility, the medium evolved both diachronically (across time) and synchronically, especially diatopically (across space).

Diachronically, comics evolved from strips to comics books to graphic novels to digital comics, web comics, and infinite canvas. Yet, it is worth remarking that each new evolutionary branch of the medium did not substitute the previous one but created its own niche.

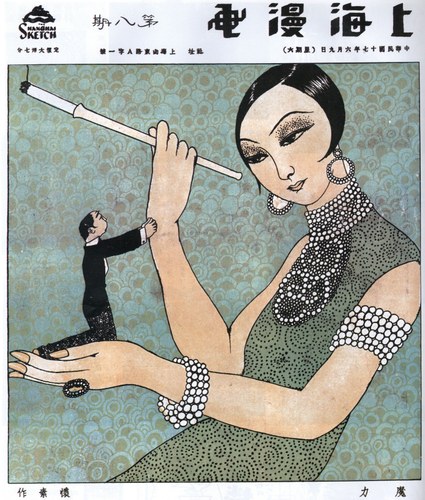

Diatopically, different countries created their own tradition. Outside North American tradition, the two most internationally visible diatopic variants of the medium are the Franco-Belgian Bande Dessinée (BD), and the Japanese Manga, which have their own peculiar genealogy (mixing different traditions and adapting the medium to the genius loci) and development. Even though the origins of Franco-Belgian comics (Bande Dessinée) might be traced to Rodolphe Töpffer’s cartoon strips (this proto-comics lacked speech balloons) of the 1830s, the medium became popular/mature only in the 1930s when it was able to reach a mass audience.

In Italy, the date that marked the birth of comics is December 27, 1908, that is when the first issue of Il Corriere dei Piccoli (the first mainstream publication primarily dedicated to comics) made its debut. The medium also flourished in other European countries (like Germany and Finland, among others), the Americas (including Canada and Latin America), but also Asia, where one can appreciate the (Japanese) manga, (Chinese) manhua, (Korean) manhwa, and (Filipino) komiks, among other traditions. Moreover, in recent years the medium has also been appropriated by First Nations, who have been using it to make their causes visible.

Undeniably, the comics universe embraces a great diversity of genres and readers, giving life to an inclusive and “democratic mash-up” (Chute, 2017). Comics have shaped the imagination of many young people (but not exclusively), and have generated a wide community of aficionados (which encompasses not only nerds and cosplayers, but also writers, poets, gallerists, curators, archivists, students, professors, among others) that massively populates conventions. Comics also invaded other media and spaces, going beyond their frames. They ‘invaded’ the academia, Broadway, Hollywood, museums, galleries, internet, and social media.

The growing power of the medium in contemporary cultural debates is particularly evident whenever censors try to limit the force and diffusion of its content, which relies on the affective power of images.

Given the above, it is no surprise that comics has been studied by a broad range of disciplines and through different approaches. The aim of this group (and the initiatives it promotes) is to expand the knowledge of/about the medium, but also to investigate the role it plays in our societies. Indeed, throughout its history, comics has functioned as an instrument of entertainment, propaganda, but also advocacy, and activism. Many contemporary comics have given voice to marginalized communities through biographical, autobiographical, documentary genres, as well as through fiction, among which the superhero genre (perhaps the most recognizable genre of the medium). Yet, these analyses would be stunted if detached from the material culture of the medium and the participatory practices linked to its diffusion, production, consumption, and sharing.