It is (not) easy to have children. Koreans know it too well.

As fertility rate drops, it’s interesting to investigate how this phenomenon is intertwined with gender inequality. In South Korea the issue is more related to the social environment than you’d think.

Pubblicato il 21 ottobre 2025 | Gender Studies

Di Michela Loru, Sara Manni, Gabriele Parmeggiani, Liu Zimeng

A busy street in Seoul, South Korea (nylonpink.tv/Pinterest)

South Korea’s birth rate dropped to a new low this year, remaining the lowest in the world once again.

As reported by Korea's official national statistical organisation (KOSTAT) last February, the average number of children of a South Korean woman during her lifetime fell from 0.78 in 2022 to 0.72 the following year: a decline of nearly 8%, reaching figures under 1 child per family.

The rate is well below the average of 2.1 children the country needs to maintain its current population of 51 million.

You might be wondering how South Korea got to this point. Motivations are complex. The most prominent reason is to be found in the country’s competitive environment and career-centred mentality.

Other impactful factors are not only the high costs of both education and childcare – and every other cost that comes with raising children – but also housing expenses.

All governments have been pursuing policies to encourage young families to have children for some time but with little success. However, little to no measures were taken to tackle what many South Korean women believe to be the cause of this demographic crisis: the difficult situation women have to face in their workplace after childbirth.

How did everything start?

The demographic crisis is a major threat to the economic growth and the sustainability of welfare systems in many economically developed countries. This is particularly true in South Korea, where it has been defined as a national emergency.

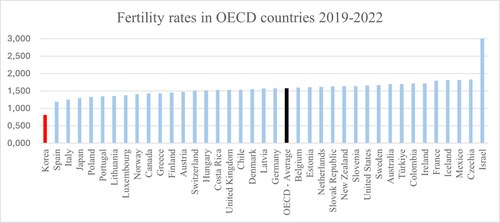

South Korea’s birth rate has been dropping constantly, confirming its position as the lowest among OECD countries. If the low fertility rate persists, the population of Asia’s fifth-biggest economy is projected to halve by the end of this century, Reuters finds, and in the next 50 years more than half of South Koreans will be over 65.

Based upon the latest data available from OECD.org (data.oecd.org)

The current administration, led by the conservative president Yoon Suk Yeol, has made reversing the falling birthrate a national priority, The Guardian reports.

The beginning of this issue dates to when South Korea went from counting five children per family at the end of the Korean War to under two in the 80s. The government saw this as alarming and began to implement investments to encourage couples to have more children.

Since 2006, South Korea has spent more than 280 trillion won ($211bn) in childcare subsidies, babysitting services, support for infertility treatments, and other such measures.

But the problem seemed to be more intricate, and the solutions provided by the government were not as effective. Thus, they opted for a more comprehensive approach in the early 2000s by establishing the Presidential Committee on an Aging Society and Population Policy to enact direct support to families, including childcare services.

In recent years, in-kind help with a more customised approach has been promoted. Financial inducements have been given to married couples who have – or wish to have – children. To mention a few: monthly subsidies, free transport services, medical expenses coverage for some treatments, and preferential paths to obtain public housing.

Since these initiatives found little success, less conventional strategies were attempted, such as exempting men who have three children before turning 30 from mandatory military service and hiring babysitters from Southeast Asian countries; but even organising “blind dates” for single people was not enough.

A problem rooted in society: work-life (in)balance & skyrocketing expenses

As reported by The Guardian, financial and other inducements are failing to convince couples who have to deal with obstacles such as rising child-rearing costs and property prices.

Educational costs also play a significant role: according to a recent study by the Chinese demographic research institute YuWa, South Korea is the most expensive country in the world to raise children.

Despite all the economic incentives promoted by governments in the last twenty years, the sheer amount of money necessary to make it possible for a child to attend one of the best universities in the country is unsustainable for many families.

It is very common for families to invest in extracurricular activities: this phenomenon is tied to the ultra-competitiveness promoted in schools, universities, and workplaces in Korea.

As a matter of fact, in the past few decades, life in the country has become much more career-oriented, with longer shifts and fewer vacation days. By following this path, South Korea became the workaholic society we know today, with extremely competitive pressure in the workplace.

It’s quite easy to understand how this characteristic does not impact positively on the birth rate. For many Korean women, Al Jazeera states, this aspect of Korean culture means that taking time out to have a baby is too much of a risk.

But is that truly all? South Korean women might disagree

Besides, taking time off for women is even riskier in a country that already has one of the worst gender pay gaps in the OECD: Reuters underlines how a Korean woman earns about two-thirds of what a man does. Looking at the 2023 Global Gender Gap Report released by the World Economic Forum, South Korea ranks 105th out of 156 countries.

The Guardian states how, according to experts, the difficulty working mothers have juggling their jobs with the expectation that they are mainly responsible for household chores and childcare is one of the obstacles responsible for the low fertility rate.

The situation for women in South Korea, especially those working, is not ideal. Mothers face significant difficulties in obtaining promotions and generally experience much discrimination.

Furthermore, traditional gender roles, which are still very dominant in the country, dictate that mothers should primarily take care of children. In the last 50 years, Korea's economy has grown rapidly, increasing women's participation in higher education and the workforce. However, the roles of wives and mothers have not evolved at nearly the same pace.

As a result, many find themselves forced to quit their job after having children and must face the decision to either have a successful career or foster family, as a BBC News investigation led by correspondent Jean Mackenzie finds.

This happened to one of the women interviewed by BBC News, Jungyeon Chun, who shared how “I had been well-educated and taught that women were equal, so I could not accept this.”

Another interviewee, Stella Shin, explained that “mothers need to quit work to look after their child full time for the first two years, and this would make me very depressed," she said. "I love my career and taking care of myself.”

Both men and women are entitled to a year's leave during the first eight years of their child's life. However, in 2022, only 7% of new fathers used some of their leave, compared to 70% of new mothers. Fathers who actively participate in daily childcare are a rarity.

You might be wondering what exactly causes such a large gender wage gap: it essentially comes down to three main causes.

First, as already mentioned, culturally, it is expected that women should take care of the household in addition to working for long hours, making it hard for them to keep up.

Second, since the 90s, women have been concentrated in low-paying, insecure jobs with little protection: according to Time, South Korea has the highest share of late-middle-aged women with temporary jobs in the OECD.

And third, the rise of low-quality part-time jobs keeps women from fully joining the workforce, maintaining inequality alive.

Due to declining birth rates, one-third of kindergartens and daycare centres in South Korea are expected to close by 2028. (woodleywonderworks/flickr)

Feminism and politics: a complex history

South Korea's conservative society, influenced by historical factors like Confucian values and centuries of isolation during the Joseon Dynasty, initially hindered the consideration of women's issues.

Consequently, the feminist movement emerged relatively late but has been marked by radical activism. Despite significant contributions to democratisation since the 80s, including recent successes such as the MeToo movement, more extreme factions like Megalia and 6B4T have faced backlash and male hostility.

This highlights the particularly challenging landscape of gender activism in the country. Integrating feminist goals into a nationalist approach is complex due to Korean society's politicised and conservative nature, making progress challenging.

For example, during the 2022 presidential election in South Korea, contrasting attitudes toward feminism were observed among voters aged 20-30. While female voters showed balanced preferences for both candidates, Yoon Suk Yeol and Lee Jae Myung, male supporters of Yoon displayed higher opposition to feminism.

Media reports suggested that Lee strategically shared "anti-feminist" content to attract young male voters and narrow the gap with Yoon.

Criticism arose regarding political leaders exploiting anti-feminist sentiments for electoral advantage, exemplified by Yoon's promise to introduce a false accusation clause in the "Sexual Violence Punishment Act," potentially endangering progress on gender issues.

How does this mirror internationally?

But the demographic crisis is not an exclusive Korean issue: birth rate is declining worldwide. As reported by the Financial Times, over the past 50 years, the global fertility rate has roughly halved to 2.3. In most advanced economies it is already well below the replacement rate of 2.1.

According to Our World in Data, three major reasons can be identified for the rapid decline of the global fertility rate: the empowerment of women, who now have increased access to education and career possibilities; the declining rates of child mortality; and the rising costs of raising a child.

The declining birth rate, however, is not entirely bad news. Stein Emil Vollset, professor of Health Metrics at the University of Washington, states that the falling fertility rate also represents a success, thanks to more access to contraception and more women in education and work.

Another global phenomenon: gender wage gap

According to several studies, another global issue has an impact on the declining birth rate in many countries: the inequality faced by women and, consequently, gender wage gap. This phenomenon is undoubtedly worldwide: a UN report states that women only make 77 cents for every dollar men earn.

Gender pay disparities are caused by multiple factors: sectoral segregation, where men and women are concentrated in different fields or roles, is significant.

Additionally, the unequal division of paid and unpaid work, along with the existence of the glass ceiling, perpetuates this gap. The glass ceiling limits women's advancement to top positions, while the burden of caregiving, predominantly sustained by women, further disadvantages them in the workforce due to the unequal distribution of unpaid domestic labour.

OECD reports that the unadjusted gender pay gap stands at 11.9%. This gap varies widely across countries, ranging from 1.2% in Belgium to 31.1% in Korea.

This leads to an interesting argument: if in a family only one parent can continue working while the other needs to take care of the child, it will most likely be the one who gets paid more rather than the other way around. In most cases, women are paid less even while working in the same position.

Therefore, gender pay gap actively affects a woman’s possibility to return to work or to continue working, forcing her to face the harsh reality of having to rely on the other person in the couple.

Finding a possible solution in equality

Some governments offered financial contributions to encourage citizens to have children, such as enhanced parental leave, free childcare, and extra employment rights, but there is no clear answer on how to resolve this phenomenon.

One of the possible solutions, both to help the birth rate and to improve women’s equality, would be to act on these imbalances between men and women when starting a family.

The obstacles women face in general might be reflected in this drop in births, as people – women included – are constantly motivated toward developing a career, and having to decide between a career and a family is not an easy task.

It’s no wonder many Korean women – as stated in the BBC interviews – are unwilling to put aside their dreams, one way or another. One of the women interviewed states, “We are the first generation who get to choose. Before it was a given, we had to have children. And so, we choose not to because we can.”

This is an issue not only for South Korean women but also for most women worldwide. Working on these obstacles and unfair conditions might not necessarily increase the birth rate immediately or significantly; however, it might make it easier to choose between career and family or, ideally, completely remove the need for a choice.

References

Birth rate

- https://www.ft.com/content/008a1341-1882-4b98-83d4-0d7dc08a4134

- https://www.ft.com/content/444a637b-9712-475b-8c14-9b147f4ff244

- https://time.com/6835865/south-korea-fertility-rate-2023-record-low/

- Why South Korean women aren't having babies (bbc.com)

- https://www.unfpa.org/swp2023/too-few

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/birth-rate-by-country

- https://www.bbc.com/news/health-53409521

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/global-decline-of-fertility-rates-visualised/

- https://www.ilpost.it/2024/02/28/corea-sud-crisi-demografica/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/28/fears-for-future-as-south-koreas-fertility-rate-drops-again

- https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/04/113_367888.html

- https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2024/02/113_350152.html

- https://www.instagram.com/p/C4z1PwJsB_z/?igsh=MXZoY242NWc0eWc4bA==

- https://www.prb.org/resources/did-south-koreas-population-policy-work-too-well/

- https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-14722-4

Gender wage gap

- https://interactive.unwomen.org/multimedia/infographic/changingworldofwork/en/index.html

- https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20240303050146

- https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www2/common/viewpage.asp?newsIdx=370268&categoryCode=602

- https://ourworldindata.org/economic-inequality-by-gender

Feminism and politics

- https://www.asiapacific.ca/publication/south-korea-election-watch-2022-part-three

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-60643446

- https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/08/asia/south-korea-election-young-people-intl-hnk-dst/index.html

- https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/590977

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14680777.2017.1283343