On writing, publishing and media: a conversation with Wu Ming 4

How two Italian artistic collectives have challenged the mainstream cultural industry during the last thirty years

Pubblicato il 16 ottobre 2025 | Arte e Cultura

Figure 1 - An easy guide for performing the psychic attack Credits: Frame 02:52

Bologna, January 1995. A group of people gathers at 3:00AM and stands in the same pose: the elbows touching, the hands clasped and pressed against their forehead. They concentrate and start obsessively chanting “OM”. They are performing a psychic attack against the enormous renovation project of the central train station, only the last of many inconsiderate renovation projects of Bologna. They act under a single, shared identity: Luther Blissett.

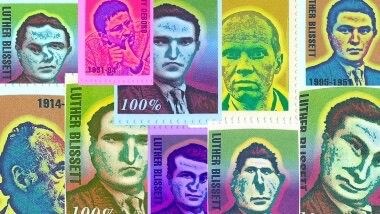

The Luther Blissett Project (from now on LBP) was a collective of artists, activists and performers active in Italy in the 90s that borrowed the name from a former mediocre A.C. Milan soccer player. The choice of the name was never explained by the collective. Anyone could “become” Luther Blissett, simply by claiming their performances (articles, events, provocations) with that name.

Figure 2 - Icons depicting the many imaginary faces of Luther Blissett Credits: https://aboutbologna.it/informati-credi-crepa-quando-luther-blissett-fake-news/

They fought a cultural guerilla against some trends of their time: individualism, unsustainable urban development and media manipulation. The idea was simple: give up your personal identity to join an open, anonymous network without leaders or hierarchies. The LBP ended in 1999 after a symbolic collective suicide (a seppuku), but its heritage inspired many artistic and political collectives, including Wu Ming.

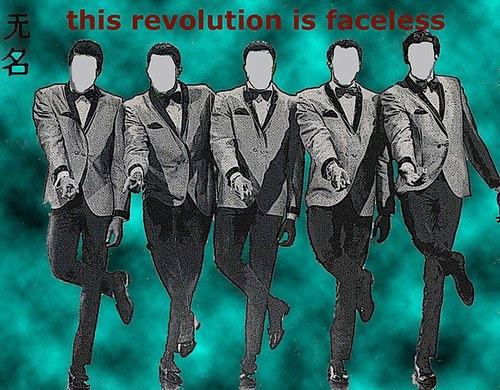

Wu Ming is a group of three writers (originally four) whose name means “Without a Name” in Chinese. Their very name, in continuity with the LBP, reflects the idea of setting aside individual identity to embrace a collective one. They write books together, but they also produce solo works, signing them with a number after “Wu Ming” (currently the members are Wu Ming 1, 2, and 4).

This article explores, through an interview with Wu Ming 4, three aspects of continuity between the LBP and Wu Ming: the fight against misinformation, the radical critique of the copyright system and the practice of collective writing.

The LBP can be seen as a forerunner of an innovative trend in contemporary communication: the use of fake news as a form of political action in the early 90s, in a very different media context from today. Indeed, information has shifted from centralized, identifiable sources to a decentralized, uncontrolled flow driven by social media. This makes fake news harder to detect and more common. Once a subversive tool to challenge institutional narratives, disinformation is now often used by political power to influence public opinion.

In the media context of the 90s, LB used fake news to enlighten the porosity of the mainstream media system. They used provocation and hoaxes against the main information channels to raise public awareness on this matter. As Wu Ming 4 says:

Back in the days of the LBP, we were in an earlier phase than this one: you could fabricate a piece of news, and the media would fall for it. Then you’d come out with the debunking of your own story and self-debunk it, saying: “See how easy it is, right?” Just think how often they do this – they take some material, turn it into a story, and make you believe it – because communication was still very one-way back then.

A useful metaphor to explain this use of fake news is the one of “vaccination”. The aim is to highlight the real interest of the information channels: to publish more and to make news as spectacular as possible. Following Wu Ming 4:

We were spreading fake news on purpose, only to later claim them as such.

And that was a key step for us. It wasn’t about being forgers, it was about being forgers who admitted it, and who explained how the hoaxes were built. Media pranks, tricks, fake news—those were all ways to show how permeable mass media actually were.

Figure 3 - The La Repubblica - Bologna article about the Naomi Campbell prank, 28 October 1995

One of the most famous pranks is the case of Naomi Campbell in Bologna. A Luther Blissett member anonymously called the local newspaper Il Resto del Carlino, claiming to have seen the supermodel secretly entering a plastic surgery clinic. Obviously, it was a fake, but the newspaper still ran the headline: “Top secret surgery for Naomi”, without bothering to verify the claim.

The day after, LB publicly claimed authorship of the hoax, completing the “immunization” process by exposing the lie and forcing the public to confront how easily disinformation spreads. The popular newspaper La Repubblica published an article linking LB to this event.

Contrasting disinformation is still a crucial challenge for Wu Ming. In today’s media context, though, the fight requires a further tool: a wonder injection.

Myths, narratives, stories. For a sphere that isn’t purely rational – of course that’s needed too, debunking is important, no doubt – but it’s not enough. Something else is needed. What we need, as the Americans would say, is a wonder injection. The only way today is to do just that, right? Create stories that are far more compelling than conspiracy fantasies. The wonder injection needs to be told; you need to be better at narrating stories.

The idea is to beat conspiracy theories by proposing better narratives, not by just debunking them. Conspiracies promise to reveal something that no one else will. If that’s the case, instead of only explaining why that is not true, Wu Ming gives us an example:

Then I also need to reveal something to you: Capitalism is the greatest magic trick ever performed. They've convinced you it's natural to live by selling your work. I might not say it outright; maybe I'll tell you by writing a novel, and here's a story that doesn't talk about it at all. But that's the point. I stand by that choice, perhaps less so others. That choice is a path to follow. I understand why debunking isn't enough. And again, fake news has a snowball effect anyway. So, the only way today is to undertake this operation: create stories that are much more interesting than conspiracy fantasies.

Figure 4 - Logo used by Wu Ming between 2001 and 2008 - The phrase "the revolution is faceless" summarizes one of the collective's founding principles: not appearing in person to avoid self-branding.

Challenging prevailing trends in the cultural industry – whether during the LB or the Wu Ming period – has involved not only transforming how stories are told but also reshaping the channels through which those stories are shared. This is why they embraced principles of open access to make cultural production widely accessible.

Since their historical novel Q in 1999, Wu Ming have applied this approach through the copyleft system, which leverages copyright logics to ensure that works remain free to use, modify, and distribute; and that any derivative creations inherit the same freedoms. All their books are freely available on the download page of their blog “Giap”, in different electronic formats.

Wu Ming’s books are also sold by major publishers. Wu Ming 4, talking about the relationship with publishing houses, explains:

Since the foundation of Wu Ming in 2000, we said: these are our conditions and we're not willing to compromise on them: copyleft and not appearing in the mass media with our faces. So, no cult of the author: no talking about us or our personal lives. In essence, denying the idea of the author as a character, which is exactly what’s most popular today. What we observe now is that books are no longer being sold; authors are.

Talking about the diffusion of the copyleft model and its actual value, WuMing4 continues:

We didn't succeed: no one followed us down this path; I don't feel like claiming victory here. For us, it's been a sine qua non condition from the beginning. I don't know of others who write and have chosen this path; it hasn't become mainstream.

Even in the way they produce their books, the idea of working as a group remains central. Indeed, one of the most distinguished features of Wu Ming is collective writing. We must not imagine it as an industrial process, in fact as an artisan activity that synthetizes ideas and different individualities, experiences and prospectives.

Figure 5 - All the blog’s content is free to use under the Creative Commons license

We all started from scratch; we had to come up with our own method. Had one of us already been established, with a clear path, I think it would have been much harder for him to step back or avoid making that fact felt, even unintentionally. Instead, since we were all more like absolute beginners, we managed on our own: we invented a method.

Collective writing, for Wu Ming, goes beyond literary technique: it’s a political and ethical stance. It means learning to listen, to compromise, and to build something together that no single author could create alone. It’s a practice that challenges individualism and reinforces the value of cooperation and shared responsibility.

It’s enriching because you come together to do something, in this case to build a collective narrative. So, once again, it’s not about the self. It’s not about me. It’s a “we” that is the sum of its parts. So, it’s not about denying subjectivity, but rather exalting it within collective work. And in this sense, it teaches you how to deal with others, especially now that the know-how of interacting with others is being lost. Working in a group has been extremely valuable for me over the years. I even learned how to discuss, how to hold back my hyper-critical side – or rather, how to transform it – and how to express things one way instead of another.

Wu Ming remains actively engaged in collective writing, while also organizing workshops, labs, and similar initiatives in collaboration with universities and various cultural or social organizations. In these settings, Wu Ming members take on the role of facilitators, guiding the process rather than directing it. In this way, they continue to promote collective writing as a participatory practice, bringing it to new communities and generations.

The experiences of both the LBP and Wu Ming demonstrate that it is possible to resist dominant cultural dynamics through a coherent and radical approach. Radical in the sense of going to the root of every issue they choose to engage with. Their practices, from media hoaxes to collective authorship, reflect a sustained effort to rethink how culture is produced, circulated, and experienced.

In a system that privileges individual visibility and competition, their method is not idealistic but it proposes a concrete strategy to develop alternative cultural models. To conclude with the words of Wu Ming 4: “It’s important to keep trying, through practice, not theory – just like during the Luther Blissett Project – to prove that things can be done differently."

A key contribution to the development of this article was the interview with Wu Ming 4, conducted in Bologna on May 7, 2025. The main sources consulted include the official archives of the Luther Blissett Project, the Wu Ming collective’s blog Giap, as well as a wide range of newspaper articles and documentaries addressing these subjects. Additional insight was provided by notable academic works such as La narrazione come mitopoiesi secondo Wu Ming by Marco Amici; La “funzione autoriale” tra lotta politica e branding. Alcuni aspetti dei casi Wu Ming e Scrittura Industriale Collettiva by Beniamino Della Gala, and L’informazione come scandalo. Dall’iperrealtà dell’industria dell’informazione alle fake news del sistema mediale ibrido by Marco Binotto.

Articolo a cura di Eleonora Boin, Miriam De Giuseppe, Luca Francalancia, Marco Moschini e Davide Santoriello.