Class dismissed: the end of a new chance after prison?

Students at the university penitentiary hub inside Dozza Prison will no longer have access to the physical spaces they have used until now. Two former Dozza students share their thoughts about it.

Pubblicato il 27 giugno 2025 | Diritto e Diritti

Di Arianna Albertazzi, Margherita Cavicchioni, Sofia Mundo.

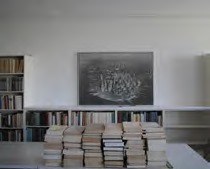

Books inside Dozza penitentiary. Source: Repertorio di immagini degli spazi trattamentali delle carceri in Emilia-Romagna

A quiet wing in a loud prison

There was once a place inside Dozza penitentiary where silence meant focus, not fear. Wing 1D, which used to host two groups: the inmates who played rugby for Giallo Dozza, the sportive society born inside the penitentiary, and the inmates enrolled in the University of Bologna (Unibo) through the Penitentiary University Hub (P.U.P., Polo Universitario Penitenziario).

The project started in 2015, through a partnership between the Dozza and the University of Bologna to give inmates access to higher education. Upon request, students could move in wing 1D, where the single cells, the shared study spaces, and the library made it easier for them to pursue their academic goals.

Wing 1D became the heart of the P.U.P., a place where a new community grew, out of necessity. Until a couple of months ago, when the Ministry of Justice decided to allocate 50 difficult juvenile detainees from all Italy inside the Dozza, without any previous notice.

Since the prison was already overcrowded, it was necessary to reallocate various sections and temporarily dismantle the P.U.P.’s room.

Today, even though the project is still active, the former P.U.P. classrooms can no longer be used. Desks have been removed, and public computers are collecting dust. The dismantling of the study space should be temporary. Or at least, that’s what the administration said. But there is no indication of when the situation will go back to normal — in Italy, “temporary” could mean two months or two years. In the meantime, students are now left with fewer points of reference, and guidance has become scarce.

The origins of Penitentiary University Hubs

Penitentiary university hubs began in Italy in the 1980s, when some inmates – mainly imprisoned for political crimes — demanded access to university education. Pilot programs in Padua and Turin paved the way for collaboration between universities and the Ministry of Justice, eventually leading to a system where inmates who met academic requirements could enrol as university students.

Unibo’s P.U.P. began in 2015 when the then-Rector of the University of Bologna, professor Ivano Dionigi appointed a dedicated figure to oversee it: the Rector’s Delegate for the Right to Education of Incarcerated and Liberty-Deprived Individuals. The first Rector’s delegate, professor Giorgio Basevi, needed the help of experts in order to get the P.U.P. started. This is why he personally contacted Professor Susanna Vezzadini, a scholar known for her work on restorative justice. Her involvement helped ensure the program was not just about access to education, but about redefining prison culture.

A System in Crisis

The dismantling of the P.U.P., even if temporary, is only one part of a broader picture in which the prison system is treated as a crisis to be managed, rather than a structural issue to be addressed. Two critical challenges continue to plague Italy’s prison system: overcrowding and a high rate of suicides.

Data from the Antigone show that the Italian prison occupancy rate in 2024 stood at 132.6%. At Dozza, it was 170.8%, more than 40 percentage points above the national average. Equally concerning is the number of suicides. According to the Garante Nazionale per i diritti delle Persone private della Libertà personale (GNPL), 88 inmates died by suicide inside Italian prisons in 2024. By April 2025, an additional 25 have already taken their lives.

The Bologna chapter: the experience of Professor Vezzadini

Professor Susanna Vezzadini teaches Sociology of Law and Deviance at the University of Bologna, and her research has always been centered around reparative justice and victimology. That’s why her role was pivotal in the creation of the hub in Bologna. As a professor, she taught and examined many P.U.P. students.

Speaking about her experience in the program, Professor Vezzadini said that it was not only an enrichment of professional skills but also of human values, like human connection, freedom of speech, respect, human dignity and social vulnerability. As she told us, these values and the P.U.P. require work to keep them alive.

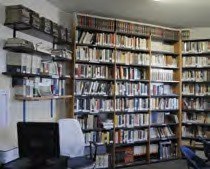

The library inside Dozza penitentiary. Source: Repertorio di immagini degli spazi trattamentali delle carceri in Emilia-Romagna

Freedom of studying

S. began his undergraduate studies in prison and finished his master’s degree outside of the walls of Dozza. He is an avid reader and likes talking about Proust and Joyce, Dostoevsky and the torments of Raskòl'nikov. In Italian prisons, the level of literacy among inmates is still very low, and people like S. are a precious resource for their peers – particularly in a system where even a highlighter must be asked through a written request, also known among inmates as domandina.

As any other university student, S. would go to the Dozza library every morning to study. His study sessions were only interrupted by the lunch break and usually ended around 5 p.m. Students like him in 1D were granted permission to have a laptop in their rooms —with no internet access– to work on their papers. Otherwise, they had to wait for their turn to use the shared computer in the P.U.P. room.

S. describes his days in 1D as quiet, not boring. He talks with great affection about the strong sense of community among inmates. If there was something to discuss, they would arrange a wing meeting to solve any issues that arose. On Saturday, the usual day of the rugby match, P.U.P. students asked permission to cheer for their peers. Supporting one another led the inmates of 1D to build their own community. This helped many to cope with prison life.

Some are Already Saved

S. considered his time at the Dozza as a “fracture” in his life —a very painful one. However, he knew that once out, he would go back to his normal life. S. also adds: “Those who manage to save themselves are already, in some way, saved before. They have families, friends, an identity built outside of prison walls. Once free, it is very unlikely they’d be back at Dozza. Many others, however, see their time in prison as a holiday between one robbery and the next.” These are the ones that are likely not to make it outside, those who may end up going back—unless they are offered an alternative: the chance to begin a different life path, whether through sport, a job or studying. This is why programs like the P.U.P. are necessary inside a reality like the Dozza.

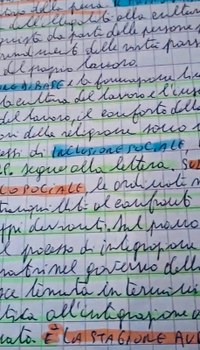

A photo of L.’s notes.

L., the Law Student and Sunday Chef

L. is another former P.U.P. student. He claims to be an excellent cook and that his pasta al forno is absolutely the best. His culinary talent made him famous inside Wing 1D, so every Sunday he would prepare lunch for everybody.

When he became a student, his goal was to become an HR consultant, but he later became passionate about Law. He says it was the tutors who helped him discover this new path. Tutors, who play a pivotal role at the P.U.P., are university students who volunteer to support their peers inside Dozza in preparing for exams.

But of course, a proper study session isn’t complete without a coffee break. That’s when students and tutors got to chat and bond, between one page and the other. Thanks to these conversations, L. decided to change course and pursue a Law degree. His favourite class was Penitentiary System, while he did not find Commercial Law as compelling.

L. has always worked, even when he started studying at the P.U.P. He said that he could not sleep much, so he used to wake up at 4 a.m. to prepare for the exams, and then start his work shift inside the Dozza at 9. Now he is out, and he has six exams left to graduate. However, being a working student is not easy, and finding time to study is challenging. He said that his Tax Law manual is on his desk, catching dust.

When he was in 1D, he had to submit a request to th professor at least one month in advance to take an exam. Assessment took place in the meeting room inside the Dozza. When asked if he got nervous before an exam, L. answered in a way that all students can relate to: the night before the exams, he could never sleep because he kept reviewing his notes in his head.

A culture of study destroyed?

The experiences of S. and L., along with the account of Professor Vezzadini, help us understand the importance of education programs in the rehabilitation process of an inmate.

In prison, even the smallest sense of community or normality becomes a form of escape. “Overcrowding is terrible,” says L. “it takes away any chance for leisure, for connection. You start losing tolerance for your cellmates. But when someone is given the opportunity to study, their attitude changes. It helps them grow. In wing 1D, we never fought.”

S. shares the same sentiment, stressing that not having a space dedicated to P.U.P. is not only a loss of educational opportunity but a cultural regression. “Culture is always seen as dangerous, because it leads to questions, which lead to doubt, which leads to research—and eventually, to knowledge,” he says. In today’s political climate, culture is more necessary than ever as a counterweight to ideology.

“The point is, if your mindset is ideological, you cannot truly embrace culture—they are fundamentally incompatible. Culture teaches us to leave our own shore, to question ourselves, and to seek out the other. How do we truly meet one another? Only by letting go of the ideology of ‘I am who I am.’ If each of us takes a step forward, maybe we’ll meet halfway. Culture is central—and that’s precisely why it’s feared,” S. concludes.

Professor Vezzadini’s idea of freedom echoes this sense of culture. According to her, freedom is being able to look at the world with your own eyes— and knowing that your view matters. The temporary repurpose of the P.U.P. space signifies the disappearance of a rare human experience—one that allowed incarcerated individuals to see the world anew, and perhaps, at last, to see themselves differently.

S., L., and Professor Vezzadini all share the same fear: it took years to create a “culture of study” inside the walls of Dozza, but shutting it down required only a moment—as is often the case with anything good that happens in prison. Will things ever go back to how they were? Right now, the P.U.P. as they knew it is gone, perhaps for good.

References

-

Associazione Antigone. (2024). Report di fine anno 2024. Associazione Antigone.

-

Cavalieri, R. (a cura di). (2023). Repertorio di immagini degli spazi trattamentali delle carceri in Emilia-Romagna. Regione Emilia-Romagna, Garante delle persone sottoposte a misure restrittive o limitative della libertà personale. Fotografie di Francesco Cocco.

-

Suriano, G. (a cura di). (2025, 6 maggio). Focus suicidi e decessi in carcere anno 2025. Osservatorio penitenziario GNPL. Dipartimento dell’Amministrazione Penitenziaria (DAP).

-

www.antigone.it (Casa Circondariale di Bologna “Dozza”) [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]

-

www.corriere.it/ (Giovani e carcere, depredare l'Ucraina, l'Europa e Big Tech, la pandemia rimossa, orrori houthi) [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]

-

www.ristretti.org/ (Bologna. Lo strano caso del ghetto in carcere per giovani stranieri e il Polo universitario smantellato) [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]

-

www.unibo.it Giorgio Basevi [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]

-

www.unibo.it Ivano Dionigi [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]

-

www.unibo.it Susanna Vezzadini [ultima data di consultazione: 24 maggio 2025]